The first mechanical light-gun games appeared in the arcades and midways of the 1930s. Following the invention of the light-sensing vacuum tube, companies such as Seeburg produced games that had the tube hidden inside targets, which would drop when “hit” by a beam of light emanating from a toy rifle. This included the first light-gun “duck hunt” game.

The first mechanical light-gun games appeared in the arcades and midways of the 1930s. Following the invention of the light-sensing vacuum tube, companies such as Seeburg produced games that had the tube hidden inside targets, which would drop when “hit” by a beam of light emanating from a toy rifle. This included the first light-gun “duck hunt” game.

Several other electro-mechanical games appeared throughout subsequent decades, culminating in Japanese manufacturer Sega’s first arcade hits, including 1966’s Periscope and 1972’s Killer Shark.

Following the 1972 release of the first home video-game system, the Maganvox Odyssey, and its Shooting Gallery game, mechanical light-gun arcade games began to be replaced with video-based ones. However, rather than emanating light, as in the mechanical games, the gun used in video-based games detected it.

There were three methods used. The first method, used by the Odyssey, simply detected if the rifle was pointing at a bright-enough light source when the trigger was pulled. It assumed that the player was pointing the rifle at the screen, and that the only source of light would be a target. Similar arcade games mounted the gun on a stand with fixed movement, to prevent cheating.

There were three methods used. The first method, used by the Odyssey, simply detected if the rifle was pointing at a bright-enough light source when the trigger was pulled. It assumed that the player was pointing the rifle at the screen, and that the only source of light would be a target. Similar arcade games mounted the gun on a stand with fixed movement, to prevent cheating.

Once video targets progressed past being mere spots of light and into full-colour sprites, a second, slightly more sophisticated method was developed. When the trigger on the gun was pulled, the screen would blank, and a silhouette of each potential target on the screen would light up sequentially (or all of them at once, in poorly programmed games).

If the gun sensed light at the right time, the game assumed where it was pointing. This was the method used by Nintendo’s light gun, called the Zapper. Like Sega, Nintendo had also manufactured several electro-mechanical light gun games in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including the first incarnation of Wild Gunman, a “wild west”-style dueling game in 1974. But after arcades were fully conquered by video games, the company focussed on developing joystick-controlled titles.

If the gun sensed light at the right time, the game assumed where it was pointing. This was the method used by Nintendo’s light gun, called the Zapper. Like Sega, Nintendo had also manufactured several electro-mechanical light gun games in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including the first incarnation of Wild Gunman, a “wild west”-style dueling game in 1974. But after arcades were fully conquered by video games, the company focussed on developing joystick-controlled titles.

When Nintendo attempted to get the Nintendo Entertainment System into North American toy stores in the mid-1980s without success, it was determined that the console would be more palatable to retailers if it had “extras” that distinguished it from then-shunned consoles such as the Atari 2600, which had stung them in the 1983 video-game crash.

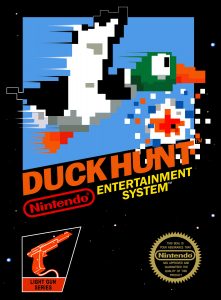

Two extras were eventually chosen to be launched with the console: a toy robot called R.O.B., and a light gun – the Zapper. To be as family-friendly as possible, the Zapper’s companion game was Duck Hunt, an animated duck and clay-shooting game “hosted” by a humorous hunting dog that mercilessly mocked the player whenever they failed to shoot any targets (darn that dog!) Due to the simplistic nature of the light gun, most Zapper games use large, spread-out targets, such as Hogan’s Alley, available for purchase separately at the NES’s launch in 1985.

Due to its being packed-in with the majority of NES consoles sold (usually on the same cartridge as Super Mario Brothers) Duck Hunt can easily be declared the most-played light-gun game of all time, a favourite of tens of millions of children who grew up in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The cartoonish nature of both gun and game also pleased parents, who would’ve been more reluctant about allowing their youngsters to shoot at more realistic targets!

Due to its being packed-in with the majority of NES consoles sold (usually on the same cartridge as Super Mario Brothers) Duck Hunt can easily be declared the most-played light-gun game of all time, a favourite of tens of millions of children who grew up in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The cartoonish nature of both gun and game also pleased parents, who would’ve been more reluctant about allowing their youngsters to shoot at more realistic targets!

However, games involving human targets were much more popular in video arcades. 1984’s Hogan’s Alley was one of those – the player was tasked with shooting (video) cardboard-cutout criminals at a police-style target range while not shooting the innocent bystanders. Nintendo allowed a version of the game to be produced for the NES’s launch in 1985 because the targets weren’t “real”.

