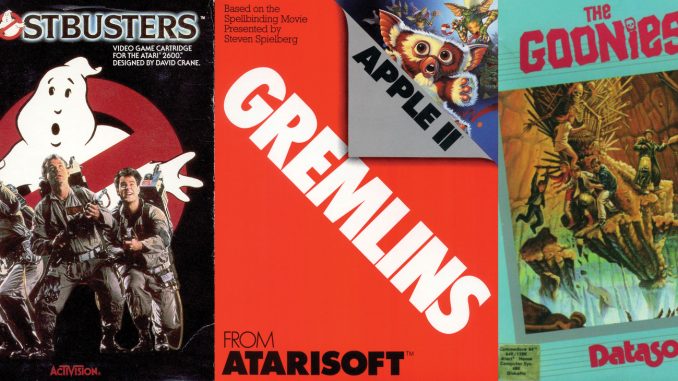

The 1980s are famous for its horror-action-comedy movies, three of the most well-recognised being Gremlins, Goonies and Ghostbusters.

The 1980s are famous for its horror-action-comedy movies, three of the most well-recognised being Gremlins, Goonies and Ghostbusters.

Of course, given their popularity, they all had computer games made for them as well! Let’s take a look at them… while we still have eyeballs to see them with!

A father gives his son Billy a unique pet, a Mogwai, that comes with the warning: “Do not feed after midnight.” Or get wet. Or expose to bright light. Of course, these things happen and hilarity ensues when the pet in question, Gizmo, begins to spawn little green lizard creatures that terrorise the town.

This is the plot of Gremlins (1984) , a comedic horror movie that would eventually gross over US$150 million. Obviously videogame makers wanted to cash in., and at that time Atari had the biggest pockets. First they released a Gremlins game for the Atari 2600, but it was a silly ripoff of other games.

A second version of Gremlins was produced for home computer systems, including the Apple II, Commodore 64 and IBM PC. In it, you control Billy, who has to capture all the Mogwai and return them to their cage, while destroying all the Gremlins with a sword.

A second version of Gremlins was produced for home computer systems, including the Apple II, Commodore 64 and IBM PC. In it, you control Billy, who has to capture all the Mogwai and return them to their cage, while destroying all the Gremlins with a sword.

A text adventure game was also made for the Acorn Electron, BBC Micro, ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64. Based on scenes from the film, some platforms had full colour illustrations.

The better action version of Gremlins would also be released for the Atari 5200, but due to the sale and restructure of Atari, not until 1988, and it would be that console’s last game. In the case of the 5200, the Gremlins ultimately won.

The following year saw the release of The Goonies, a comedy adventure created by Steven Spielberg and Chris Columbus (the same pair behind Gremlins). In it, two brothers discover a treasure map purporting to lead to the fortune of fictional pirate “One-Eyed Willy”. Arrrrrrgh!

The brothers hope to recover the treasure and use it to stop property developers from evicting them from their housing complex in order to build a golf course. They team up with several of their friends, and collectively calling themselves “the Goonies” they set off to find the treasure, but discover the entrance is hidden beneath a restaurant inhabited by a crime family made up of a matriarch and her three sons.

One of the sons, severely disfigured Lotney – cruelly nicknamed ‘Sloth’ by his brothers – decides to help the Goonies. The movie was fairly successful (although not as successful as Gremlins), with a worldwide gross of $US60 million.

This time it was software publisher Datasoft that would win the rights to release a Goonies videogame. It’s a puzzle / platform game where the player controls two of the Goonies (one at a time) in order to solve each puzzle and move on to the next level.

There are eight levels in total, with the last one(the pirate ship) requiring specific Goonies to accomplish specific tasks. The retail version of the game came with a ‘hint sheet’ containing a rhyme for each level, such as “Rocks that crush, pots that pour, bats that fly, you can’t ignore.”

There are eight levels in total, with the last one(the pirate ship) requiring specific Goonies to accomplish specific tasks. The retail version of the game came with a ‘hint sheet’ containing a rhyme for each level, such as “Rocks that crush, pots that pour, bats that fly, you can’t ignore.”

The game received mostly positive reviews, with computer gaming magazines giving it an average of 7/10.

While Gremlins and The Goonies were certainly successful films, neither would even come close to touching the crown held by Ghostbusters. Released in 1984, Ghostbusters was a runaway hit, with an eventual worldwide gross of $US295 million!

