In the previous two issues of Paleotronic I have written about RPG games, their origins, the games credited with being the first of their kinds on home computers in the RPG video gaming category. Midi Maze on the Atari ST is another one of these ‘very first’ of their kind type of video games that I have the pleasure of researching, learning more about and sharing with the retro gaming community. Before we delve into the game MIDI Maze, let’s take a very brief look at this MIDI business.

So what’s a MIDI ? As I had came to know of it from all the articles I was reading and all the adverts I would see in magazines for such equipment back in the day, I knew it simply as music or more specific as a computer being able to play and create music with equipment such as a keyboard / synthesizer. That was my general knowledge on the subject. It looked and sounded great every time I came across an article about it in a magazine, but I still didn’t fully understand it. I mean I would be at my local video game store and there was no one selling anything else but games and computers to play them on. I never recall seeing any shops promoting they had a MIDI for sale.

Wikipedia explains MIDI as “a technical standard that describes a communications protocol, digital interface, and electrical connectors that connect a wide variety of electronic musical instruments, computers, and related audio devices”. I take one read of that and I am like a 16 year old skipping math class so I can go have some fun playing arcade games with my friends.

What it basically means is that MIDI is a means of getting different electrical / computer equipment together and allowing them to communicate with each other. With the proper software, connections and music related hardware i.e keyboards / synthesizers, what MIDI did and still does is turn your computer into a music making machine. MIDI data can be transferred via a MIDI cable to be recorded to a sequencer for editing and or played back. Before MIDI came along, circa 1983, computers and electronic musical equipment from various manufacturers would struggle to communicate effectively with each other. After 1983 that all changed. With a MIDI compatible computer any other MIDI based electronic equipment could communicate with each other regardless of who the manufacturer was. MIDI also made a universal data file format allowing file sizes to be compacted and allow ease of modification and transfer between computers.

That’s the musical reference of MIDI. Yeah I know, lot’s to take in, if you are like me, you’re not that much into creating music on your computer and all you want to do is play games. Which begs the question, just how did this have anything to do with one of the very first multiplayer, networked, first person shooter (FPS) games, called MIDI Maze, on the Atari ST? When you look back, it seems rather odd that this could even happen.

Before Midi Maze had been released on the Atari ST in 1987, network gaming was not common or even widely thought of in home computer gaming. We’re talking the biggest names in home computer gaming around this time on 8-Bit / 16-Bit machines were the likes of Dizzy (Codemasters), Head Over Heels (Ocean Software), Airborne Ranger (Microprose Software), Wizball (Ocean Software), Double Dragon (Virgin / Mastertronic) and Barbarian (Palace Software). All these other mentioned games are standard one or two player gaming experiences with a single home computer, MIDI Maze being a networked game is clearly the odd one out.

It is strange but also quite perplexing a networked game had even been released during this era, multiplayer games on home computers let alone networked games had no viable market. Big Software players seemed uninterested in taking a look at networked games, why would they bother, they were making huge profits from traditional based gaming. A glimpse of multiplayer network gaming appeared In 1986 with Flight Simulator II being released (by Sublogic) for the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga. It allowed two or more players to connect via a modem or with a Sublogic serial cable.

It is strange but also quite perplexing a networked game had even been released during this era, multiplayer games on home computers let alone networked games had no viable market. Big Software players seemed uninterested in taking a look at networked games, why would they bother, they were making huge profits from traditional based gaming. A glimpse of multiplayer network gaming appeared In 1986 with Flight Simulator II being released (by Sublogic) for the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga. It allowed two or more players to connect via a modem or with a Sublogic serial cable.

From my own memory and experiences at the time, connecting multiple computers to play games against other people seemed like a fantasy, something like the self talking computer in the 1984 movie Electric Dreams. Modems and bulletin boards were still being explored and developed, more likely in the United States, not so much everywhere else. This wasn’t a time in home computer gaming when thought and efforts were focused on multiple machine game playing. Networked gaming would be something you would find only at universities, other than a big multinational corporation, it was the only place feasible to connect multiple machines together. For the average joe buying one computer was fairly expensive buying more than one computer for the home just wasn’t economical or practical. When you think about home computer gaming back then, people were only just starting to buy a second crt tv for the home so that their children could play on the family computer without causing major headaches for other family members who wanted to watch their favourite tv shows the likes Benny Hill, The Bill and Eastenders.

