Before one could land on the Moon, one needed to learn more about it.

Before one could land on the Moon, one needed to learn more about it.

What was the surface made of? What was the terrain like? Where would we land? The Ranger missions hoped to assist in answering all of these questions.

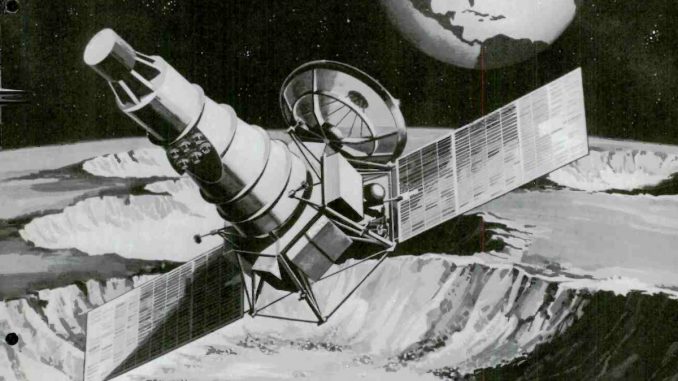

But while it should be relatively simple to send a spacecraft to snap photos of the Moon, how would you get them back?

The answer was to not take photographs at all.

But before resolving the photography question, NASA first had to get a probe to the Moon – which turned out to be more difficult than previously thought. A number of attempts made during the Pioneer space probe program of the late 1950s ended in various – and at times catastrophic – failures. Spurred on by the success of the Soviet’s Luna 1 lunar probe earlier that year, in March 1959 the Pioneer 4 mission finally managed to escape Earth’s gravity and make a lunar flyby – while it didn’t return any images, it did transmit back radiation data, and proved the viability of deep space radio communications and the ability to track spacecraft.

Pioneer 4’s success helped to embolden the Americans in their aspirations for a manned lunar mission, in part to get one up on the Soviets. But they would need to get more information about lunar conditions before sending people there. Which would mean more probes.

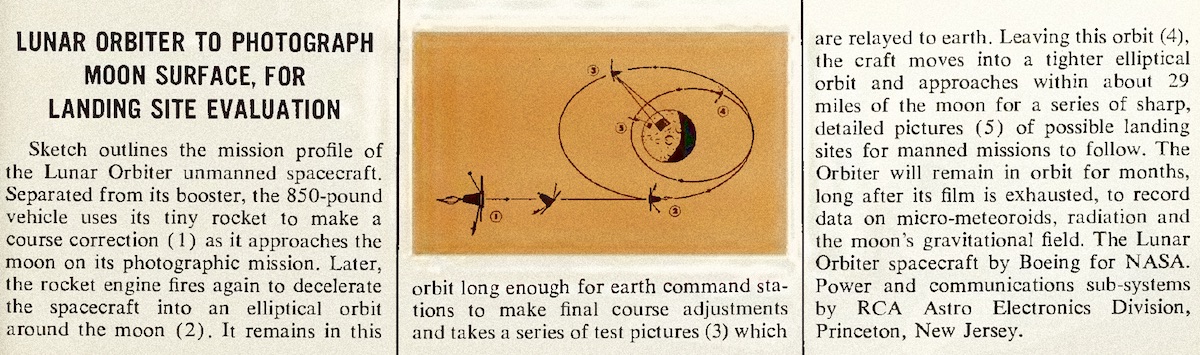

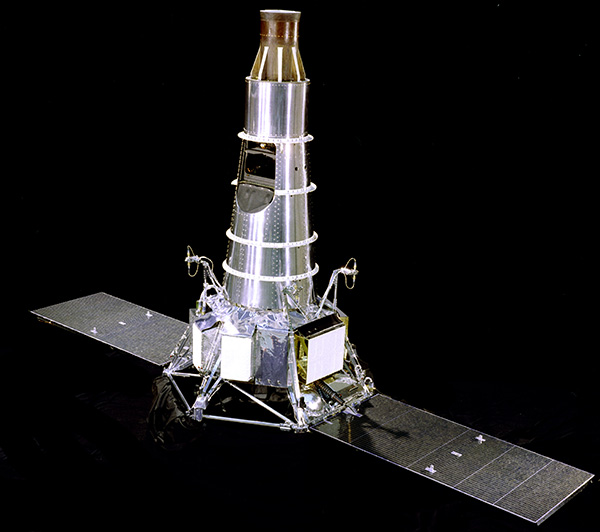

After the Soviet Luna 3 probe took pictures of the dark side of the Moon and radioed them back to Earth, in late 1959 the Ranger program was established to send probes the the Moon with the intent of acquiring further both scientific data and imagery. But the success of Pioneer 4 turned out to have been a bit of beginners’ luck.

Perhaps due to corner-cutting in NASA’s frantic quest to land humans on the Moon before the Soviets, the first six Ranger missions failed. Problems with the launch vehicle left Rangers 1 and 2 in short-lived low-Earth orbits. Rangers 3, 4 and 5 missed the Moon, suffered equipment failures and missed the Moon again, respectively.