In the movie, three former parapsychology (the study of hypnosis, telepathy, etc.) professors set up a ghost removal service in New York City, after encountering a ghost in the public library. Luckily for them, a further rash of supernatural occurances kickstarts their otherwise floundering business, and the ‘Ghostbusters’ soon set off to look for the source of them.

Activision successfully negotiated the license to produce a game of the movie, which was initially designed by David Crane, wh o had previously produced a number of titles for both Atari and Activision including Outlaw (Atari 2600) and, most famously, Pitfall!

o had previously produced a number of titles for both Atari and Activision including Outlaw (Atari 2600) and, most famously, Pitfall!

Crane wrote the game, initially released for the Atari 800 and Commodore 64, but later for the Apple II, Sinclair Spectrum, Amstrad CPC and MSX, in about six weeks. He managed this by basing the game on an incomplete game called Car Wars that featured armed cars roving around a city, leading to the in-game concept of buying items, such as a ‘ghost vacuum’ with which to outfit the Ecto-1, the car driven by the Ghostbusters in the movie. The final week of development was spent orchestrating the Ghostbusters song for the title screen.

In the game, the player moves from location to location on a map, controlling the Ghostbusters as they capture ghosts. As you do so, you earn money you can use to buy better equipment, such as a PKE Meter which lets you see where ghosts will appear next. Eventually you face off against the Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man.

Ghostbusters would later be ported to a number of consoles including the Atari 2600, Sega Master System and Nintendo Entertainment System, the latter more difficult than the other versions and ending with some humorously bad ‘Engrish’.

The movie was so popular there was a 1989 sequel, which was of course followed by a sequel computer game, Ghosbusters II. Once again published by Activision, the (non-DOS) game features three distinct levels based on scenes from the film. In the first, Ray is lowered into a subway tunnel to collect slime while using three different weapons to deter various spirits. The second level has the player shoot fireballs from the Statue of Liberty at ghosts while it walks along Broadway. Finally, the third level has the player safely insert the Ghostbusters into the art museum, where they battle Vigo.

The game was released for the Amiga, Amstrad CPC, Atari ST, Commodore 64 and ZX Spectrum. It was praised for its graphics and sound but many reviewers found the gameplay lacking and the constant disk-swapping infuriating.

A tale of three companies

In 1979 a number of Atari game designers, including future Ghostbusters programmer David Crane, decided they had had enough and left to start their own videogame company. They found an attorney, Jim Levy, who helped them secure US$1 million in funding and who coined the name Activision as a portmanteau of ‘active’ and ‘television’.

Levy would also serve as CEO and keep Atari off of their backs while the designers concentrated on making new games. With their knowledge of the Atari 2600, they were able to create games that used special tricks that made them distinctive from Atari-produced games.

In 1982, Activision released Crane’s Pitfall!, which was a hit and sold more than 4 million copies. By 1983 Activision had US$60 million in revenue and 60 employees. Through Levy’s leadership, Activision managed to survive the 1983 videogame crash, and despite a number of other challenges it has lived on to the present day.

Datasoft was founded in 1980 by Pat Ketchum. Based in Chatsworth, California, Datasoft mostly produced titles licensed from arcade games, movies and TV shows, including arcade hits Pole Position, Mr Do!, Pooyan and Zaxxon, and screen-inspired titles such as Goonies, Bruce Lee, Zorro and Dallas Quest. Datasoft is also known for a number of other titles such as the Alternate Reality series, Canyon Climber, O’Riley’s Mine and Tomahawk.

After Atari was sold to Warner Communications, the new management treated its game developers less like rockstars and more like the house band, giving them no credit for the games they produced nor the sorts of royalties others in the industry were receiving at the time.

And so, many of the developers left to start their own companies, including Activision and Imagic. Warners was not impressed.

In response, Atari attempted to enforce ownership of the intellectual property behind the Atari 2600, claiming that the knowledge of how to interface cartridges with the console was a ‘trade secret’ and that Activision’s founders had ‘stolen’ it. Eventually, Activision agreed to pay royalties to Atari, which legitimised third-party game development, and opened the door to other companies to develop not just for the 2600 but for later consoles as well.

Atari would itself get into the third-party development game by releasing versions of its games for non-Atari hardware under the Atarisoft brand name (purportedly to avoid causing confusion with consumers, but more likely so they weren’t labeled hypocrites).

Be the first to comment