Being a networked game, Midi Maze came out of ‘left field’, firstly because it was not the normal gaming experience and secondly because it was released by a relatively unknown software company – Xanth Software F/X and released through Hybrid Arts. I use the term ‘left field’ because MIDI Maze on the Atari ST just wasn’t normal gaming, more like a radical experiment and Xanth Software F/X had no prior qualifications in this area, they were better known for their earlier release called the Shiny Bubbles graphic demo, it just didn’t compute or make any logic. No one else had even ventured to use a computers MIDI function ports in this way. Everything I had read about, everything I had come to know about MIDI meant music, so how could MIDI mean multiplayer gaming?

The crazy thing is, a ring of networked computers was made simply by using the Midi-in and Midi-out connectors of the Atari ST. It was that easy and yet it hadn’t been done before. Computer 1 Midi-out is connected to Computer 2 Midi-in, Computer 2 Midi-out is connected to Computer 3 Midi-in and so on, the last computer is connected back to Computer 1. This allowed a maximum of 16 Atari ST computers to be connected at the one time to play the same game and so the first of its kind example of a networked multiplayer FPS home computer game was born.

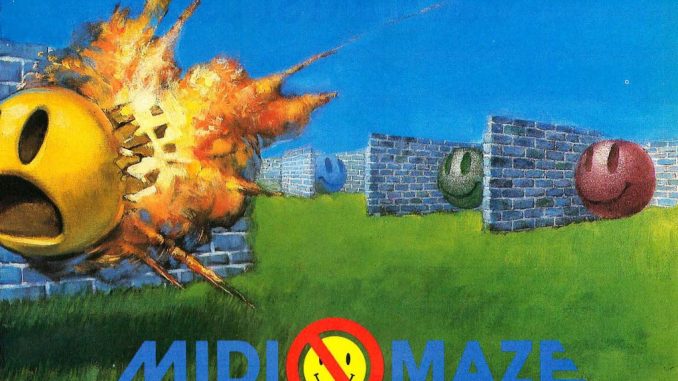

If the network play had been out of ‘left field’ then so had the game itself. When you think of FPS you think of death, destruction, mayhem, blood, bullets flying off in all directions, well it didn’t start that way with MIDI Maze. Instead the player is a Pac-Man like orb in a right angled maze, able to move in any direction and shoot deadly bubbles at other coloured Pac’s. Yes I wrote right and you read correctly – deadly bubbles. Oh my, I have to laugh. This was the origins of competitive deathmatch gaming – shooting deadly bubbles to take out your enemy. Even more unconventional is that the Pac’s are smiling, can you ever imagine playing a FPS like this, I couldn’t but this is how it all began.

To play a game of MIDI Maze, one “master” Atari ST sets the game rules such as revive time, regen time and reload time. It can divide players into teams and select a maze. Many mazes come with the game and additional mazes can be created and played using an editor. The game is played either with joystick or a mouse. If you didn’t have more than one computer connected via Midi ports to play against, you could also play in a one player mode, which pitted you against up to 15 computer controlled bots using three levels of AI, ‘very dumb’, ‘plain dumb’ and ‘not so dumb’, i.e easy, moderate and hard.

