What could be better than connecting to another computer remotely? How about remotely connecting remotely?

While these days we take the ‘always connected’ nature of our mobile phones for granted, back in the early 1980s the idea of being able to access information on-the-go was mindblowing. Most people learned about current events passively, either through the newspaper, the radio or the 6 o’clock TV news. If you wanted more practical information you had to look it up in an encyclopedia, or call someone to look it up in an encyclopedia. And if you needed to compute, you had to be near a computer!

While these days we take the ‘always connected’ nature of our mobile phones for granted, back in the early 1980s the idea of being able to access information on-the-go was mindblowing. Most people learned about current events passively, either through the newspaper, the radio or the 6 o’clock TV news. If you wanted more practical information you had to look it up in an encyclopedia, or call someone to look it up in an encyclopedia. And if you needed to compute, you had to be near a computer!

With a modem, it was just as easy to become dependent on instant access to information, real-time news updates and social connections then as it is now, and for your 1980s digital pioneer the idea of portability – being able to do whatever you did in your computer room at home anywhere else – was the Holy Grail.

The first step in this crusade was the Tandy Pocket Computer PC-1, a rebranding of the Sharp PC-1211. Released in 1980, it was an advancement over previous ‘programmable calculators’ in that it had a QWERTY keyboard and allowed for the writing and execution of BASIC code. It had a 24-character LCD and could run for up to 300 hours on four coin-style watch batteries! But while it had the ability to load and store programs from tape and print to a tiny portable thermal printer, sadly it didn’t have a modem.

For that, prospective payphone warriors would have to wait until the PC-2. Released in 1982, this second revision of the Pocket Computer featured much better hardware specifications than the PC-1, although it was larger and weighed over double that of its predecessor.

The PC-2 was much more like what would consider a portable computer, with a better processor, more memory (which could be expanded with 4KB and 8KB memory modules), the ability to display bitmapped graphics and a monophonic sound generator and speaker.

The PC-2 was much more like what would consider a portable computer, with a better processor, more memory (which could be expanded with 4KB and 8KB memory modules), the ability to display bitmapped graphics and a monophonic sound generator and speaker.

But most importantly, along with the cassette and printer interfaces of its predecessor, it had an RS232C (serial) interface, which added additional communications-oriented commands to the built-in BASIC language and allowed the PC-2 to be connected to a modem.

By typing in a short little ‘terminal program’ (and acquiring or building a battery-powered acoustic modem) you could call up Compuserve or your local bulletin-board system (BBS) from the comfort of a Superman-style 1980s payphone box (payphone box not always available).

By typing in a short little ‘terminal program’ (and acquiring or building a battery-powered acoustic modem) you could call up Compuserve or your local bulletin-board system (BBS) from the comfort of a Superman-style 1980s payphone box (payphone box not always available).

So, not quite the same as using Facebook on your mobile phone. But in the early 1980s this was crazy high-tech, when you consider your alternatives for contacting someone on-the-go were either to call them (and if they weren’t there leave a message on their answering machine or with whoever did answer and hope they actually passed along the message) or page them (if they had a pager which was pretty rare unless you were a doctor or a dope dealer). E-mail was easier!

But once you factor in the US$199 cost of the PC-2 plus the US$199 cost of the RS232C interface and then the cost of the acoustic modem (around the same), that ~US$600 price tag (over US$1500 in 2018) was a bit out of reach of your average 12 year-old. But a kid can dream, right?

Of course, if a kid did have the wherewithal to get their hands on such a rig they could get into all kinds of trouble – the anonymity granted by using payphones (in an era where security cameras were uncommon) led to all kinds of successful (and not-so-successful) hacking attempts. But if you were a more law-abiding citizen (yeah, I’m talking about you, Pointdexter), there’s plenty of other things you could do with your Pocket Computer that didn’t attract the unwanted attention of federal authorities.

For one, you could learn how to code! Computer professionals in the 1980s tended to treat BASIC with derision, but let’s face it, these days most parents are happy if their children spend 15 minutes playing around with Scratch. I imagine they’d be ecstatic if their child wrote their own terminal program, even if it was in BASIC and they did use it to try to break into NASA! Little Jimmy could also catalogue his comic book collection, or calculate the position of the stars, or cheat on his final mathematics exam (you go Jimmy!)

For one, you could learn how to code! Computer professionals in the 1980s tended to treat BASIC with derision, but let’s face it, these days most parents are happy if their children spend 15 minutes playing around with Scratch. I imagine they’d be ecstatic if their child wrote their own terminal program, even if it was in BASIC and they did use it to try to break into NASA! Little Jimmy could also catalogue his comic book collection, or calculate the position of the stars, or cheat on his final mathematics exam (you go Jimmy!)

