![]() Upon viewing Moonsweeper for the first time the word ‘wow’ just doesn’t seem to do it justice, yet it’s the first word to form in most people’s brains.

Upon viewing Moonsweeper for the first time the word ‘wow’ just doesn’t seem to do it justice, yet it’s the first word to form in most people’s brains.

It just seems to trite, so simple, yet your mind is unable to figure out another phrase that justifies what you are seeing before the word has already made its way to your mouth and the exclamation has been uttered.

While most games from the early 80s were simple, 2D affairs, Moonsweeper featured a semi-3D playing field and fast paced action. It broke rules by not having a scoring system, instead having the player build up energy or fuel reserves. In 1982 games most games were designed to played endlessly, with the gamer attempting to improve their high score with each play. However, Moonsweeper was able to be completed, though the game is difficult to get through.

According to the manual, your mission is ‘to reach and rescue miners stranded on hostile moons in Star Quadrant Jupiter!’ You are warned to be cautious as you venture across the hostile moons of Jupiter, rescuing miners who have been left stranded for reasons the manual fails to explain. Whatever the reason, Jupiter’s surrounding lunar bodies have become mini war zones and the lives of those miners are at risk.

As you start the game you find yourself flying through space, with objects coming at you from all directions. It can be a little confusing to know what you need to do if you haven’t read the manual. Luckily in the information age that can be found online and reading it is recommended if you want to know how to progress through the levels. The idea is to destroy or avoid everything except the moons, you want to head for them. Upon reaching one the game area will change you flying across the lunar surface, attempting to find and rescue miners. Once this is done you head back out into space to find the next moon. The game ends when you die or complete all of the moons.

As you start the game you find yourself flying through space, with objects coming at you from all directions. It can be a little confusing to know what you need to do if you haven’t read the manual. Luckily in the information age that can be found online and reading it is recommended if you want to know how to progress through the levels. The idea is to destroy or avoid everything except the moons, you want to head for them. Upon reaching one the game area will change you flying across the lunar surface, attempting to find and rescue miners. Once this is done you head back out into space to find the next moon. The game ends when you die or complete all of the moons.

Released in 1983, Moonsweeper wasn’t the first successful title by developer Imagic. Classic titles such as Atlantis and Demon Attack could already be found on store shelves, though at the time it was unusual to see games released by a third party developer.

It was David Crane, Larry Miller and Bob Whitehead who set up Activision in 1979, the world’s first company for creating games. Frustrated at the lack of recognition developers were given, he decided to set up a new company where coders were credited for the games they made. Prior to this the hardware manufacturers would handle the development and marketing of any games that were to be released on the system. After what they felt to be poor treatment from Atari, the men left the company but continued to do what they did best, make games, as Activision. Another Atari alum, Larry Kaplan, joined the trio shortly after, just as the lawsuit was about to hit. Atari decided to flex its corporate muscle and take the men to court.

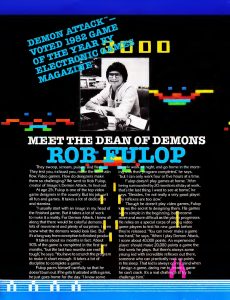

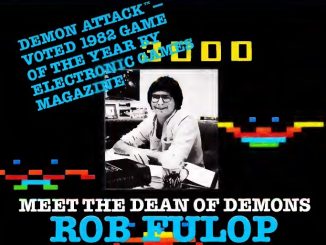

The legal struggles between Atari and Activision would continue until 1982, but in the meantime other Atari employees found themselves facing the same situation as David Crane and co. Rob Fulop was one such employee, and he, like the Activision coders, liked the idea of creating a brand new third party development company. 21 months after the founding of Activision, Rob, along with other disgruntled Atari and Mattel employees, set up the world’s second third party developer, Imagic.

Bill Grubb provided the Mattel connection, having worked on licensing for Mattel as well as Atari. During one of his visits in Mattel, Jim Goldberger, who Bill had previously attempted to bring over to Atari, approached him about starting up an ‘Activision-type company.’ Bill took this proposal seriously and discussed the idea with Jim until 2AM the following morning. From there he created a business plan and sought funding to get Imagic started.

