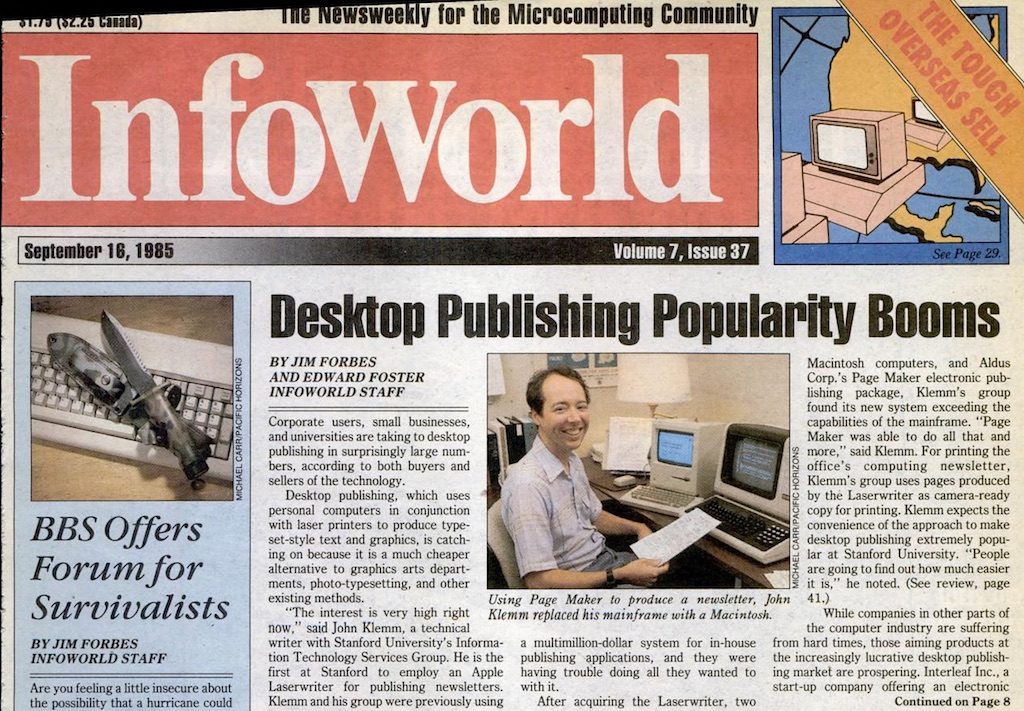

HOW TO MAKE MONEY USING COMPUTERS…

sounds like the title of a bargain book, but in the late 1980s it was a dream-come-true for many a budding desktop publisher.

Or it was for some of them, anyway…

The print industry prior to then had been an extremely mechanical one, all the way back to the invention of the printing press.

To produce a publication, you arranged text blocks and image plates on a rack, coated them with ink and stamped them on paper. This was a time-consuming process that involved a number of different people, and a lot of back-and-forth to get things just right.

It was also a very difficult industry to get into, with high start-up costs and all sorts of gatekeepers with little appetite for outside-of-the-box ideas (or outside-of-the-box people, for that matter).

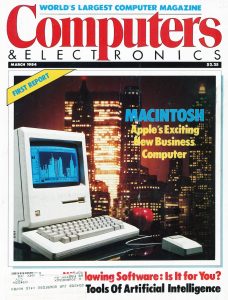

But the Macintosh changed all of that. For around the cost of an average car, you could buy a Mac, a laser printer and some software, and with a little talent you (yes, just you!) could produce ‘print-ready’ documents that could be copied or turned into plates for printing presses. Anyone could become their own print shop.

But the Macintosh changed all of that. For around the cost of an average car, you could buy a Mac, a laser printer and some software, and with a little talent you (yes, just you!) could produce ‘print-ready’ documents that could be copied or turned into plates for printing presses. Anyone could become their own print shop.

This was a complete paradigm shift. Gone were the gatekeepers, the power of Big Print over the industry significantly weakened, the doors thrown open to all and sundry who wished to throw off the shackles of employment, mortgage their houses and start their new lives as owners of their own businesses. A flourishing new cottage industry quickly emerged and thousands of people found happiness in their new careers.

Sounds great, doesn’t it? If only it had been that easy.

Of course, Apple was in the business of selling computers, and so the ‘desktop publishing (as graphic design was known at the time) gold rush’ that emerged in the years after the release of the Macintosh suited them nicely. They weren’t shy about exploiting people’s desires for financial and professional freedom, either, running advertising campaigns that touted the Mac’s ease-of-use. If you bought into the hype, the Macintosh could give anyone the ability to do almost anything.

Of course, Apple was in the business of selling computers, and so the ‘desktop publishing (as graphic design was known at the time) gold rush’ that emerged in the years after the release of the Macintosh suited them nicely. They weren’t shy about exploiting people’s desires for financial and professional freedom, either, running advertising campaigns that touted the Mac’s ease-of-use. If you bought into the hype, the Macintosh could give anyone the ability to do almost anything.

