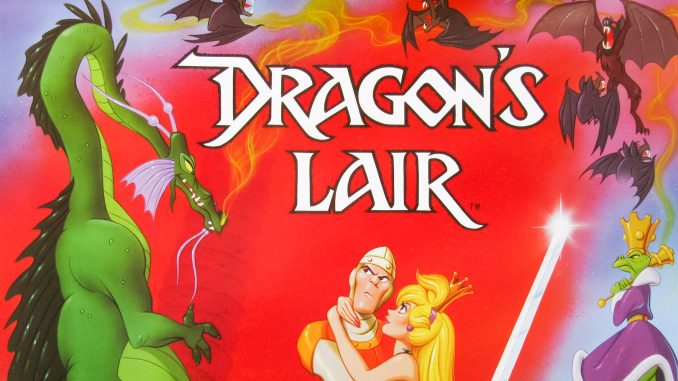

When animator Don Bluth agreed to animate an obscure laserdisc videogame tentatively titled “The Dragon’s Lair”, little did he know it would become one of his biggest successes…

Dragon’s Lair… Dragon’s Lair… ah yes Dragon’s Lair.

I remember that castle fantasy arcade game, the one that by 1986 when I first laid my eyes on it (in Australia), was always in the corner by itself and not many people playing it because it was more expensive than the 20c Galaga, Spy Hunter or Gyruss. Little did I know of the incredible story behind how Dragon’s Lair came to be. As a young teenager playing arcade games, I only marvelled at its amazing graphics but also baulked at playing it because of the high price per game. It was inherently different from every other arcade game in every possible way at the time of it’s release way back in 1983. Unlike every other pixelated sprite styled video game in the arcades, Dragon’s Lair has a most fascinating history to uncover, it became an instantly famous arcade game in America due to its unique cartoon animated graphics as well as its intriguing but frustrating gameplay. Still to this very day, Dragon’s Lair and its animated movie gameplay by Don Bluth are highly regarded in the history of video gaming. Its graphical style ventured into uncharted waters in a video gaming era where no one had ever seen or attempted to make an animated cartoon arcade game before. This the story of Dragon’s Lair and the person behind its animation, Don Bluth, of how it all came to be.

I remember that castle fantasy arcade game, the one that by 1986 when I first laid my eyes on it (in Australia), was always in the corner by itself and not many people playing it because it was more expensive than the 20c Galaga, Spy Hunter or Gyruss. Little did I know of the incredible story behind how Dragon’s Lair came to be. As a young teenager playing arcade games, I only marvelled at its amazing graphics but also baulked at playing it because of the high price per game. It was inherently different from every other arcade game in every possible way at the time of it’s release way back in 1983. Unlike every other pixelated sprite styled video game in the arcades, Dragon’s Lair has a most fascinating history to uncover, it became an instantly famous arcade game in America due to its unique cartoon animated graphics as well as its intriguing but frustrating gameplay. Still to this very day, Dragon’s Lair and its animated movie gameplay by Don Bluth are highly regarded in the history of video gaming. Its graphical style ventured into uncharted waters in a video gaming era where no one had ever seen or attempted to make an animated cartoon arcade game before. This the story of Dragon’s Lair and the person behind its animation, Don Bluth, of how it all came to be.

For me it was strange to see an animated game in the arcades and stranger still that it was not put together by a known arcade coder, developer or distributor. A pimply faced teen who was playing the latest arcade games the likes of Out Run, Yie Ar Kung Fu and Space Harrier (I was brought up on Konami, Sega and Atari arcade gaming), I was completely unaware that Dragon’s Lair had been a major arcade gaming success upon its release, even being hailed as the saviour to the now infamous and highly reported 1983 video gaming industry meltdown. In arcades across the United States, during 1983, Dragon’s Lair had people queuing up outside the door just to play it. In a time when arcade video gaming was ruled by the likes of Frogger, Pac Man, Space Invaders and Pit Stop – Dragon’s Lair created gaming history, it was dare I say it, quite a video gaming phenomenon, as game players looked in astonishment at its amazing movie animated graphical display.

For me it was strange to see an animated game in the arcades and stranger still that it was not put together by a known arcade coder, developer or distributor. A pimply faced teen who was playing the latest arcade games the likes of Out Run, Yie Ar Kung Fu and Space Harrier (I was brought up on Konami, Sega and Atari arcade gaming), I was completely unaware that Dragon’s Lair had been a major arcade gaming success upon its release, even being hailed as the saviour to the now infamous and highly reported 1983 video gaming industry meltdown. In arcades across the United States, during 1983, Dragon’s Lair had people queuing up outside the door just to play it. In a time when arcade video gaming was ruled by the likes of Frogger, Pac Man, Space Invaders and Pit Stop – Dragon’s Lair created gaming history, it was dare I say it, quite a video gaming phenomenon, as game players looked in astonishment at its amazing movie animated graphical display.

