A large, rectangular canvas bag sits in the middle of a huge oaken conference table, a gaggle of journalists assembled around it, while Steve Jobs talks Walkman.

“It’s amazing”, Jobs says, “only about that thick.” He gestures with his thumb and forefinger to describe its width. “The limit was how thin they could make the cassette drive mechanism.”

“It’s amazing”, Jobs says, “only about that thick.” He gestures with his thumb and forefinger to describe its width. “The limit was how thin they could make the cassette drive mechanism.”

Jobs is, of course, attempting to segue into his own innovation, sitting in the canvas bag, but the journalists are impatient, and Jobs quickly surmises that this time, he’s not the object of their affections – what’s in the bag is.

“Let’s not keep you waiting any longer,” he says, flipping open the bag, and pulling out the conclusion of four years of his personal direction, plopping it on the table

He looks for something, and realising where it is he strides over to a side table, picks up a flat plastic square and tosses it uncaringly at the device on the table, which looks like some sort of portable television.

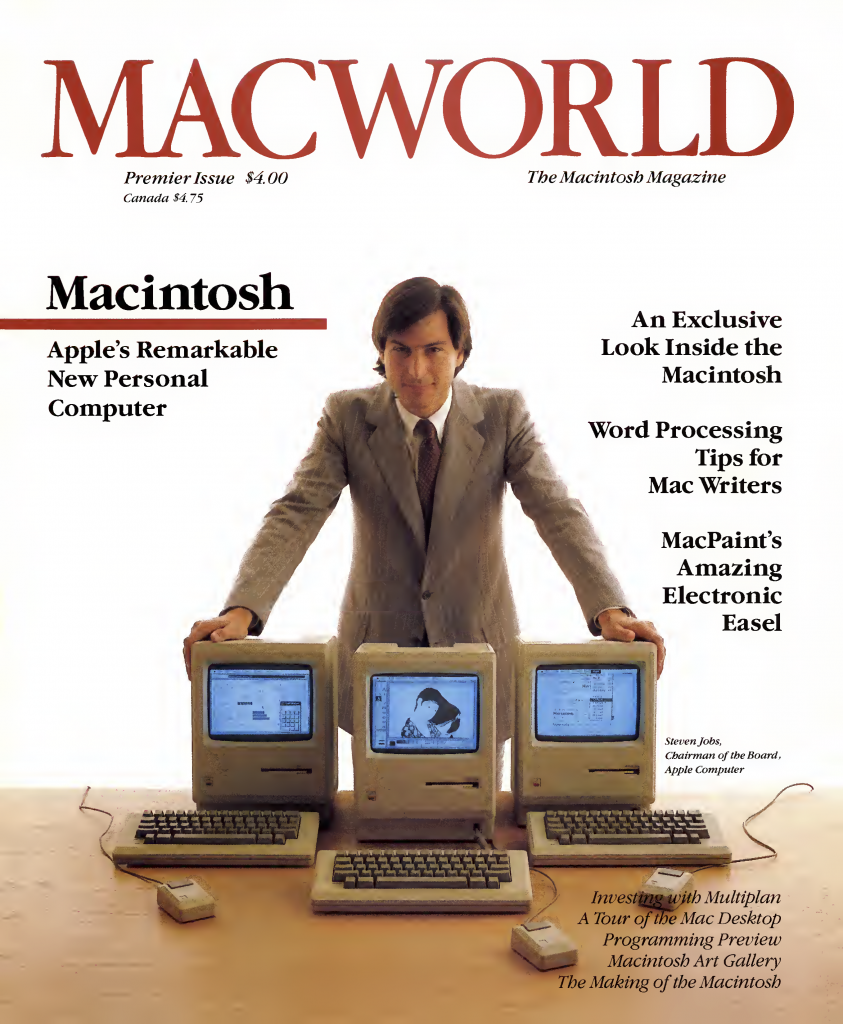

That portable television was the Macintosh, an integrated 16-bit computer, floppy disk drive, and 9-inch (23cm) CRT monochrome display. The year was 1984, and Apple was just about to launch their new product, an all-in-one compact personal computer, an effort to erase the hardware paradigm with the public and leave only software.