But while it was true that the Macintosh was easier to use than other personal computers that came before it, it wasn’t magical, and it couldn’t bestow instant talent on its user, as much as those who had just spent several thousand dollars on one may have dreamt it could.

Training prospective desktop publishers became as lucrative as desktop publishing itself (if not more so) as new Macintosh owners rushed to pull their rapidly smouldering new careers out of the fire.

Of course, ads like the one to the left (for Ready Set Go, one of several desktop publishing software packages) didn’t help. But since when has advertising ever been truly honest?

Of course, ads like the one to the left (for Ready Set Go, one of several desktop publishing software packages) didn’t help. But since when has advertising ever been truly honest?

Happily for some it wasn’t completely hopeless, and armed with both technology and talent, they marched into the future…

However, when they got there it wasn’t pretty. Sure, they could undercut traditional typesetters and do small-batch publishing much cheaper than the big printing houses, but unless you had the luxury of being the only desktop publisher in town (unlikely) then you would have been forced to deal with competitors – competitors as anxious as you were to establish themselves, and as willing as you were to do whatever it took to survive.

As in any industry some competed on price, and drove each other out of business. Some attempted to compete on quality, but while there is value in more sophisticated design, for most people a brochure was a brochure and they inevitably selected based on price.

It also didn’t help that every computer-savvy kid whose parents bought them a Mac (or an Atari ST, or an Amiga) quickly realised they could pirate a desktop publishing program and put themselves out there. It was better than mowing lawns!

And so, those outfits that survived tended to be the ones who got into the magazine game, providing design and layup for niche publications that couldn’t afford to have dedicated staff. Some were tasked with creating advertisements for clients of these publications, and then branched out into designing corporate logos and advertisements for clients more directly. Low-end, unsophisticated commercial ‘desktop publishing’ largely fell away (left to the kid with the Atari) and morphed into graphic design.

Meanwhile, the Macintosh evolved, shifting from monochrome to colour, and software evolved with it, allowing for in-the-box photo editing and layout of colour publications. Cut-and-paste publishing was completely abandoned, with entire publications being produced digitally, photographs and artwork scanned in, stored on hard disks and sent to the printer on CD-ROM.

Meanwhile, the Macintosh evolved, shifting from monochrome to colour, and software evolved with it, allowing for in-the-box photo editing and layout of colour publications. Cut-and-paste publishing was completely abandoned, with entire publications being produced digitally, photographs and artwork scanned in, stored on hard disks and sent to the printer on CD-ROM.

Laser printers became faster, cheaper and colour themselves, allowing for quick proofing and client approvals. Computer speed increases provided additional freedom to designers, who could iterate more quickly and produce better designs. Publications became more sophisticated.

As the graphical capabilities of computers increased, combined with the power of the Internet the World Wide Web was born. While initially extremely primitive in terms of design, advances such as CSS and Javascript / HTML 5 have led to an on-line world rich in sophisticated websites and content, a world that couldn’t have existed without computers such as the Macintosh and those pioneers who risked their livelihoods by rushing headlong into the largely uncharted territory that was desktop publishing.

However, the web has not been kind to the print industry, with newspapers and magazines largely replaced by cheap or free on-line versions, those themselves preyed upon by content ‘recyclers’ who post slightly re-worded versions of articles on their own sites in the quest for advertising revenue. It’s still uncertain how the print media industry is going to survive in the long term, and it ultimately may not survive at all, with the production of well-researched content moving exclusively to the domain of video.

Although bad for print media, the Internet has arguably improved access to information in general, a net benefit.