As the first game at 50c per play it did not deter gamers, Newsweek captures the level of excitement displayed over the game stating “Dragon’s Lair is this summer’s hottest new toy: the first arcade game in the United States with a movie-quality image to go along with the action. The game has been devouring kids’ coins at top speed since it appeared early in July. People waited all day in the crush at Castle Park without getting to play, It’s the most awesome game I’ve ever seen in my life.” By the end of 1983, Electronic Games and Electronic Fun were rating Dragon’s Lair as the number one video arcade game in the USA, it received recognition as the most influential game of 1983, as regular computer graphics looked “rather elementary compared to Don Bluth’s top-quality animation”. By February of 1984, it was reported to have grossed over $32 million for arcade game distributor / publisher, Cinematronics.

Don Bluth wasn’t an arcade game household name, so who was he exactly? Don had plied his trade as a film animator, film director, producer, writer and production designer. As a young child from El Paso,Texas, in the 1940’s, he would ride his horse to the town movie theater to watch Disney films and is quoted as saying “then I’d go home and copy every Disney comic book I could find”. In the 1950’s he gained employment at Disney as an assistant but left soon after and in the late 1960’s he joined Filmation, working on layouts for The Archies. In the 1970’s he found himself again at Disney working on cartoons such as Robin Hood, Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too, The Rescuers and directing animation on Pete’s Dragon. Then after he and about 11 other animators walked out of Disney in the late 1970’s, he ventured on his own, forming his own company as an independent production business. He is most noted for teaming up with Steven Spielberg in the 1980’s, making mega animated movie hits such as An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988). So how did Don Bluth end up with animation credits for arcade video games, Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace?

Don Bluth wasn’t an arcade game household name, so who was he exactly? Don had plied his trade as a film animator, film director, producer, writer and production designer. As a young child from El Paso,Texas, in the 1940’s, he would ride his horse to the town movie theater to watch Disney films and is quoted as saying “then I’d go home and copy every Disney comic book I could find”. In the 1950’s he gained employment at Disney as an assistant but left soon after and in the late 1960’s he joined Filmation, working on layouts for The Archies. In the 1970’s he found himself again at Disney working on cartoons such as Robin Hood, Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too, The Rescuers and directing animation on Pete’s Dragon. Then after he and about 11 other animators walked out of Disney in the late 1970’s, he ventured on his own, forming his own company as an independent production business. He is most noted for teaming up with Steven Spielberg in the 1980’s, making mega animated movie hits such as An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988). So how did Don Bluth end up with animation credits for arcade video games, Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace?

First, let’s take a quick look at the technology behind the games themselves. While every other arcade game had microchips on a board, Dragon’s Lair, published by Cinematronics in 1983 was primarily powered by a few rom chips and at the heart of the machine and the game was a Pioneer, Laserdisc, (model PR7820 and other Pioneer models after that). Technically it was far superior and ahead of its time, but not an acceptable or a well known format that the average arcade gaming punter may have realised was inside the arcade machine they were playing. How did this all play out you ask?

First, let’s take a quick look at the technology behind the games themselves. While every other arcade game had microchips on a board, Dragon’s Lair, published by Cinematronics in 1983 was primarily powered by a few rom chips and at the heart of the machine and the game was a Pioneer, Laserdisc, (model PR7820 and other Pioneer models after that). Technically it was far superior and ahead of its time, but not an acceptable or a well known format that the average arcade gaming punter may have realised was inside the arcade machine they were playing. How did this all play out you ask?

You have to go back to 1958 when Optical Video Recording technology, using a transparent disc, was invented by David Paul Gregg and James Russell. The technology was patented in 1961 and from there MCA bought the patents. In 1969, the Philips company developed a videodisc with a reflective mode having advantages over MCA’s transparent disc, so MCA and Philips combined their efforts and first publicly demonstrated the video disc in 1972. In 1978 the analogue LaserDisc was first available commercially in Atlanta, Georgia, showcasing movies like Jaws, two years after the introduction of the VHS VCR, and four years before the introduction of the CD (which is based on laser disc technology). Pioneer Electronics later purchased the majority stake in the Laserdisc format and that’s why there’s a Pioneer Laserdisc powering Dragon’s Lair as well as the Space Ace arcade video games (and possibly most other arcade LaserDisc games).