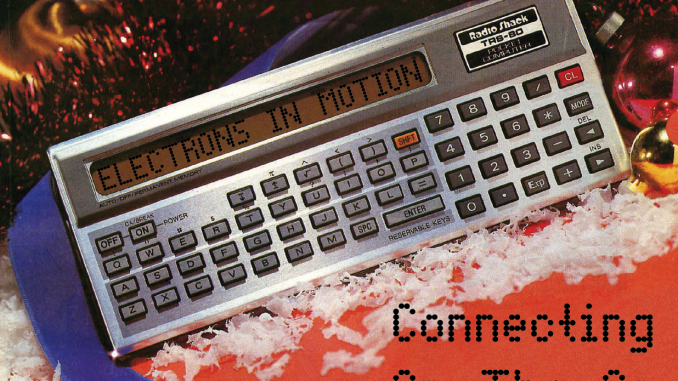

And so, maybe to prevent that last bit, you might want to get Jimmy something a little more conspicuous. The TRS-80 Model 100, introduced in 1983, was roughly the size of a textbook, with a full-sized keyboard and an 8-line 40-character wide display – definitely a step up on the Pocket Computer. And it ran on AA batteries! Only US$1099 (around US$2800 in 2018) – ouch.

And so, maybe to prevent that last bit, you might want to get Jimmy something a little more conspicuous. The TRS-80 Model 100, introduced in 1983, was roughly the size of a textbook, with a full-sized keyboard and an 8-line 40-character wide display – definitely a step up on the Pocket Computer. And it ran on AA batteries! Only US$1099 (around US$2800 in 2018) – ouch.

That’s an expensive Christmas present for Jimmy! But, think of all he could do with it. Aside from word processing, like the Pocket Computer it had a full built-in BASIC, programmed in part by Bill Gates himself (in fact, the last code he ever wrote). He could even use BASIC to control the internal 300 baud modem – not that Jimmy would ever recognise the potential that combination had to get himself in a lot of trouble!

But one thing’s for sure, Jimmy would’ve been the coolest kid in class – at least until another kid beat him up and took it from him (ah, the 80s, such a wonderful time to be a nerdy kid). People still think the Model 100 is cool today, there’s a thriving online community of owners.

The press loved the Model 100, not just as a product, but its portability, full-sized keyboard and built-in modem made it perfect for the journalist on-the-go. Being battery powered meant there was no need to deal with adapting the Model 100 to local electricity standards, and once you filed your report via modem you could erase it and avoid confrontation with government officials when exiting less-savoury countries. But that’s not all: the Model 100 had an address book and a scheduling program – both at that point in time typically scrawled out on paper.

The press loved the Model 100, not just as a product, but its portability, full-sized keyboard and built-in modem made it perfect for the journalist on-the-go. Being battery powered meant there was no need to deal with adapting the Model 100 to local electricity standards, and once you filed your report via modem you could erase it and avoid confrontation with government officials when exiting less-savoury countries. But that’s not all: the Model 100 had an address book and a scheduling program – both at that point in time typically scrawled out on paper.

While the Pocket Computer and the Model 100 were trailblazers, they proved there was a market for lightweight portable computers and over time various companies such as Casio and Epson would release their own products, both in the ‘notebook’ and pocket categories.

While the larger form-factor of the Model 100 would eventually be replaced by laptop computers and portable dedicated word-processors, the Pocket Computer would evolve into the ‘palmtop’ and the PDA.

While the larger form-factor of the Model 100 would eventually be replaced by laptop computers and portable dedicated word-processors, the Pocket Computer would evolve into the ‘palmtop’ and the PDA.

Initially, however, the former would be stripped of its ability to run customised applications, and instead manufacturers released ‘pocket organisers’ which were glorified calculators that came with versions of the Model 100’s address book and calendar programs. Some could even generate touch tones and dial your phone!

But in the early 1990s technology made it practical for a pocket-sized PC, and in 1991 Hewlett-Packard released the HP95LX, an MS-DOS compatible computer with 1MB of RAM. While running DOS on a tiny computer was cool, palmtops didn’t really take off until the advent of Windows CE, first released in 1996.

The Philips Velo 1, for example, released in 1997 was a Windows CE palmtop that featured a touch-sensitive monochrome screen (four shades of grey with the update to Windows CE 2.0) and a built-in low-power modem (unlike competitors, which needed a PCMCIA modem ‘card’). It also allowed users to run custom applications, such as games and Microsoft Office.

However, in the late 1990s palmtops would be overtaken by Palm-style personal digital assistants (PDAs), with pen recognition taking over from the keyboard.

Be the first to comment