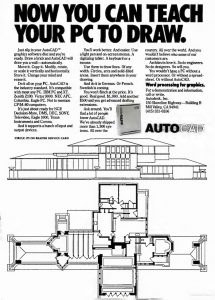

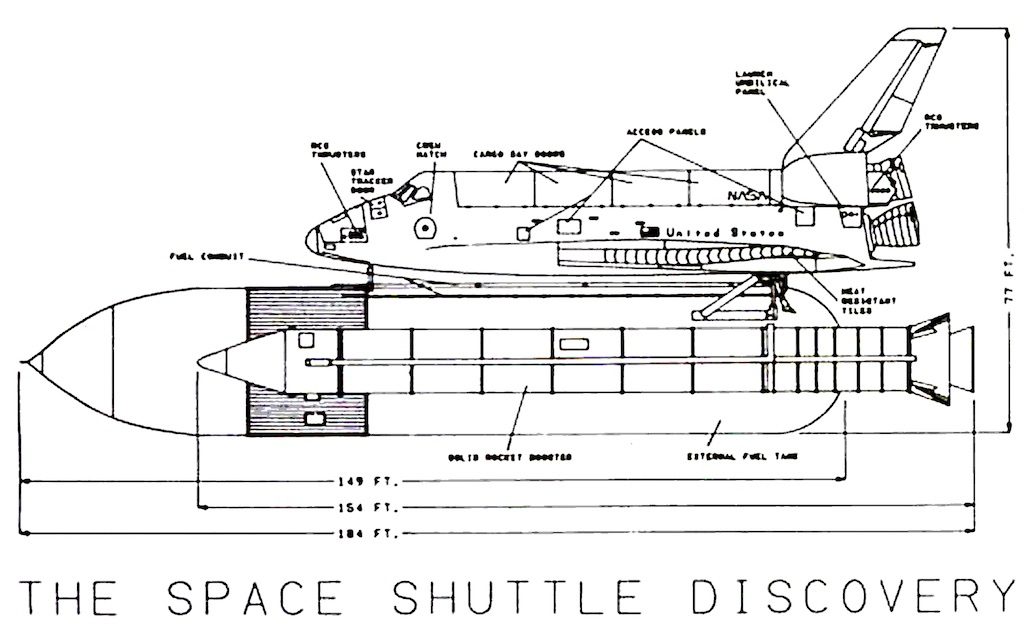

Computers can be used to design more than just corporate logos and magazines! CAD (Computer Aided Drafting or Design) leverages the capabilities of computers to replace the tedious process of pencil-on-paper drafting.

No longer do iterations necessitate new drawings (or extensive erasure). Making a change is as simple as deleting or altering a line. You can recycle drawings into new ones, by reusing parts of a drawing, or combine parts from different drawings, for example floorplans or other repetitive designs. You can create templates to speed up new drawings. And when you’re done you can print them using Postscript or another printing language to ensure the highest quality output, or e-mail them to whoever needs them, no pulp required.

CAD made a brave new world for drafting. But how did we get here?

In 1977, Michael Riddle started development on a program called Interact CAD. Interact ran on a minicomputer, a computer smaller than a mainframe computer but still designed to have multiple terminals connected to it, sharing its CPU and other resources. Interact did all of the calculations needed to create new drawings or change them, and with guaranteed accuracy.

But minicomputers were quite expensive and out of the reach of most smaller drafting firms, which meant they were still stuck using a drafting desk and a t-square – as they had been for hundreds of years. In order to make Interact CAD more accessible, it needed to be able to run on microcomputers – personal computers.

Autodesk was founded in 1982 by Riddle, John Walker and 14 other co-founders. They intended to develop a number of ‘automation’ applications that streamlined aspects of various industries, hoping that one of them would take off. That turned out to be AutoCAD, a conversion (or ‘port’) of Interact CAD to the CP/M (Control Program for Microcomputers) computing platform.

CP/M was an operating system created in 1974 for Intel 8080 / 8085 processors running inside S-100 (or Altair) bus-based computers. The private use of CP/M computers by hobbyists was the impetus for the introduction of consumer-oriented ‘personal’ computers. But more importantly, CP/M and S-100 combined to make a standard method of designing and working with a computer, and this made software more portable.

Up until that time you typically had to compile software on a new computer, making changes to suit its particular methods of operation, and this typically had to be done by the software vendor, who was protective of their source code! But with CP/M, you could just send a customer a disk or tape.

This meant that AutoCAD could be sold and installed much more cheaply than Interact CAD, and work on much cheaper hardware. This, combined with being the only player willing to take a risk in developing microcomputer software for the drafting market, led to AutoCAD’s widespread adoption. By 1986, four years after its introduction, AutoCAD had overtaken all other CAD programs, running on mainframes, minicomputers or otherwise, to become the most used CAD application in the world.

This meant that AutoCAD could be sold and installed much more cheaply than Interact CAD, and work on much cheaper hardware. This, combined with being the only player willing to take a risk in developing microcomputer software for the drafting market, led to AutoCAD’s widespread adoption. By 1986, four years after its introduction, AutoCAD had overtaken all other CAD programs, running on mainframes, minicomputers or otherwise, to become the most used CAD application in the world.

It’s a very good example of how personal computers could (and would) dramatically change an industry. It’s also a very good example of how a niche market could become dominated by a single application – while engineering and architecture firms were happy to train their employees up on the first software package to show a benefit (and AutoCAD’s benefits were enormous), they’re far less likely to re-train up those employees on another package regardless of additional benefits (unless they are very substantial), which means the first package they buy is likely to be the one they stay with until they’re forced to move to something else.

AutoCAD was that software. And Autodesk was here to stay.

Indeed, since Autodesk launched AutoCAD at the COMDEX trade show in Las Vegas in 1982, there have been 31 versions of the software, some running on MS-DOS, then Windows and then Macintosh. AutoCAD is used in construction, animation, architecure and more.

But while AutoCAD would rule the roost for decades to come, competitors still attempted to take a slice of its pie.

However, no one ever came close to AutoCAD’s market share. This was in part because computing publications loved AutoCAD: not only was Autodesk successful in getting a new industry to computerise, they also advertised a lot which didn’t hurt.

Also, crucially perhaps, Autodesk also developed a good software package and supported it well, and there was no reason for anyone to go anywhere else.

Be the first to comment