You have to go back to 1958 when Optical Video Recording technology, using a transparent disc, was invented by David Paul Gregg and James Russell. The technology was patented in 1961 and from there MCA bought the patents. In 1969, the Philips company developed a videodisc with a reflective mode having advantages over MCA’s transparent disc, so MCA and Philips combined their efforts and first publicly demonstrated the video disc in 1972. In 1978 the analogue LaserDisc was first available commercially in Atlanta, Georgia, showcasing movies like Jaws, two years after the introduction of the VHS VCR, and four years before the introduction of the CD (which is based on laser disc technology). Pioneer Electronics later purchased the majority stake in the Laserdisc format and that’s why there’s a Pioneer Laserdisc powering Dragon’s Lair as well as the Space Ace arcade video games (and possibly most other arcade LaserDisc games).

Arcade gaming up until 1983 had essentially been limited to pretty standard hardware capabilities. Coders and graphical artists were severely restricted in what they could portray on a video arcade game screen. According to my research in 1983, the very first LaserDisc video game was Sega’s, shoot ‘em up, called Astron Belt but it had very little fanfare or is given the credit as being the first ever laserdisc arcade game. As history has shown, later that same year, laserdisc arcade gaming was taken by storm as Dragon’s Lair was released, capable of better audio, better graphics, better resolution and able to store as well as access game information directly from a huge sized 20 centimetre disc. The main disadvantages to Laserdisc gaming was that gameplay was often harder with the playing control mechanism used was often very frustrating in comparison to existing arcade games. The laserdisc players while of high quality were not designed for the long use of arcade gaming in mind, there would often be momentary lags of a few seconds while playing the game as the laser disc was being read and the life of the the actual Laser Disc machine was limited and could fail quite easily often requiring costly repairs or replacement.

Arcade gaming up until 1983 had essentially been limited to pretty standard hardware capabilities. Coders and graphical artists were severely restricted in what they could portray on a video arcade game screen. According to my research in 1983, the very first LaserDisc video game was Sega’s, shoot ‘em up, called Astron Belt but it had very little fanfare or is given the credit as being the first ever laserdisc arcade game. As history has shown, later that same year, laserdisc arcade gaming was taken by storm as Dragon’s Lair was released, capable of better audio, better graphics, better resolution and able to store as well as access game information directly from a huge sized 20 centimetre disc. The main disadvantages to Laserdisc gaming was that gameplay was often harder with the playing control mechanism used was often very frustrating in comparison to existing arcade games. The laserdisc players while of high quality were not designed for the long use of arcade gaming in mind, there would often be momentary lags of a few seconds while playing the game as the laser disc was being read and the life of the the actual Laser Disc machine was limited and could fail quite easily often requiring costly repairs or replacement.

Where Don Bluth came in as animator of Dragon’s Lair and later Space Ace, was as one would say “a bit out of left field”. Rick Dyer, the then President of Advanced Microcomputer Systems, had failed to get his so called ‘Fantasy Machine’ invention off the ground, it was unfortunately a spectacular failure, however it did demonstrate that still images and narration could be stored and accessed from a video disc with a graphic adventure game he had devised, called, The Secrets of the Lost Woods. After having watched a Don Bluth animated movie – The Secret of Nimh, Rick Dyer realized he needed 2D animation, an action script and sounds to bring excitement to his game which would lead to the development of Dragon’s Lair. Originally he had created Dragon’s Lair for home computers but he had no way of marketing his idea onto the home computer and console market. So he contacted Don Bluth to make his animated gamed dream a reality.

Where Don Bluth came in as animator of Dragon’s Lair and later Space Ace, was as one would say “a bit out of left field”. Rick Dyer, the then President of Advanced Microcomputer Systems, had failed to get his so called ‘Fantasy Machine’ invention off the ground, it was unfortunately a spectacular failure, however it did demonstrate that still images and narration could be stored and accessed from a video disc with a graphic adventure game he had devised, called, The Secrets of the Lost Woods. After having watched a Don Bluth animated movie – The Secret of Nimh, Rick Dyer realized he needed 2D animation, an action script and sounds to bring excitement to his game which would lead to the development of Dragon’s Lair. Originally he had created Dragon’s Lair for home computers but he had no way of marketing his idea onto the home computer and console market. So he contacted Don Bluth to make his animated gamed dream a reality.

In an interview from the 1980’s (found on Youtube), Don Bluth explains the project synopsis and design of how the concept of Dragons Lair was envisaged “first of all you have to give the illusion that the game player is in control when indeed he may not be, but you must give that illusion, I thought wow that’s right up our alley thats movie making. Give the illusion, present a moment to him in which he must react to a moment of danger and then get him to react to that moment at the right moment and then we’ll see another scene which he is saved from that, I thought that’s very interesting how can I design a game which will present enough of those moments in short little periods of time to where the game becomes exciting, that was the challenge of the game”.