“Take it to work during the day, bring it home for the kids at night,” was Apple’s marketing pitch – good for business, great for learning, excellent at anything you could ever want a computer to do, the Macintosh was meant to be the first computer appliance, something that you just plugged in and it worked, with no need to read a complicated technical manual in order to use it.

At one-quarter (US$2500) the cost of the US$10000 Lisa, the Macintosh’s predecessor, Jobs hoped that his machine would become as common as, well, Walkmen. With its sophisticated GUI (Graphical User Interface), he was confident that anyone could learn how to use it, and that everyone who did would swear they didn’t know how they ever got along without it.

At one-quarter (US$2500) the cost of the US$10000 Lisa, the Macintosh’s predecessor, Jobs hoped that his machine would become as common as, well, Walkmen. With its sophisticated GUI (Graphical User Interface), he was confident that anyone could learn how to use it, and that everyone who did would swear they didn’t know how they ever got along without it.

The star of the Macintosh show was arguably its cathode-ray tube display. Sure, the mouse was certainly way up there in the billing, but what good is a mouse if you can’t see anything? The whole box of tricks becomes nothing more than just a very expensive box once you tape a square of cardboard over the screen!

But why build the screen into the computer? Sure, portability is one thing, but couldn’t you just have a monitor at home and a monitor at work? Problem solved! Well, the only problem with that was that monitors in 1984 were largely simple “composite” displays – which were basically just televisions without the ability to tune-in TV stations. They also had the same number of horizontal scan lines, which was fine for the low-resolution output of contemporary 8-bit computers such as the Commodore 64, but insufficient for the GUI of the Macintosh.

For detached monitors to work in the described scenario (work/home) you would need to buy two special Macintosh monitors – that would add a fair amount to the price, and consumers weren’t fond of the idea of buying what many of them saw as a TV which could only be connected to one thing. No, the only way to really resolve the argument was to build the monitor into the computer. You want a Macintosh? This is your screen, period.

For detached monitors to work in the described scenario (work/home) you would need to buy two special Macintosh monitors – that would add a fair amount to the price, and consumers weren’t fond of the idea of buying what many of them saw as a TV which could only be connected to one thing. No, the only way to really resolve the argument was to build the monitor into the computer. You want a Macintosh? This is your screen, period.

Not that that was a bad thing. The newfangled concept of icons (picture representations of real-world objects, such as a pencil or a piece of paper) worked well with the Macintosh’s monochrome high-resolution display, the crisp contrast between its black and white pixels making text stand out like no other computer available at that time could. While other computers had white (or green, or orange) text on a black screen, the Macintosh had black text on a white background, just like a printed book or a newspaper.