The program’s early expensive failures earned it the derisive nickname ‘shoot and hope’, and the US Congress launched an investigation into ‘problems of management’ at NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) – not the kind of launch NASA preferred.

Just before the launch of Ranger 6 it was discovered that gold plated on to elements inside a type of diode used in the Rangers’ circuits could flake off and float about in zero gravity, shorting out the diodes. It took three months to replace the diodes and retest the probe, but while Ranger 6 made it to the Moon, a charge of static electricity picked up in the Earth’s atmosphere damaged the circuitry responsible for switching on the video cameras. Congress was furious and held more investigations.

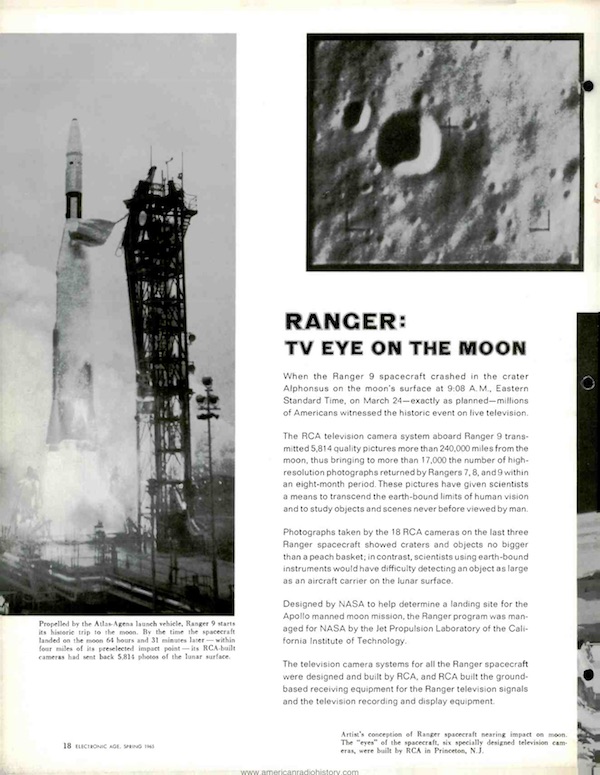

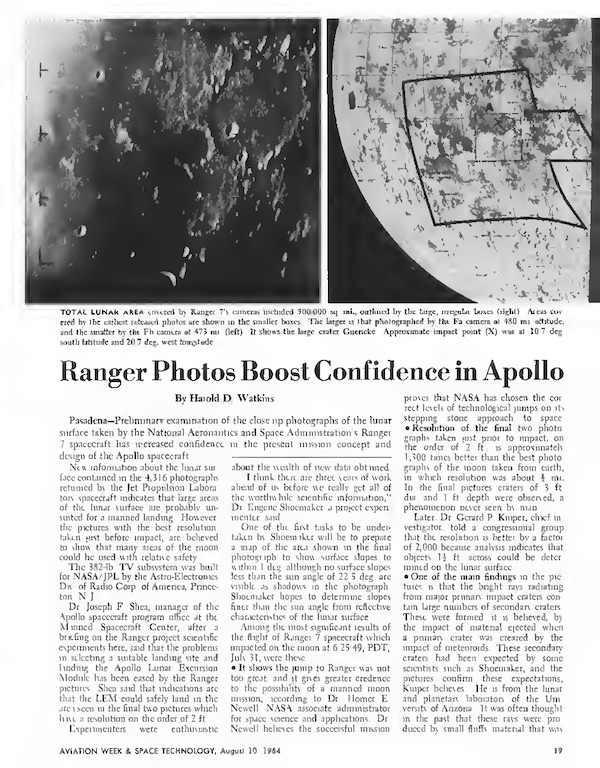

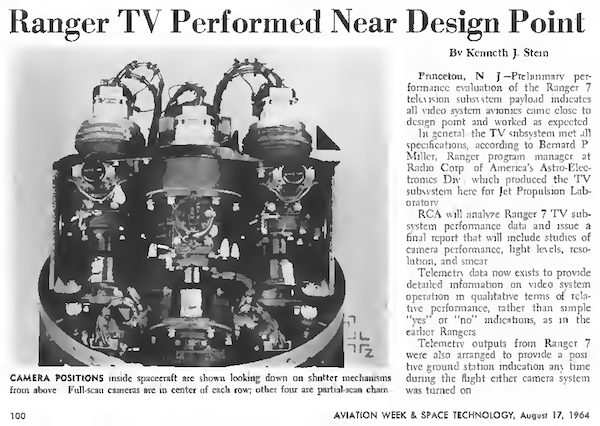

But finally, Ranger 7, launched on the 28th of July, 1964, both made it to the Moon and returned video images, to the great joy of those involved. After the misery of six failures, NASA engineers finally had confirmation their design of Apollo’s landing gear was prudent, and lunar scientists were able to confidently determine the substance and makeup of the Moon’s surface.

The Rangers made Apollo possible.

Be the first to comment