Sega was not to be outdone. With the launch of the Sega Master System the following year, in 1986 it also introduced a light gun it called the Light Phaser. A companion cartridge was also released; called Safari Hunt in European and other markets, players shot at fixed, clay and animal targets, but in North America the animal portion was removed out of concern parents would object to the shooting of mammals such as bears, and it was more plainly titled Marksman Shooting & Trap Shooting – a real mouthful!

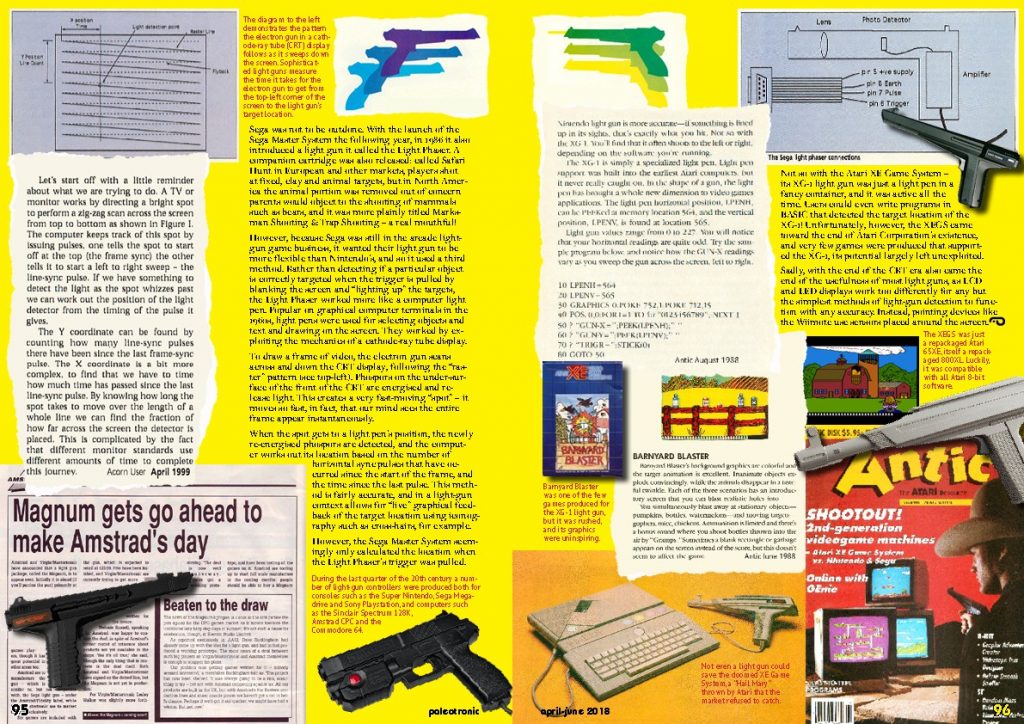

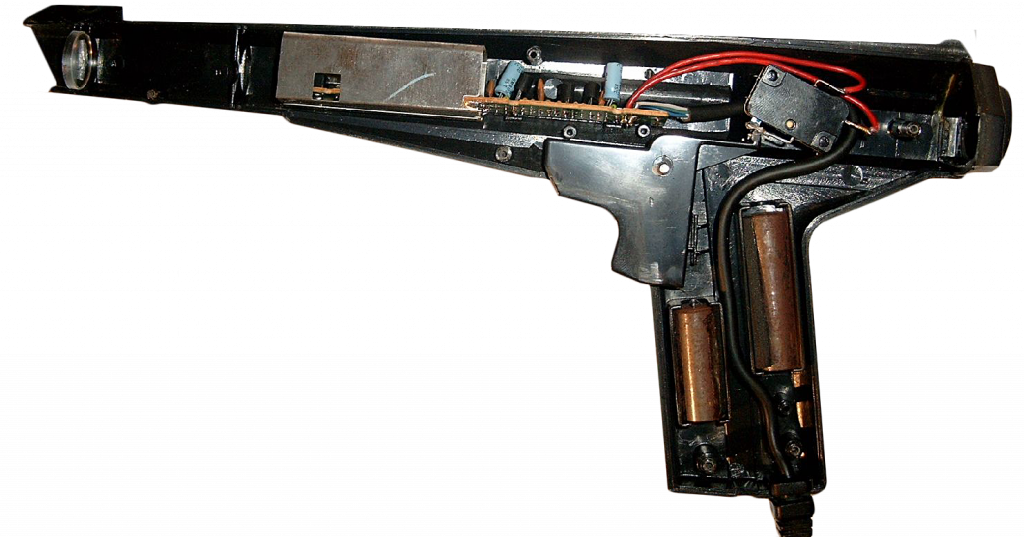

However, because Sega was still in the arcade light-gun game business, it wanted their light gun to be more flexible than Nintendo’s, and so it used a third method. Rather than detecting if a particular object is correctly targeted when the trigger is pulled by blanking the screen and “lighting up” the targets, the Light Phaser worked more like a computer light pen. Popular on graphical computer terminals in the 1960s, light pens were used for selecting objects and text and drawing on the screen. They worked by exploiting the mechanics of a cathode-ray tube display.

