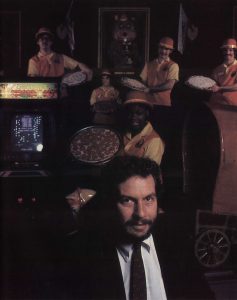

Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell was facing a serious conundrum.

His ‘video computer system’, a cartridge-based home video-game console designed to play versions of popular Atari arcade games, was certain to be a big hit, but in developing it he had burned through all of his company’s cash. Retailers who had made big money on Atari’s home Pong machines were interested in selling it but they wanted terms – that is, they wanted to get stock now but pay for it later. So Nolan couldn’t use pre-orders (no such thing in 1976!) to fund manufacturing and as a result the VCS was essentially dead in the water. His only solution was to sell equity to get the money to move into production.

But he was going to need to sell so much equity that he was going to lose control of Atari. Can you imagine what it was like to be Nolan Bushnell? He was going to have to sell his company in order to make it successful! Not a great decision to be forced to make.

So, in the end, he sold Atari to Warner Communications, which ponied up the cash to manufacture the VCS and the rest is history. But what happened to Nolan Bushnell? What did he do?

He made pizza.

He studied electrical engineering at Utah State University and the University of Utah. While attending college, he worked for an amusement park, an engineering outfit, started his own advertising company and sold encyclopedias door-to-door – each of these experiences would influence Bushnell’s later direction.

After his time with Atari and Chuck E. Cheese, Bushnell founded Catalyst Technologies, one of the earliest business incubators. Catalyst-affiliated companies included Androbot, which developed home robots, Etak, which was the first company to provide digitized maps, and CinemaVision, which attempted to develop high-definition television.

Currently Bushnell is CEO of BrainRush, a company that develops gamified education software.

Doesn’t seem like much of an evil master plan does it? Sell your world-conquering video game company to make pizza? But Bushnell did have a plan, it just wasn’t evil. See, videogames had been considered an adult thing ever since their inception, really. Arcades were seedy places, and kids were generally not welcome (and their parents didn’t want them there anyway!) But Bushnell had realised there were two paths to bring his games to children: a home videogame console (the Atari VCS), and a ‘family-friendly’ video arcade.

Well, to reach the end of the first path he had to sell his company. But in doing so, he was in a position to travel the second. And on that road is where we get into pizza, and a rat. Not Bushnell (contrary to his detractors’ insinuations he was a pretty upstanding guy), but a pizza-schlepping rat of his invention named Chuck E. Cheese.

Bushnell may have seen the writing on the wall regarding his future at Atari, since in 1977 he started developing the concept of the pizza restaurant as an ‘employee’ of the company he co-founded, opening a ‘test’ location in San Jose, California in 1977. Bushnell’s design of the restaurant was inspired by his time working at Lagoon Amusement Park in Utah while he attended college, a mix of food, carnival games and attractions.