As an independent entity, and on a shoestring budget of US$1 million, when Don Bluth and his studio took up the animation of arcade game Dragon’s Lair, seven months later it was finished. An astonishing feat considering the amount of work involved. Statistically speaking, 13 animators were required to sketch 50,000 drawings of game characters in action. 24 drawings required for each second on screen. Drawings were transferred onto plastic sheets otherwise called cells and had to then be painted which also included drawing and painting of the backgrounds. Special effects such as raging fires, crumbling walls and deadly vapours had to be drawn and painted and were included in the game as danger signals to the player. All of the cells were combined and photographed one frame at a time. 1440 frames for each minute of completed scenes. Dialogue, sound effects and a musical score were then added before it was all transferred and stored onto a Laserdisc as the finished animated movie game.

As an independent entity, and on a shoestring budget of US$1 million, when Don Bluth and his studio took up the animation of arcade game Dragon’s Lair, seven months later it was finished. An astonishing feat considering the amount of work involved. Statistically speaking, 13 animators were required to sketch 50,000 drawings of game characters in action. 24 drawings required for each second on screen. Drawings were transferred onto plastic sheets otherwise called cells and had to then be painted which also included drawing and painting of the backgrounds. Special effects such as raging fires, crumbling walls and deadly vapours had to be drawn and painted and were included in the game as danger signals to the player. All of the cells were combined and photographed one frame at a time. 1440 frames for each minute of completed scenes. Dialogue, sound effects and a musical score were then added before it was all transferred and stored onto a Laserdisc as the finished animated movie game.

Not being a global corporate conglomerate like Disney, Don Bluth’s production couldn’t afford to hire any models, or professional actors so the animators used photos from Playboy magazines for inspiration to draw the character Princess Daphne. They also used their own voices for all the Dragon’s Lair characters, to reduce costs. One professional voice actor does feature – Michael Rye, as the narrator in the attract sequence, he is also the narrator for Space Ace and Dragon’s Lair II.

Not being a global corporate conglomerate like Disney, Don Bluth’s production couldn’t afford to hire any models, or professional actors so the animators used photos from Playboy magazines for inspiration to draw the character Princess Daphne. They also used their own voices for all the Dragon’s Lair characters, to reduce costs. One professional voice actor does feature – Michael Rye, as the narrator in the attract sequence, he is also the narrator for Space Ace and Dragon’s Lair II.

The voice of Princess Daphne was portrayed by Vera Lanpher, who was head of the Clean-up Department at the time. Dirk, the main characters voice belongs to film editor Dan Molina, (who later went on to perform the bubbling sound effects for another animated character, Fish Out of Water, from 2005’s Disney film Chicken Little).

The voice of Princess Daphne was portrayed by Vera Lanpher, who was head of the Clean-up Department at the time. Dirk, the main characters voice belongs to film editor Dan Molina, (who later went on to perform the bubbling sound effects for another animated character, Fish Out of Water, from 2005’s Disney film Chicken Little).

The original Dragon’s Lair, USA 1983, arcade game cabinets used a single side NTSC laserdisc, on the other side of the disc it was metal backed to prevent bending. European versions of the game were manufactured by Atari under license and used a single side PAL disc manufactured by Philips (not metal backed). Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace arcade games in Europe were different in cabinet design to that of the Cinematronics version in the USA. A LED digital scoring panel was replaced with an on screen scoring display appearing after each level and the Atari branding was present in various places over the machine. It also came with the cone LED player start button not seen on the USA cabinets.

While the cartoon animation stored on Laser Disc was arcade gaming eye candy, the concept and gameplay meant you actually had the power of decision making. Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace games, are also known as the first true interactive arcade games, back then they called it “participatory video entertainment”. In Dragon’s Lair, you do not control Dirk, rather you direct him in what to do. The player decides to make a correct or incorrect move with the joystick which would determine the outcome of the game. This was done by areas on the laserdisc being accessed according to which joystick control command was given. The game has 38 to 42 different episodes with over 1,000 life-and-death situations and over 200 different decisions to make. It has been confirmed from a video taped game that it only takes about 12 minutes to complete the game if you know all the moves.

While the cartoon animation stored on Laser Disc was arcade gaming eye candy, the concept and gameplay meant you actually had the power of decision making. Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace games, are also known as the first true interactive arcade games, back then they called it “participatory video entertainment”. In Dragon’s Lair, you do not control Dirk, rather you direct him in what to do. The player decides to make a correct or incorrect move with the joystick which would determine the outcome of the game. This was done by areas on the laserdisc being accessed according to which joystick control command was given. The game has 38 to 42 different episodes with over 1,000 life-and-death situations and over 200 different decisions to make. It has been confirmed from a video taped game that it only takes about 12 minutes to complete the game if you know all the moves.