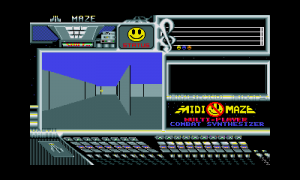

Graphically the game is not what you may think a FPS would look like. There is so much grey used for floors and walls, the only hints of other colours come in the form of the smiley pac’s, the yellow bubbles you fire at them and the blue roof which must represent the sky? The walls are paper thin and without any texture or ambient lighting. The game area occupies only roughly a quarter of the screen and consists of a first person view of a 3D type maze with a crosshair in the middle. What the game does show is that movement around the maze for this particular era of gaming is exceptionally smooth with quite fast frame rates. Maze exploration and movement for avoiding your enemies quickly is probably the best characteristic that came out of the games development. You can shoot at enemies from short or long distances but your aim had to be good as the movement of your enemy was constant, meaning your shots would often miss its intended target. Enemy smileys have a shadow giving perspective to help you out in this regard but it didn’t always materialize in the positive. There is no limits on bullet bubbles, so fire away all you like. The in game sound effects are standard shots being fired, there is no tunes or soundtracks. The whole point of the game is to be the last pac like sphere standing, so its appeal and lastability would be for bragging rights against your other friends hooked up to the network but other than that there was no real sense of achievement.

Graphically the game is not what you may think a FPS would look like. There is so much grey used for floors and walls, the only hints of other colours come in the form of the smiley pac’s, the yellow bubbles you fire at them and the blue roof which must represent the sky? The walls are paper thin and without any texture or ambient lighting. The game area occupies only roughly a quarter of the screen and consists of a first person view of a 3D type maze with a crosshair in the middle. What the game does show is that movement around the maze for this particular era of gaming is exceptionally smooth with quite fast frame rates. Maze exploration and movement for avoiding your enemies quickly is probably the best characteristic that came out of the games development. You can shoot at enemies from short or long distances but your aim had to be good as the movement of your enemy was constant, meaning your shots would often miss its intended target. Enemy smileys have a shadow giving perspective to help you out in this regard but it didn’t always materialize in the positive. There is no limits on bullet bubbles, so fire away all you like. The in game sound effects are standard shots being fired, there is no tunes or soundtracks. The whole point of the game is to be the last pac like sphere standing, so its appeal and lastability would be for bragging rights against your other friends hooked up to the network but other than that there was no real sense of achievement.

While sounding and looking inferior by today’s standards, MIDI Maze took existing home computer gaming into uncharted waters. The original MIDI Maze team consisted of James Yee as the business manager, Michael Park as the graphic and networking programmer and George Miller writing the AI / drone logic, it was these people that made the very first networked, 3D FPS, home computer game possible, it was the pinnacle of network gaming in 1987, now becoming a video game cult classic on the Atari ST today.

Later in 1990, MIDI Maze II by Markus Fritze, for Sigma-Soft, was released as shareware. Watching the video of MIDI Maze II on Youtube gives a much clearer understanding of how 3D FPS became to be known. While the same game setting is used, in MIDI Maze II the FPS experience is much more enhanced than the original MIDI Maze. Included is a compass, an enemy alert indicator, on screen info such as kills, hits, score and money. The use of sound in the form of nightmarish screams to demonstrate a hit being made, is a realization you are in a competitive deathmatch scenario.

Another variation of the game came with WinMaze, based on MIDI-Maze II supporting up to 32 Windows based players networked via LAN with more improvements. It claimed to be “The best MIDI-Maze II clone ever!”. WinMaze was authored by Nils Schneider (with thanks to Jens “Yoki” Unger, who provided socket classes and created the first server version), while Heiko “phoenix” Achilles provided the game’s graphics.

In 1991, a Game Boy version was developed by the original developers, Xanth Software F/X, and published by Bulletproof Software (now Blue Planet Software), under the title Faceball 2000. James Yee, owner of Xanth, had a vision to port the 520ST application to the Game Boy. George Miller was hired to re-write the AI-based drone logic, giving each drone a unique personality trait. It is notable for being the only Game Boy game to support 16 simultaneous players. It did so by connecting multiple copies of the Four Player Adapter to one another so that each additional adapter added another two players up to the maximum – seven such adapters were needed for a full 16 player experience.

A SNES version, programmed by Robert Champagne, was released the following year, supporting two players in split screen mode. The SNES version features completely different graphics and levels from the earlier Game Boy version. A variety of in game music for this version was composed by George “The Fat Man” Sanger. A Game Gear version, programmed by Darren Stone, was released to the Japanese market. It is a colourized version of the monochrome Game Boy edition, supporting two players via two handhelds connected by a cable. A version for the PC-Engine CD-ROM, simply titled Faceball, was also available in Japan.

Be the first to comment