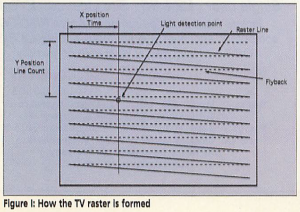

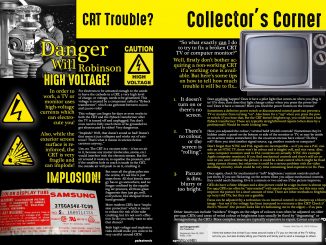

To draw a frame of video, the electron gun scans across and down the CRT display, following the “raster” pattern (see left). Phospors on the under-surface of the front of the CRT are energised and release light. This creates a very fast-moving “spot” – it moves so fast, in fact, that our mind sees the entire frame appear instantaneously.

When the spot gets to a light pen’s position, the newly re-energised phospors are detected, and the computer works out its location based on the number of horizontal sync pulses that have occurred since the start of the frame, and the time since the last pulse. This method is fairly accurate, and in a light-gun context allows for “live” graphical feedback of the target location using iconography such as cross-hairs, for example. However, the Sega Master System seemingly only calculated the location when the Light Phaser’s trigger was pulled.

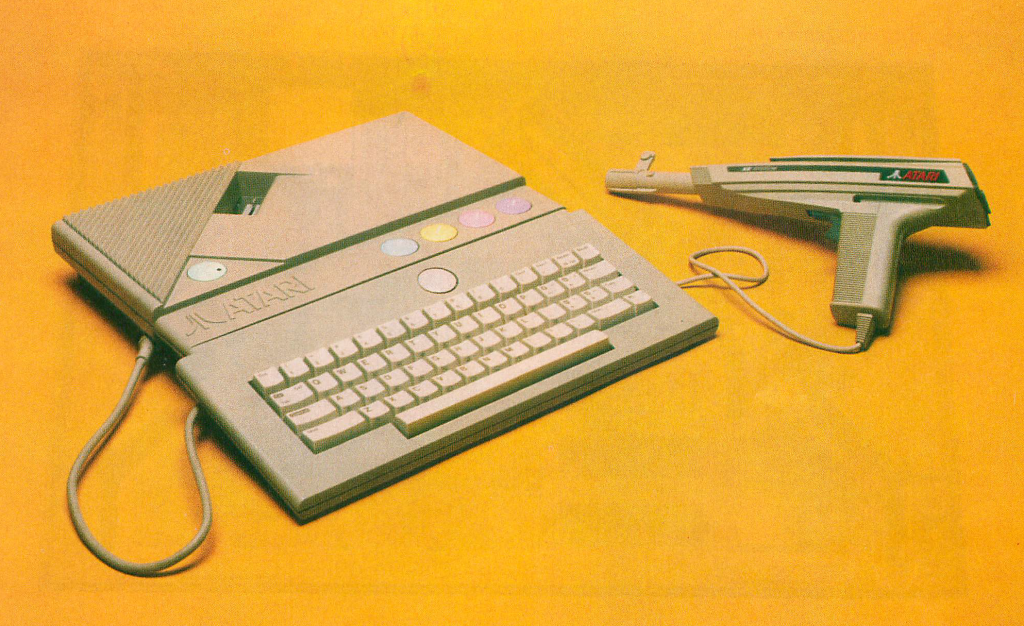

Not so with the Atari XE Game System – its XG-1 light gun was just a light pen in a fancy container, and it was active all the time. Users could even write programs in BASIC that detected the target location of the XG-1! Unfortunately, however, the XEGS came toward the end of Atari Corporation’s existence, and very few games were produced that supported the XG-1, its potential largely left unexploited.

Sadly, with the end of the CRT era also came the end of the usefulness of most light guns, as LCD and LED displays work too differently for any but the simplest methods of light-gun detection to function with any accuracy. Instead, pointing devices like the Wiimote use sensors placed around the screen.

Be the first to comment