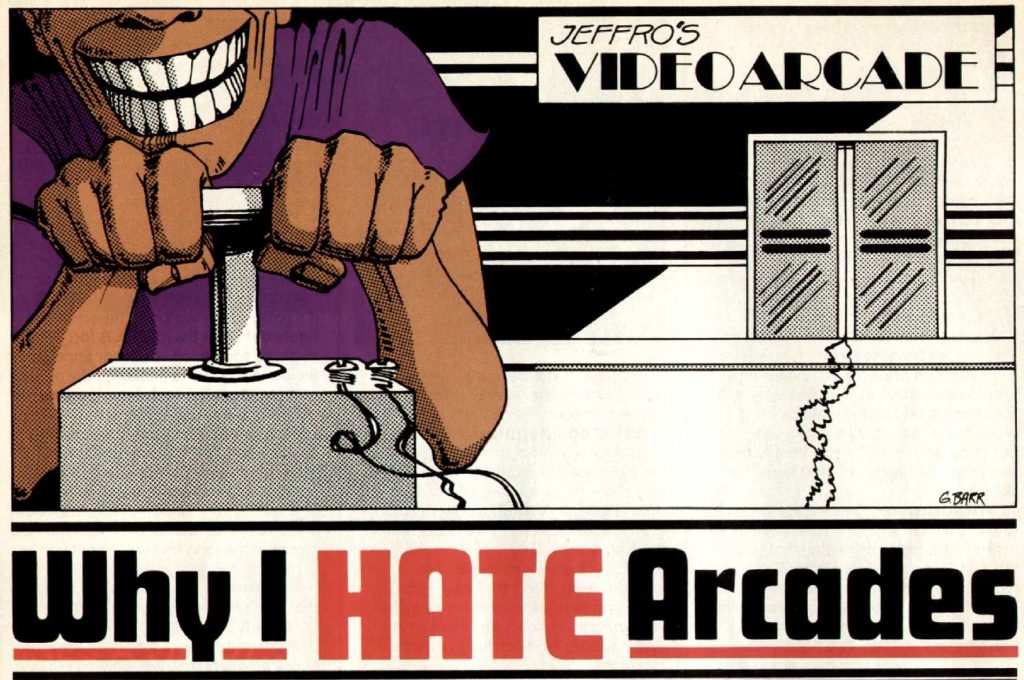

Named the ‘Pizza Time Theatre’, he duplicated the amusement park on a smaller scale, providing pizza (selected because it was cheap and simple to make and easy to ‘scale up’ in the event of a sudden large influx of patrons, for example a birthday party), arcade games and a Disney-inspired animatronic ‘show’ as the attraction. The show was initially meant to be led by a coyote – maybe an homage to (or an attempt to cross-license) Warners’ Wile E. Coyote – but Bushnell ordered the wrong costume, which when it arrived was revealed to be a rat.

For many 1980s kids in the US and Canada, Chuck E. Cheese’s was the local video arcade, other places containing videogames considered off-limits to children. This made them popular locations for birthday parties! As a result, many a Saturday afternoon would be spent there, by thousand of children on hundreds of Saturdays from then until today.

Nolan Bushnell originally wanted to call him Rick Rat, but Chuck E. Cheese was chosen instead.

Over the last 40 years, this rat has sold a lot of pizza!

Always the economiser, rather than order another costume Bushnell decided to change the prospective name of the restaurant from Coyote Pizza to Rick Rat’s Pizza, but unsurprisingly his marketing people didn’t like the new name, suggesting Chuck E. Cheese instead as if the rat were a 19th-century showman – plus it sounded friendlier to parents.

But, while the restaurant looked like it had potential, the inevitable arguments between Bushnell and Warner Communications regarding Atari’s direction in other matters ensued and in 1978 they came to a head, with Bushnell being shown the door. On the way out he bought the rights to the pizza restaurant off of Warners (who probably didn’t see the value in it anyway). However, fortunately for Bushnell, Pizza Time Theatre’s customers had a different opinion, and he began expanding the company to other locations in California, and entering into franchise agreements to expand across the United States.

But just like the arcades whose reputation Bushnell was trying to reform, business could be a shady… well, business. During his efforts to expand he met Robert Brock of Topeka Inn Management in 1979. Bushnell gave Brock the exclusive franchising rights for sixteen states across the southern and midwestern US.

However, Brock had no loyalty to Bushnell, which he demonstrated quite clearly only months later. After meeting a potential competitor, Brock was frightened by what he deemed to be that competitor’s ‘superior’ animatronic technology, and he jumped ship, teaming with the competitor to create another chain of similar restaurants called ShowBiz Pizza Place (not similar at all!) Bushnell sued, and ShowBiz settled out of court, agreeing to pay a portion of its profits to Pizza Time Theatre over the following decade.

Both chains were commercially successful, and in 1981 Pizza Time Theatre went public. But the effects of the 1983 video game crash were keenly felt by both Pizza Time and Showbiz, whose patrons had grown tired of videogames. Bushnell, who had stepped away to start Catalyst Technologies, a venture capital group, returned in an effort to save the company but despite the sale of two Pizza Time subsidiaries – Sente Technologies, which developed an arcade system that used cartridges, and Kadabrascope, an early computer-animation company sold to George Lucas and which eventually became Pixar – Pizza Time eventually went broke, and with Bushnell unable to raise any money (as he had already borrowed significant amounts using his Pizza Time stock as collateral to start Catalyst) Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatre went bankrupt. It looked as if the rat was dead.

However, ShowBiz Pizza, while wounded by the crash, was less encumbered by debts and was able to raise the cash to purchase Pizza Time’s assets. They continued to operate Chuck E. Cheese’s as a separate chain until 1989, when the two chains were unified under the Chuck E. Cheese brand.