The object of Dragons Lair was that old plot of saving the damsel in distress. You played Dirk the Daring knight who had to reach The Dragon’s Lair inside a vast castle, slay Singe the dragon and rescue Daphne, the Princess. Once you complete the task, the game, the quest and the story are all over because there are no higher levels of difficulty. Basically, there is really no reason to obtain a high score, even though points are scored based on how far you can get and how well you can do.

The object of Dragons Lair was that old plot of saving the damsel in distress. You played Dirk the Daring knight who had to reach The Dragon’s Lair inside a vast castle, slay Singe the dragon and rescue Daphne, the Princess. Once you complete the task, the game, the quest and the story are all over because there are no higher levels of difficulty. Basically, there is really no reason to obtain a high score, even though points are scored based on how far you can get and how well you can do.

Contrary to popular belief, both Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace did contain diagonal movements. In some cases, these movements were simply the combination of two acceptable moves, while in other cases the diagonal move was distinct (for example, during the whirlpool segment, moving to the right or left is acceptable, moving diagonal up-right or up-left is acceptable, but simply moving up results in death). In all cases, the diagonal moves were optional, and there was always a 4-way alternative. Because of the Laser Disc format, movement during the game had to happen in a split-second. The game jumped between scenes depending on the success or failure of the player. It was an impressive feat for the time, but made for frustrating gameplay.

Contrary to popular belief, both Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace did contain diagonal movements. In some cases, these movements were simply the combination of two acceptable moves, while in other cases the diagonal move was distinct (for example, during the whirlpool segment, moving to the right or left is acceptable, moving diagonal up-right or up-left is acceptable, but simply moving up results in death). In all cases, the diagonal moves were optional, and there was always a 4-way alternative. Because of the Laser Disc format, movement during the game had to happen in a split-second. The game jumped between scenes depending on the success or failure of the player. It was an impressive feat for the time, but made for frustrating gameplay.

Between the USA and European versions certain scenes were not shown or played, including the drawbridge, the “Ye Boulders” sign before the rapids, and the scene after the battle against the Knight. European release of Dragon’s Lair showed all the scenes played in the order they are stored on the laserdisc, and the game started on the drawbridge scene but that was cut from the North American version.

Due to the success of Dragon’s Lair, Don Bluth and Rick Dyer teamed up again releasing Space Ace. It too used the laserdisc technology and animated cartoon story like gameplay and was found in arcades just 4 months later. Once again the player was required to move the joystick or press the fire button at key moments in the animated sequences to govern the hero’s actions. However, the game’s action was more varied with the player occasionally given the temporary option to either have the character he is controlling transform back into his adult form, or remain as a boy with different styles of challenges. Like Dragon’s Lair, Space Ace is composed of numerous individual scenes, which require the player to move the joystick in the right direction or press the fire button at the right moment to avoid the various hazards that hero Dexter / Ace faces. Space Ace introduced a few gameplay enhancements, most notably selectable skill levels and multiple paths through several of the scenes. At the start of the game the player could select one of three skill levels; “Cadet”, “Captain” or “Space Ace” for easy, medium and hard respectively; only by choosing the toughest skill level could the player see all the sequences in the game (only around half the scenes are played on the easiest setting).

Due to the success of Dragon’s Lair, Don Bluth and Rick Dyer teamed up again releasing Space Ace. It too used the laserdisc technology and animated cartoon story like gameplay and was found in arcades just 4 months later. Once again the player was required to move the joystick or press the fire button at key moments in the animated sequences to govern the hero’s actions. However, the game’s action was more varied with the player occasionally given the temporary option to either have the character he is controlling transform back into his adult form, or remain as a boy with different styles of challenges. Like Dragon’s Lair, Space Ace is composed of numerous individual scenes, which require the player to move the joystick in the right direction or press the fire button at the right moment to avoid the various hazards that hero Dexter / Ace faces. Space Ace introduced a few gameplay enhancements, most notably selectable skill levels and multiple paths through several of the scenes. At the start of the game the player could select one of three skill levels; “Cadet”, “Captain” or “Space Ace” for easy, medium and hard respectively; only by choosing the toughest skill level could the player see all the sequences in the game (only around half the scenes are played on the easiest setting).

