I GREW UP WITH THE TUBE FOR A NANNY.

My day would start with Sesame Street, The Great Space Coaster, Reading Rainbow, Mister Rogers… and then later in the afternoon, trashy cartoons such as The Smurfs, He-Man and She-Ra, Scooby Doo and the Flintstones. In black-and-white at first, then colour, the Tube educated, informed and entertained, and frequently suggested what I should be eating for breakfast (which thankfully I never did, thanks Mom!)

During prime-time the family sat around the Tube and played games with Vanna White and Alex Trebek, said good-bye to M*A*S*H, found out who shot JR, saw Hulk Hogan team up with the A-Team to beat the bad guys, and helped fight famine with Band Aid.

The Tube wasn’t just for television, either. It also helped me explore the world of early home computing, at first with a Sinclair ZX81, then a Tandy MC-10, a Commodore 64, Atari 130XE, Atari 520ST… and at school Apple IIs and Macintoshes. Oregon Trail and M.U.L.E. and Jumpman and Impossible Mission; Dark Castle, Shufflepuck Cafe, Marble Madness and Stunt Car Racer. Never mind various video-game consoles!

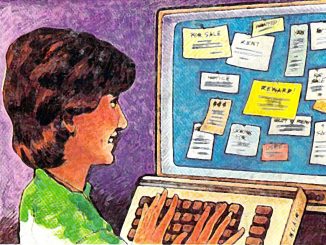

But it wasn’t all fun and games – computer programming, word processing and early graphic design (Print Shop and The Newsroom) occupied much of my childhood, as did telecommunicating through bulletin-board systems and navigating early networks such as Tymnet to connect to on-line services such as CompuServe.

It seemed as if I could do anything and go anywhere through the Tube. Televised documentaries took me to ancient Greece and medieval Britain, back to the American Civil War and forward to the 21st century and flying cars (by the way, where’s my hoverboard?) Videodiscs and VCRs brought the cinema home, cable television launched 24-hour news and made the music video an art form. Meanwhile, millions used the Tube for work, filling out spreadsheets and calculating complex mathematical formulas, running businesses and making new scientific discoveries. The Tube would provide visual feedback for medical diagnostic and car troubleshooting equipment, act as monitors for closed-circuit security cameras, put the scope in oscilloscope and make critical radar and sonar information immediate and obvious.

The Tube was everywhere, and its influence over western society would only continue to grow toward the end of the 20th century, as multiple-television households, computers and video-game consoles became increasingly more commonplace, until being fully replaced by LCD displays in the early 21st. I can’t imagine what the world would have been like without the Tube – or maybe I can.

What if the cathode-ray tube had never been invented? John Logie Baird’s mechanical television would’ve ruled the video airwaves unchallenged – or would it have? Mechanical televisions were finicky, fussy things, and the “flying spot scanner” that acted as a camera by illuminating and broadcasting a scene in progressive little chunks (see Gadget Graveyard for more explanation) only worked in total darkness, making programme production difficult, and was fixed in place, unable to pan, zoom or do anything we expect from a traditional camera. Of course advances in mechanical television would have likely been made, and were – for example, early colour television cameras were actually fancy monochrome “flying spot” scanners with mechanical spinning tinted plastic wheels to record colour. But even these used a really bright CRT to create the light for the scanning spot, replacing large, hot arc lights that made early television studios really uncomfortable places to be.

These issues make it hard to say if mechanical television would have ever taken off. Would the general public have ever seen it as more than just a curiosity, a fancy toy for people with the technical sense to keep their equipment in perfect working order, or would it have evolved into something straightforward enough for adoption by “the common man”? If so, I suspect most television programs would’ve been filmed on 16mm movie cameras, then “scanned” using some sort of telecine device; perhaps there still would’ve been All In The Family and Cheers and MacGyver – even in colour, just at 16 frames per second, on a much smaller screen, and with a motor constantly humming in the background. Or would the neighbourhood movie house have survived, with families continuing to make nightly pilgrimages to see the latest newsreels, shorts and features, maybe even well into the 1990s when LCD projectors and panels (presumably) would have eventually, finally launched the “personal screen revolution”?

Alternatively, 8mm film could’ve become the CRT-free world’s videotape, with rental stores providing low-quality reels of movies out of the cinemas, and current events programmes such as weekly news updates. Either way, while the age of “live” video wouldn’t have happened, I think society would have found a way to survive. After all, immediacy would’ve still been found through radio, or perhaps cable subscription audio programming or “broadcast” telephony.

Computing, however, is another matter entirely. Without video monitors, output would remain constrained to arrays of light-emitting diodes or paper printouts. Could you imagine word processing where you entered and edited your document on paper, to only then output the finished document also on paper? You’d go through an awful lot of ink and dead trees! And I hope you like text adventures, because that’d be the most advanced computer entertainment you’d be likely to get. At least until the world ran out of oxygen after cutting down all the trees just so you could GET LAMP.

Maybe that’s hyperbole – maybe not. The world certainly would have been different though, no argument there. Those medical and automotive diagnostic monitors would’ve bleeped and blooped and provided cash register-style printouts instead of video, technicians would’ve needed to learn to identify signals by how they sounded and not how they looked. Security guard would’ve been a popular occupation, with scores of them patrolling stores and public areas, monitoring the populace with eyeballs instead of cameras and video screens.

Or instead of security guards, they may have been government agents – after all, without the Tube to provide immediate feedback for radar systems, World War II could have ended much differently. I don’t know – I don’t have a crystal ball. But I did have the Tube. And while it’s had some poorer moments, it’s hard not to agree that, overall, the Tube was good.

The second issue of Paleotronic, its articles rolled out on the website over the next several weeks, is a celebration of the Tube – we’ll explore the invention of the Tube, how it won the television war between Baird and a farm boy named Farnsworth, gave birth to the video-game industry, revolutionised computing and so much more. We’ll look at common CRT-related problems and typical repairs, learn the difference between vector and raster graphics, discover how to generate a colour video signal, and find out about obscure applications of the Tube such as slow-scan amateur television. So power up, tune in and turn on, because for this issue the medium really is the message.

All hail the Tube.

Be the first to comment