As for Nolan Bushnell, was his initial mission, to make arcades more family friendly, successful? Arguably, yes it was. In the late 1970s the primary locations for arcade video games were in pubs and pool halls, and while stand-alone video arcades had begun to proliferate, they typically still catered to an adult-specific audience, with ashtrays affixed to the sides of arcade cabinets and even trays to hold drinks. Some of them even featured racy videogames, film-based ‘peep shows’ and even live nudity shows ‘in the back’.

Given their nature, they also attracted less-savoury elements of the community such as drug dealers, sex workers and bookkeepers. As you might imagine, these operations drew the ire of the authorities and more conservative-minded residents of the jurisdictions in which they were located, and the media seized on that concern, amplifying it and making arcades (and by extension arcade games) the root of all the world’s evils.

Even arcades that didn’t have XXX-rated attractions and welcomed younger patrons found themselves pilloried by their communities, blamed for truancy, poor grades and drug use by children – as if such troubles had never existed prior. City and town councils began to ban arcades, or severely limit their sizes and/or locations. The hysteria became so pronounced that the US Department of Justice dictated arcade game manufacturers place a message inside the attract mode of their games advising players not to use drugs!

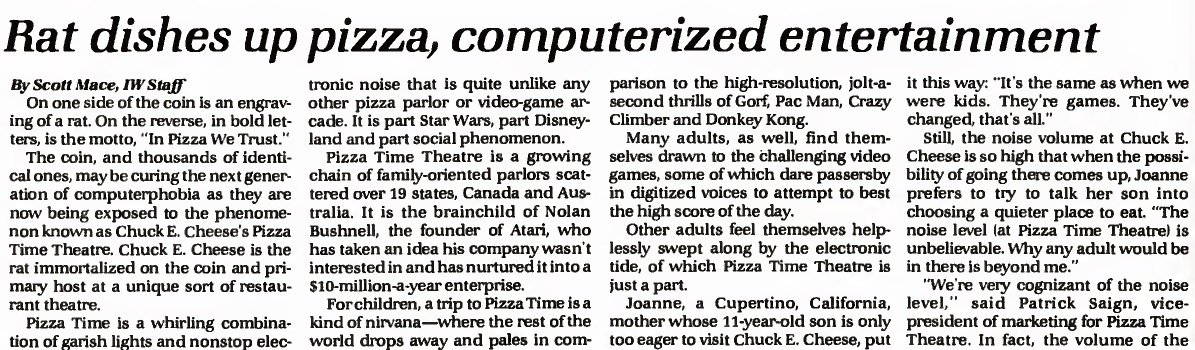

This had a severe chilling effect on thoughts by prospective arcade owners of opening new establishments, and this in turn was noticed by arcade game manufacturers such as Atari, which wanted to do what it could to reform the image of arcades and get lawmakers to back off. It started a newsletter, Atari Coin Connection, not only to inform arcade owners of new games, but to showcase family-friendly establishments in an attempt to encourage other arcade owners to emulate their ‘success’ and work with the local community to allay fears and concerns.

Atari also pointed to Chuck E. Cheese’s to demonstrate that family-friendly establishments could be profitable. In response, the focus of new arcades gradually shifted away from an adult ‘anything goes’-type environment to more child and teen-friendly venues that avoided dark corners, cooperated with police and school officials, and were more selective about who they admitted. Many ‘amusement centres’ were opened in shopping centres, which had security cameras and uniformed patrols.

Atari also pointed to Chuck E. Cheese’s to demonstrate that family-friendly establishments could be profitable. In response, the focus of new arcades gradually shifted away from an adult ‘anything goes’-type environment to more child and teen-friendly venues that avoided dark corners, cooperated with police and school officials, and were more selective about who they admitted. Many ‘amusement centres’ were opened in shopping centres, which had security cameras and uniformed patrols.

Eventually, outside of downtown locations in major cities, most of the smoky, seedy arcades of the 1970s went extinct.

Unfortunately, their reputation did not die with them. Despite their attempts at running more community-friendly operations, arcade owners still faced frequent criticism whenever any youth-related incident occurred for which blame could be even tenuously assigned to them, and ‘arcade hysteria’ reared its ugly head on and off well into the late 1980s and early 1990s when the focus shifted instead to videogame violence.

Regardless of puritan efforts, video arcades became popular (and generally safe) hangouts for teenagers, and will forever be remembered by those generations that experienced them, thanks in large part to Nolan Bushnell.

Be the first to comment