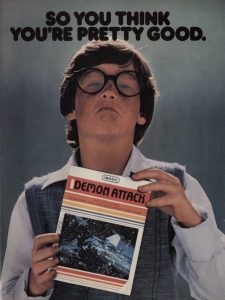

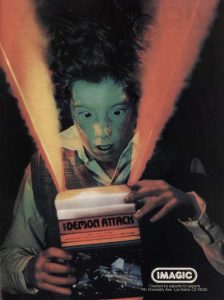

The video game boom was in full swing in the early 80s, and there was plenty of money around for people who wanted to become a part of this new industry. Atari games were selling at an alarming rate, so much so that in Christmas 1981 there was a shortage of cartridges. Most likely due to the success of the industry, Rob claims that setting up Imagic was not a difficult process. The men started work on their first release, Demon Attack, a game based on the highly successful Galaga. The game was a best seller, netting the company a ‘Game of the Year’ award from Billboard. Fulop was finally starting to receive the recognition he was deprived of at Atari.

Demon Attack was not Imagic’s only success story in its first year. Dennis Koble’s Atlantis was another monster hit, though was eclipsed by Fulop’s monster hit. One of the earliest examples of a tower defence game, Atlantis saw you controlling the defensive canons to fend off attacking Gorgon invaders. Dennis Koble was not a fan of licensing existing games and was always looking for new ideas to work on. He felt that Imagic should be licensing its games to other companies rather than just taking on existing properties. However, Bill Grubb, ever the businessman, was not too concerned about how they made money, as long as they continued to do so.

While Atari appeared to be too distracted by Activision to take on a second third party developer, they did take issue with Demon Attack’s resemblance to Phoenix. Imagic was taken to court over the similarities between the games, though the case was settled out of court.

While Atari appeared to be too distracted by Activision to take on a second third party developer, they did take issue with Demon Attack’s resemblance to Phoenix. Imagic was taken to court over the similarities between the games, though the case was settled out of court.

Fulop produced another space faring adventure with Cosmic Ark for the Atari 2600. Perhaps taking inspiration from Star Wars, this futuristic game was set in the distant past. Like Moonsweeper, the game is a rescue mission set on various planets “a long time ago in a galaxy far far away…”. Sales were half that of Demon Attack, though the game was still highly successful. After developing the Atari 2600 port of Missile Command, Demon Attack and Cosmic Ark, he decided that he wanted a change of pace. Space was a fun environment to play around in, but a creative mind needs to expand beyond the familiar to grow.

The result of these changes became Cubicolor, a puzzle game that could not be further removed from Demon Attack if he tried. Rob took inspiration from the Rubik’s Cube when developing the game, which ended up as a colour matching game. The game was too far removed from the heavy titles Imagic was currently churning out and Cubicolor’s prospects were deemed to be poor. While the game was completed it was never released, leaving Rob with around 100 copies of the game sitting on EPROM chips.

While Imagic were becoming a success and its developers were receiving the recognition that eluded them at Atari, the employees remained grounded. Activision were known for treating their coders like super stars, though according to Bill Grubb and Dennis Koble the culture of Imagic was rather subdued in comparison. According to Grubb, while the coders wanted to be recognised for the games they were making they had no desire to become the dictionary definition of famous. Recognition and fame are two different things, and while the line can be fine at times, the Imagic employees had private lives outside of their work.

While Imagic were becoming a success and its developers were receiving the recognition that eluded them at Atari, the employees remained grounded. Activision were known for treating their coders like super stars, though according to Bill Grubb and Dennis Koble the culture of Imagic was rather subdued in comparison. According to Grubb, while the coders wanted to be recognised for the games they were making they had no desire to become the dictionary definition of famous. Recognition and fame are two different things, and while the line can be fine at times, the Imagic employees had private lives outside of their work.