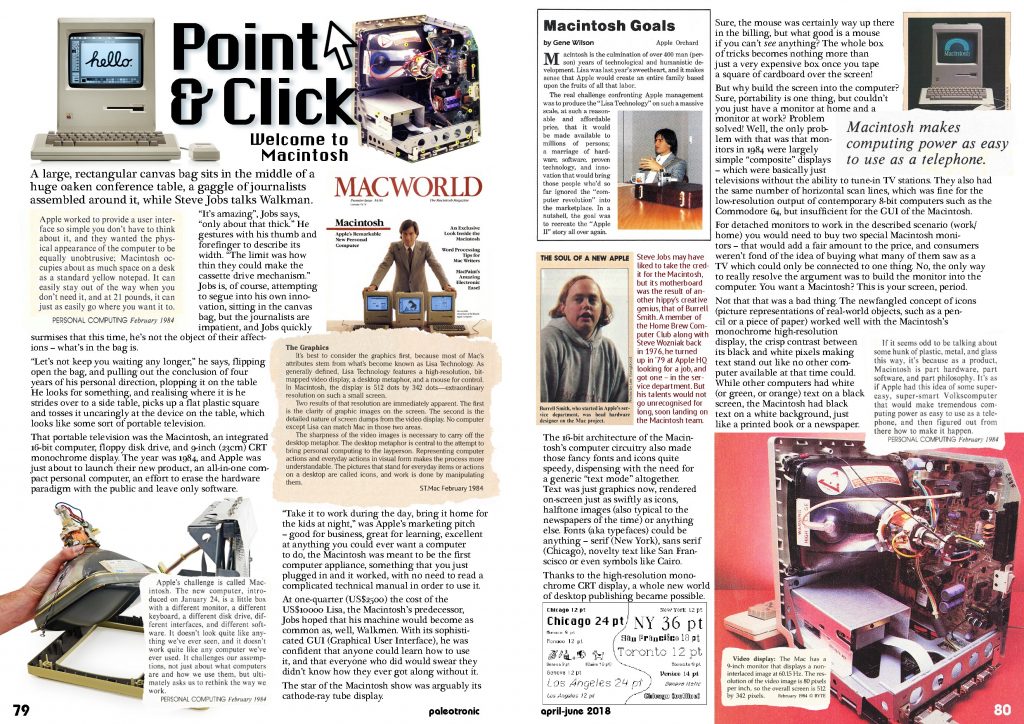

The 16-bit architecture of the Macintosh’s computer circuitry also made those fancy fonts and icons quite speedy, dispensing with the need for a generic “text mode” altogether. Text was just graphics now, rendered on-screen just as swiftly as icons, halftone images (also typical to the newspapers of the time) or anything else. Fonts (aka typefaces) could be anything – serif (New York), sans serif (Chicago), novelty text like San Franscisco or even symbols like Cairo.

Thanks to the high-resolution monochrome CRT display, a whole new world of desktop publishing became possible.

Thanks to the high-resolution monochrome CRT display, a whole new world of desktop publishing became possible.

However, at the Macintosh’s launch, only a dot-matrix printer, called the ImageWriter, was available. While the ImageWriter was fine for home and school use, its print quality was too poor for the publishing industry. Steve Jobs recognised this and negotiated with Adobe Systems to license their PostScript protocol, a vector-based programming language that when combined with a laser printer allowed for the rasterisation of fonts at a high-resolution – visually equivalent to traditional mechanical typesetting.

