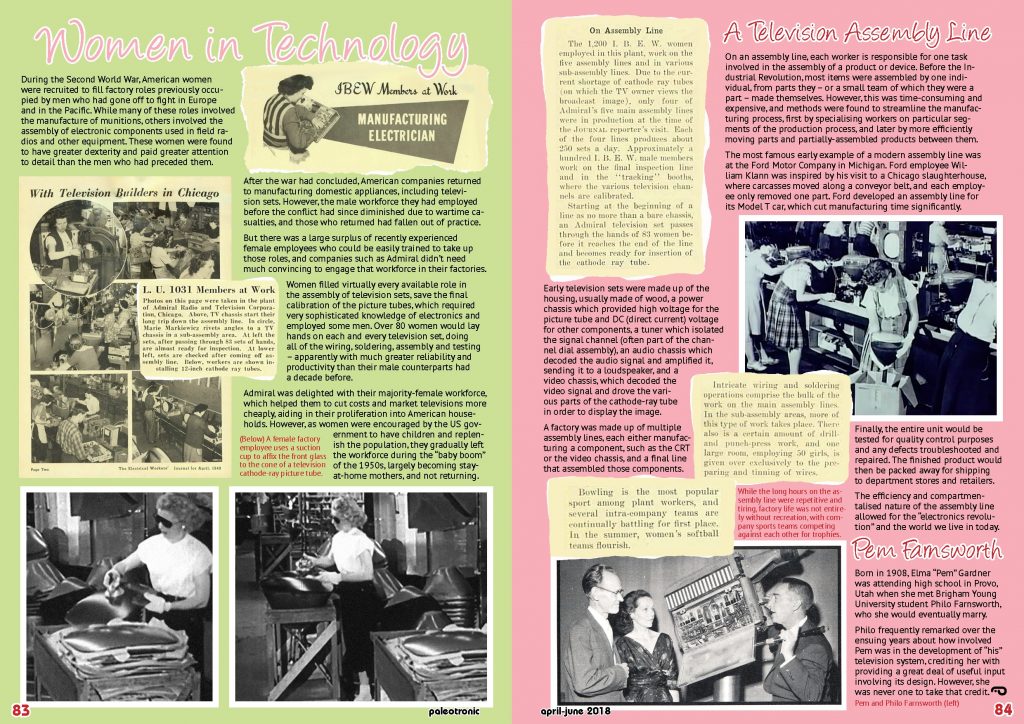

During the Second World War, American women were recruited to fill factory roles previously occupied by men who had gone off to fight in Europe and in the Pacific. While many of these roles involved the manufacture of munitions, others involved the assembly of electronic components used in field radios and other equipment. These women were found to have greater dexterity and paid greater attention to detail than the men who had preceded them.

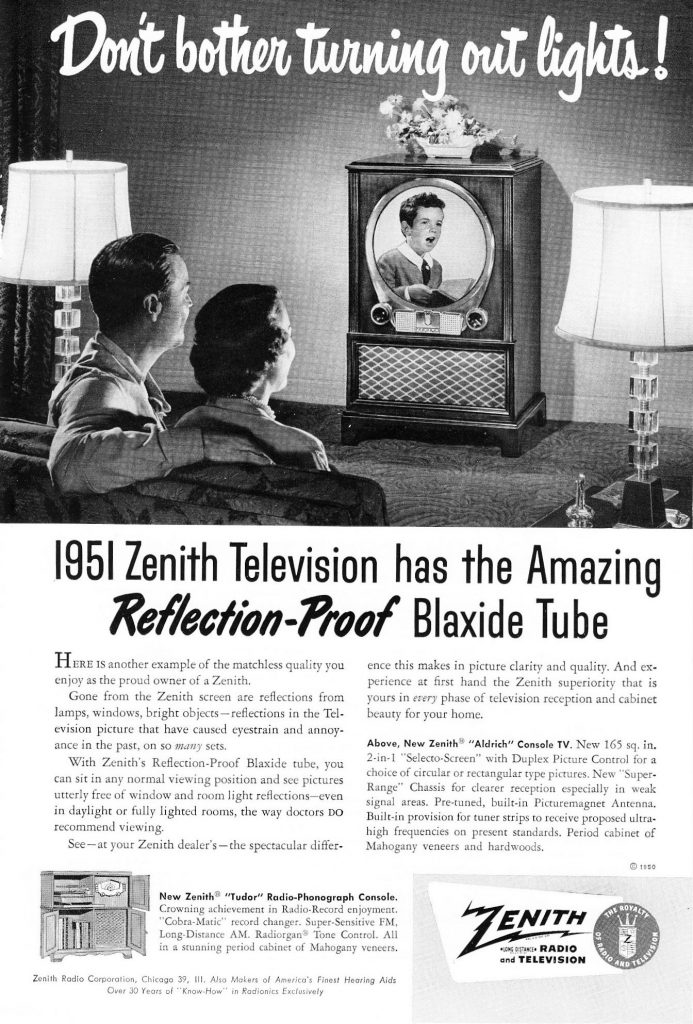

After the war had concluded, American companies returned to manufacturing domestic appliances, including television sets. However, the male workforce they had employed before the conflict had since diminished due to wartime casualties, and those who returned had fallen out of practice.