A number of the scenes had “multiple choice” moments when the player could choose how to act, sometimes by choosing which way to turn in a passageway, or by choosing whether or not to react to the on-screen “ENERGIZE” message and transform back into Ace. Most scenes also have separate, horizontally flipped versions. Dexter usually progresses through scenes by avoiding obstacles and enemies, but Ace goes on the offensive, attacking enemies rather than running away; although Dexter does occasionally have to use his pistol on enemies when it is necessary to advance. An example can be seen in the first scene of the game, when Dexter is escaping from Borf’s robot drones. If the player presses the fire button at the right moment, Dexter transforms temporarily into Ace and can fight them, whereas if the player chooses to stay as Dexter the robots’ drill attacks must be dodged instead.

A number of the scenes had “multiple choice” moments when the player could choose how to act, sometimes by choosing which way to turn in a passageway, or by choosing whether or not to react to the on-screen “ENERGIZE” message and transform back into Ace. Most scenes also have separate, horizontally flipped versions. Dexter usually progresses through scenes by avoiding obstacles and enemies, but Ace goes on the offensive, attacking enemies rather than running away; although Dexter does occasionally have to use his pistol on enemies when it is necessary to advance. An example can be seen in the first scene of the game, when Dexter is escaping from Borf’s robot drones. If the player presses the fire button at the right moment, Dexter transforms temporarily into Ace and can fight them, whereas if the player chooses to stay as Dexter the robots’ drill attacks must be dodged instead.

Space Ace was made available to distributors in two different formats; a dedicated cabinet, and a conversion kit that could be used to turn an existing arcade cabinet of Dragon’s Lair into a Space Ace game. Early version #1 production units of the dedicated Space Ace game were actually issued in Dragon’s Lair style cabinets. The latter version #2 dedicated Space Ace units came in a different, inverted style cabinet. The conversion kit included the Space Ace laserdisc, new EPROMs containing the game program, an additional circuit board to add the skill level buttons, and replacement artwork for the cabinet. The game originally used the Pioneer LD-V1000 or PR-7820 laserdisc players, but an adaptor kit now exists to allow Sony LDP series players to be used as replacements if the original laser disc player is no longer functional.

Space Ace was made available to distributors in two different formats; a dedicated cabinet, and a conversion kit that could be used to turn an existing arcade cabinet of Dragon’s Lair into a Space Ace game. Early version #1 production units of the dedicated Space Ace game were actually issued in Dragon’s Lair style cabinets. The latter version #2 dedicated Space Ace units came in a different, inverted style cabinet. The conversion kit included the Space Ace laserdisc, new EPROMs containing the game program, an additional circuit board to add the skill level buttons, and replacement artwork for the cabinet. The game originally used the Pioneer LD-V1000 or PR-7820 laserdisc players, but an adaptor kit now exists to allow Sony LDP series players to be used as replacements if the original laser disc player is no longer functional.

Don Bluth animated three Laser Disc arcade games – Dragon’s Lair, Space Ace and Dragon’s Lair II: Time Warp. Even though Dragon’s Lair had been a tremendous arcade gaming success story at first release and would eventually be the forerunner of CD-ROM gaming on home computers, by the middle of 1984 however, after Space Ace, popularity of both these games declined rapidly. Other competitors during the peak arcade gaming years ventured into cartoon animated story games on Laser Disc, but their success would not reach the high peaks of Dragon’s Lair.

Don Bluth animated three Laser Disc arcade games – Dragon’s Lair, Space Ace and Dragon’s Lair II: Time Warp. Even though Dragon’s Lair had been a tremendous arcade gaming success story at first release and would eventually be the forerunner of CD-ROM gaming on home computers, by the middle of 1984 however, after Space Ace, popularity of both these games declined rapidly. Other competitors during the peak arcade gaming years ventured into cartoon animated story games on Laser Disc, but their success would not reach the high peaks of Dragon’s Lair.

However, the Dragon’s Lair legacy continues to live on many years after its arcade gaming demise. In 1986, Publisher, Software Projects, brought Dragon’s Lair to the home computer. The Laser Disc animated tech just could not be replicated to any high standard on 8-Bit computer systems like the Amstrad CPC, ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64.

While the graphics is the main feature of the arcade game, the cartoon graphics were just not possible on 8-Bit home computers of the time. Graphically they were poor adaptations of the original arcade game, there was no Don Bluth doing the artwork or a team of animators, so it was just never going to be graphically outstanding or have the animation of the arcade game. The 8-bit versions had very poor graphics and only about 8 or 9 separate levels to play in comparison to the arcade game. There are very contrasting reviews of the game on 8-Bit platforms.