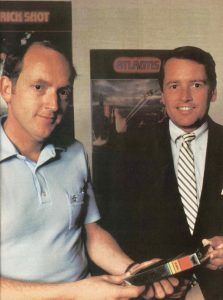

By January 1983, Imagic had grown from its original 9 founding members to over 80 employees. The company had also set up offices in a larger office building in Los Gatos. In the January 1983 issue of ‘Video Games’ magazine, fellow founding member and Imagic president Bill Grubb discussed the differences between themselves and Activision. In his words Imagic were doing things “more aggressively” and were focusing on releases for multiple systems, whereas Activision had narrowed their market to the Atari 2600 and Mattel Intellivision.

This rapid growth drew the attention of the New York Times, who predicted sales in excess of $75 million. They credited Fulop’s Demon Attack as being one of the leading contributors to the success of the business, which was set to become the world’s first public video game company. Their arrival on Wall Street was set to be a huge success. Imagic had talented coders and a well put together management team. Arnie Katz of the trade publication Electronic Games claimed that “they have everything going for them”. The wheels were to be set in motion in the following 12 months.

The problem with success is that it comes with its own set of problems. Maintaining consistency at a high level can be tricky, and it doesn’t take much to bring it all crashing down. In 1982 Imagic struck a deal with Texas Instruments do develop games for the TI series of computers. What could be seen as a coup for Imagic quickly became a pressing concern as the stock prices for Texas Instruments dropped by over 40% in a single week and the company started to report huge losses. Within the company this was seen as a significant setback, though it was one they felt they could recover from. They may have been able to do so, though another significant event was about to happen that would impact not only Imagic, but the entire industry.

Imagic was moments away from going public when the video game crash of 1983 bought down the entire video game industry. While Howard Warsaw’s E.T. is seen as the main catalyst for the crash, history shows that complacency was the biggest problem. People couldn’t get enough of video games, as evidenced by the huge sales of 1981. While the disappointing E.T. can definitely be seen as a contributor, the quality of games in general was on the decline. The Atari 2600 port of Pacman is seen by many as unnecessarily lazy and dull.

Imagic was moments away from going public when the video game crash of 1983 bought down the entire video game industry. While Howard Warsaw’s E.T. is seen as the main catalyst for the crash, history shows that complacency was the biggest problem. People couldn’t get enough of video games, as evidenced by the huge sales of 1981. While the disappointing E.T. can definitely be seen as a contributor, the quality of games in general was on the decline. The Atari 2600 port of Pacman is seen by many as unnecessarily lazy and dull.

While Imagic was fo rced to withdraw its IPO the crash was something it could recover from. The company had made some smart decisions in the past year, including providing support for the home computer market, specifically the Commodore 64, VIC 20 and IBM PCjr, and ignoring some of the more questionable machines that hit the already oversaturated console market. Bill Grubb was always hesitant to support the Atari 5200 and decided to sit on that decision until the console had proven itself. He felt that if Atari were doing as well as they claimed then they would not have to release a new home console.

Despite this Rob Fulop claims that the crash had a significant impact on the management team at Imagic and the place was never the same after it happened. By the time the crash happened the company had in excess of 100 employees, over a quarter of which were laid off. Video game retailers were starting to push for changes to the inventory policies, allowing them to purchase less games and hold the developers liable for some of the losses they may incur.

Imagic made deals with retailers, allowing them to buy back old stock to make room for new stock. While this may sound like a good idea these cartridges need to be put somewhere, so storage costs were added on top of the buy back scheme. Imagic were forced to sell over $10 million of its own private stock to cover the costs. Meanwhile, the less aggressive Activision continued to do well, despite taking a hit along with the rest of the industry. The philosophy of Activision was to focus on the quality of the games rather than expansion. In the end it was a simple case of, they had less to lose.

While the end was fast approaching, the management of Imagic attempted to continue developing games for the home computer market. The 1984 CES saw Imagic debut four new titles for the IBMjr. The new president, Bruce Davis, declared that Imagic would only be focusing its development on home computers. Unfortunately this move came too late and the company was forced to fold shortly after.

Today the back catalogue of the world’s second ever third party company sits with Activision, the world’s first ever third party company. Along with their own back catalogue, Activision will occasionally release various titles from the Imagic back catalogue for modern systems, keeping the spirit of the aggressive group of third party developers alive and well.

Be the first to comment