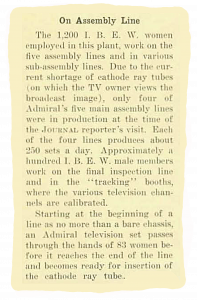

But there was a large surplus of recently experienced female employees who could be easily trained to take up those roles, and companies such as Admiral didn’t need much convincing to engage that workforce in their factories.

But there was a large surplus of recently experienced female employees who could be easily trained to take up those roles, and companies such as Admiral didn’t need much convincing to engage that workforce in their factories.

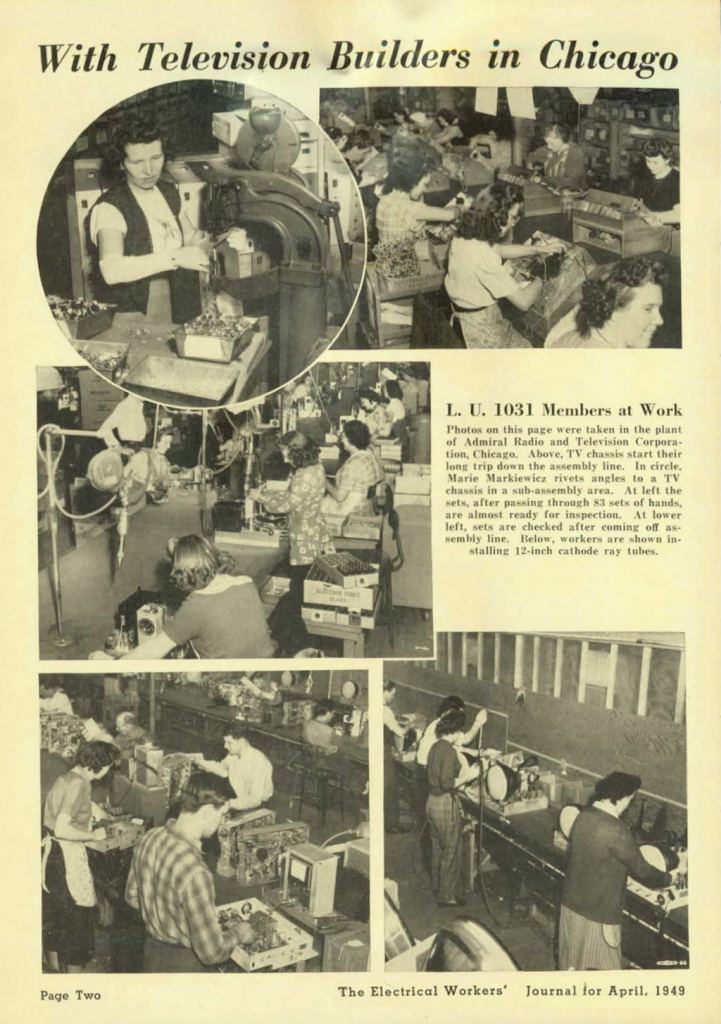

Women filled virtually every available role in the assembly of television sets, save the final calibration of the picture tubes, which required very sophisticated knowledge of electronics and employed some men. Over 80 women would lay hands on each and every television set, doing all of the wiring, soldering, assembly and testing – apparently with much greater reliability and productivity than their male counterparts had a decade before.

Admiral was delighted with their majority-female workforce, which helped them to cut costs and market televisions more cheaply, aiding in their proliferation into American households. However, as women were encouraged by the US government to have children and replenish the population, they gradually left the workforce during the “baby boom” of the 1950s, largely becoming stay-at-home mothers, and not returning.

Admiral was delighted with their majority-female workforce, which helped them to cut costs and market televisions more cheaply, aiding in their proliferation into American households. However, as women were encouraged by the US government to have children and replenish the population, they gradually left the workforce during the “baby boom” of the 1950s, largely becoming stay-at-home mothers, and not returning.

On an assembly line, each worker is responsible for one task involved in the assembly of a product or device. Before the Industrial Revolution, most items were assembled by one individual, from parts they – or a small team of which they were a part – made themselves. However, this was time-consuming and expensive, and methods were found to streamline the manufacturing process, first by specialising workers on particular segments of the production process, and later by more efficiently moving parts and partially-assembled products between them.

The most famous early example of a modern assembly line was at the Ford Motor Company in Michigan. Ford employee William Klann was inspired by his visit to a Chicago slaughterhouse, where carcasses moved along a conveyor belt, and each employee only removed one part. Ford developed an assembly line for its Model T car, which cut manufacturing time significantly.

The most famous early example of a modern assembly line was at the Ford Motor Company in Michigan. Ford employee William Klann was inspired by his visit to a Chicago slaughterhouse, where carcasses moved along a conveyor belt, and each employee only removed one part. Ford developed an assembly line for its Model T car, which cut manufacturing time significantly.

Early television sets were made up of the housing, usually made of wood, a power chassis which provided high voltage for the picture tube and DC (direct current) voltage for other components, a tuner which isolated the signal channel (often part of the channel dial assembly), an audio chassis which decoded the audio signal and amplified it, sending it to a loudspeaker, and a video chassis, which decoded the video signal and drove the various parts of the cathode-ray tube in order to display the image.

A factory was made up of multiple assembly lines, each either manufacturing a component, such as the CRT or the video chassis, and a final line that assembled those components.

Finally, the entire unit would be tested for quality control purposes and any defects troubleshooted and repaired. The finished product would then be packed away for shipping to department stores and retailers.

The efficiency and compartmentalised nature of the assembly line allowed for the “electronics revolution” and the world we live in today.

Be the first to comment