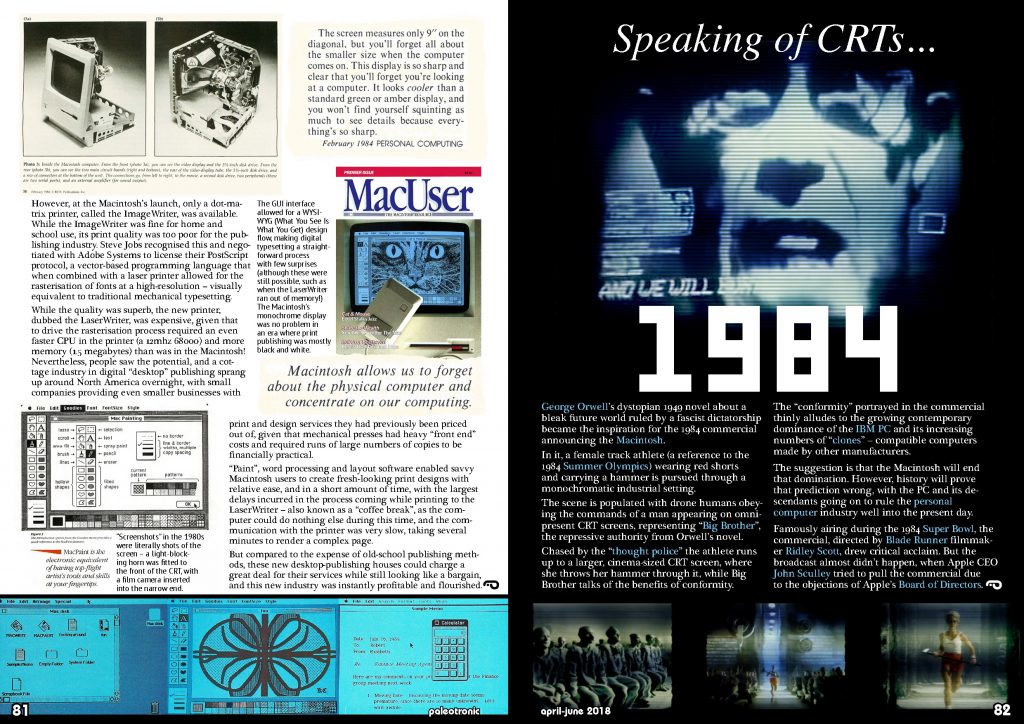

While the quality was superb, the new printer, dubbed the LaserWriter, was expensive, given that to drive the rasterisation process required an even faster CPU in the printer (a 12mhz 68000) and more memory (1.5 megabytes) than was in the Macintosh!

Nevertheless, people saw the potential, and a cottage industry in digital “desktop” publishing sprang up around North America overnight, with small companies providing even smaller businesses with print and design services they had previously been priced out of, given that mechanical presses had heavy “front end” costs and required runs of large numbers of copies to be financially practical.

“Paint”, word processing and layout software enabled savvy Macintosh users to create fresh-looking print designs with relative ease, and in a short amount of time, with the largest delays incurred in the process coming while printing to the LaserWriter – also known as a “coffee break”, as the computer could do nothing else during this time, and the communication with the printer was very slow, taking several minutes to render a complex page.

But compared to the expense of old-school publishing methods, these new desktop-publishing houses could charge a great deal for their services while still looking like a bargain, and this new industry was instantly profitable and flourished.

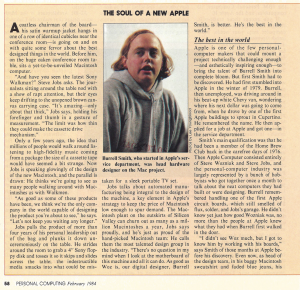

Steve Jobs may have liked to take the credit for the Macintosh, but its motherboard was the result of another hippy’s creative genius, that of Burrell Smith. A member of the Home Brew Computer Club along with Steve Wozniak back in 1976, he turned up in ‘79 at Apple HQ looking for a job, and got one – in the service department. But his talents would not go unrecognised for long, soon landing on the Macintosh team.

Steve Jobs may have liked to take the credit for the Macintosh, but its motherboard was the result of another hippy’s creative genius, that of Burrell Smith. A member of the Home Brew Computer Club along with Steve Wozniak back in 1976, he turned up in ‘79 at Apple HQ looking for a job, and got one – in the service department. But his talents would not go unrecognised for long, soon landing on the Macintosh team.

George Orwell’s dystopian 1949 novel about a bleak future world ruled by a fascist dictatorship became the inspiration for the 1984 commercial announcing the Macintosh.

In it, a female track athlete (a reference to the 1984 Summer Olympics) wearing red shorts and carrying a hammer is pursued through a monochromatic industrial setting.

The scene is populated with drone humans obeying the commands of a man appearing on omnipresent CRT screens, representing “Big Brother”, the repressive authority from Orwell’s novel.

Chased by the “thought police” the athlete runs up to a larger, cinema-sized CRT screen, where she throws her hammer through it, while Big Brother talks of the benefits of conformity.

The “conformity” portrayed in the commercial thinly alludes to the growing contemporary dominance of the IBM PC and its increasing numbers of “clones” – compatible computers made by other manufacturers.

The suggestion is that the Macintosh will end that domination. However, history will prove that prediction wrong, with the PC and its descendants going on to rule the personal computer industry well into the present day.

Famously airing during the 1984 Super Bowl, the commercial, directed by Blade Runner filmmaker Ridley Scott, drew critical acclaim. But the broadcast almost didn’t happen, when Apple CEO John Sculley tried to pull the commercial due to the objections of Apple’s Board of Directors.

Be the first to comment