ZZAP!64, issue 17, seemed to be forgiving of the difficulties of converting a laser disc game to the Commodore 64, giving it an overall score of 69%. They stated the graphics varied between average and very good, but one look and you can see they were being a tad optimistic. Lemon64 forum members are much more scathing in their comments about the C64 conversion, stating that “is was frustrating as hell and very high on difficulty”. In issue 62 of C+VG, they were less forgiving in their assessment of the spectrum conversion, giving it 6 out of 10 for graphics and 3 out of 10 for playability. Amstrad Action, issue 20, gave the CPC version an overall of 67%, stating that “i find it frustrating to the point of insanity”. The home computer game has so many drawbacks such as always dying an early death and always having to restart from the beginning no matter how far you have progressed as well as the dreaded multi load from tape, meant players got sick of the game fairly quickly.

In 1989, video game publisher, Readysoft, released Dragon’s Lair onto the Commodore Amiga. To play the game required 1MB of memory and it consisted of 130 compressed megabytes stored onto six double sided discs, costing a whopping 44.95 pounds sterling. This was seen by many at the time as off putting to gamers and reviewers but the result of its graphics and sounds were simply amazing. The digitized graphics and sounds of the Commodore Amiga version of Dragon’s Lair are by far the best of any home computer version, ACE magazine (April 1989) describing it as “aural and visual excellence”. Although it was not the animated cartoon like the original arcade game, it was the best looking comparison to the arcade game, showing off the amazing capabilities of the Commodore Amiga.

In 1989, video game publisher, Readysoft, released Dragon’s Lair onto the Commodore Amiga. To play the game required 1MB of memory and it consisted of 130 compressed megabytes stored onto six double sided discs, costing a whopping 44.95 pounds sterling. This was seen by many at the time as off putting to gamers and reviewers but the result of its graphics and sounds were simply amazing. The digitized graphics and sounds of the Commodore Amiga version of Dragon’s Lair are by far the best of any home computer version, ACE magazine (April 1989) describing it as “aural and visual excellence”. Although it was not the animated cartoon like the original arcade game, it was the best looking comparison to the arcade game, showing off the amazing capabilities of the Commodore Amiga.

Critics either loved or absolutely hated the game – ST AMIGA Format magazine (March 1989) gave it an overall score of 92% stating “the animation is spell binding. It’s the sort of thing that programmers would gaze at in awe. The characters are animated so smoothly and with accurately moving limbs that you won’t know that you’re not watching a conventional cartoon”. It has “an extraordinary resemblance to the original arcade game. Sound is fairly extensive as well with atmospheric background effects and a range of squeals and screams”. While Commodore User Amiga magazine (March 1989) gave it an overall score of 32%, praising its graphics with a 97% rating and giving its sounds an 80% rating, but it was scathing of its gameplay slating its playability and fun factor giving it just 19%. Reviewer, Mark Heley stated “Dragon’s Lair is an an amazing achievement but who wants to buy an amazing achievement. I’d rather have a game if it’s all the same to you.”

Critics either loved or absolutely hated the game – ST AMIGA Format magazine (March 1989) gave it an overall score of 92% stating “the animation is spell binding. It’s the sort of thing that programmers would gaze at in awe. The characters are animated so smoothly and with accurately moving limbs that you won’t know that you’re not watching a conventional cartoon”. It has “an extraordinary resemblance to the original arcade game. Sound is fairly extensive as well with atmospheric background effects and a range of squeals and screams”. While Commodore User Amiga magazine (March 1989) gave it an overall score of 32%, praising its graphics with a 97% rating and giving its sounds an 80% rating, but it was scathing of its gameplay slating its playability and fun factor giving it just 19%. Reviewer, Mark Heley stated “Dragon’s Lair is an an amazing achievement but who wants to buy an amazing achievement. I’d rather have a game if it’s all the same to you.”

In 1987, Software Projects released an unofficial sequel on Amstrad CPC, Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum home computers, called Dragon’s lair II: Escape from Singe’s Castle. In 1990, Readysoft once again released the game for the Amiga. The release of Dragon’s Lair on home computers had not been a full conversion of the whole arcade game, understandably due to memory constraints, so the unofficial sequel that is Escape From Singe’s Castle includes many of those parts left out. The plot this time though is that Dirk the Daring has returned to the Dragon’s Lair to claim a pot of gold (you save Daphne again in the 16 bit Amiga version).

In 1987, Software Projects released an unofficial sequel on Amstrad CPC, Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum home computers, called Dragon’s lair II: Escape from Singe’s Castle. In 1990, Readysoft once again released the game for the Amiga. The release of Dragon’s Lair on home computers had not been a full conversion of the whole arcade game, understandably due to memory constraints, so the unofficial sequel that is Escape From Singe’s Castle includes many of those parts left out. The plot this time though is that Dirk the Daring has returned to the Dragon’s Lair to claim a pot of gold (you save Daphne again in the 16 bit Amiga version).

Once again, Singe has laid traps throughout his lair, forcing you to guide Dirk across a number of differently themed screens throughout eight levels to steal the gold and finally escape the clutches of the dragon. Once again the controls are awkward and the game high on difficulty. The graphics appear no different but there is more sound and it is rather annoying to the point of you having to turn the sound off, as it is unbearable. The Amiga version of the sequel is once again graphically impressive with lovely sounds but the Amiga gaming community is divided over its ratings – user MCMXC described it on Lemon Amiga “Compared to the first conversion, it is a HUGE improvement: faster load, many options (Including the indication of the moves), multitasking if enough memory available, saving positions and, if got a Hard Disk and the original first game, the possibility of install both of them making one single big game! A very good work! ”. However, user Mailman wrote of the sequel on the Amiga, “Series of the games which are barely playable but full of absolutely amazing graphics (especially when you bear in mind that the conversion was done in years of ECS chipset domination). Nevertheless, seeing does not mean having good fun. Games are not only difficult but also stupid, boring and irritating. Very poor. This is a bit enhanced version of Dragon’s Lair”.

Once again, Singe has laid traps throughout his lair, forcing you to guide Dirk across a number of differently themed screens throughout eight levels to steal the gold and finally escape the clutches of the dragon. Once again the controls are awkward and the game high on difficulty. The graphics appear no different but there is more sound and it is rather annoying to the point of you having to turn the sound off, as it is unbearable. The Amiga version of the sequel is once again graphically impressive with lovely sounds but the Amiga gaming community is divided over its ratings – user MCMXC described it on Lemon Amiga “Compared to the first conversion, it is a HUGE improvement: faster load, many options (Including the indication of the moves), multitasking if enough memory available, saving positions and, if got a Hard Disk and the original first game, the possibility of install both of them making one single big game! A very good work! ”. However, user Mailman wrote of the sequel on the Amiga, “Series of the games which are barely playable but full of absolutely amazing graphics (especially when you bear in mind that the conversion was done in years of ECS chipset domination). Nevertheless, seeing does not mean having good fun. Games are not only difficult but also stupid, boring and irritating. Very poor. This is a bit enhanced version of Dragon’s Lair”.

The third official Don Bluth arcade game, Dragon’s Lair II: Time Warp, was released in the arcades in 1991. It was the first true sequel and released eight years after the original Dragon’s Lair arcade game. Graphically brilliant with superb animation sequences it was once again hampered by a poor control mechanism that plagued the other Don Bluth laserdisc games – Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace.

The third official Don Bluth arcade game, Dragon’s Lair II: Time Warp, was released in the arcades in 1991. It was the first true sequel and released eight years after the original Dragon’s Lair arcade game. Graphically brilliant with superb animation sequences it was once again hampered by a poor control mechanism that plagued the other Don Bluth laserdisc games – Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace.

Another sequel Dragon’s Lair III: The Curse of Mordread was made for Amiga and DOS in 1993, mixing original footage with scenes from Time Warp that were not included in the original PC release due to memory constraints. The game also included a newly produced “Blackbeard the Pirate” stage that was originally intended to be in the arcade game but was never completed.

So you want to play Laser Disc games like Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace ? Well there’s an emulator for that, it’s called DAPHNE (how appropriately named and cool). The DAPHNE laserdisc emulator is free allowing you to play arcade laser disc quality games on your PC. Dragons’s Lair and Space Ace are there, but did you know there were a stack of laserdisc arcade games released throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s? Well Daphne emulator allows you to play almost all of them!

Arcade laserdisc games you can play using Daphne include Astron Belt, Badlands, Bega’s Battle, Cliff Hanger, Cobra Command (running on Astron Belt hardware), Dragon’s Lair (US), Dragon’s Lair II, Esh’s Aurunmilla, Galaxy Ranger, Goal to Go (running on Cliff Hanger hardware), Interstellar, M.A.C.H. 3, Road Blaster, Space Ace (US), Star Blazer, Super Don Quix-ote, Thayer’s Quest and Us vs Them. DAPHNE is developed by Matt Ownby, the latest version being 1.0.12. It runs on Windows, Linux and MacOS. It is a closed-source, multi-arcade LaserDisc emulator. It is also available as a libretro core. You can also use MAME to emulate arcade laser disc games the main differences between MAME and DAPHNE are that DAPHNE is the primary emulator for LaserDisc arcade games and supports many more games than MAME. You can use the DaphneLoader to update DAPHNE and auto download games. MAME supports six LaserDisc games and two that DAPHNE doesn’t support – Cube Quest and Firefox.

Be the first to comment