While Asian manufacturers were feverishly working on perfecting videotape, American RCA was working on a videodisc system – not a laserdisc system, which did not contact the surface of the disc, but instead a system similar to a phonograph record, where a needle sat in a groove carved into the disc.

RCA first began researching a method of recording video on to a disc in 1964, however they didn’t devote a lot of resources to it and with only four people working on it development was slow. But by 1972 the team had produced a prototype disc system capable of holding 10 minutes of colour video.

RCA first began researching a method of recording video on to a disc in 1964, however they didn’t devote a lot of resources to it and with only four people working on it development was slow. But by 1972 the team had produced a prototype disc system capable of holding 10 minutes of colour video.

The system worked by making the disc conductive – that is, electricity could pass through it. The video signal is stored on the disc by varying the depth of the grooves to correspond to the waveform of a frequency-modulated (FM) video signal – similar to a broadcast television signal. A diamond stylus sits in the groove, a metal electrode attached to it. The capacitance (that is, the amount of electrical charge necessary for current to pass from the disc to the electrode) is measured, and because this varies based on the depth of the stylus in the groove (the higher it is the more charge is required) a signal can be reconstructed.

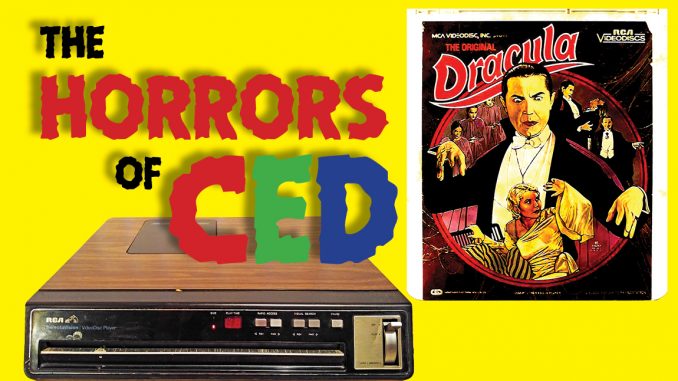

This system was dubbed ‘Capacitance Electronic Disc’ or CED.

However, because there is physical contact between the stylus and the disc, both the grooves and the stylus can wear over time, similarly to vinyl records. As with records, if they wear too much they can ‘skip’, which is an even less desirable event when watching the climax of a movie! RCA attempted to solve this by constructing a complicated layered disc made of a vinyl substrate, a layer of nickel, an insulation layer and finally a top layer of silicone but this did not entirely solve the issue of stylus or disc wear, and so it was decided to make the system cheaper to manufacure and sell, so that discs and stylii would be cheaper to replace, should they wear out.

As such, the final video discs were made of PVC, blended with carbon to make them conductive, and then coated with a thin layer of silicon lubricant. However, there was still another problem: originally, RCA executives had imagined that the videodiscs would be packaged and sold similarly to vinyl records, with the disc in a sleeve that would be removed by the user and placed in the player, like with LaserDisc. However, particles of dust and fingerprints were gigantic in comparison to the tiny grooves in the videodisc, and could easily cause playback to ‘skip’. A dusty disc could skip hundreds of times during playback, shortening a 90 minute movie to 30 seconds – not the sort of edit the director had in mind.

As such, the final video discs were made of PVC, blended with carbon to make them conductive, and then coated with a thin layer of silicon lubricant. However, there was still another problem: originally, RCA executives had imagined that the videodiscs would be packaged and sold similarly to vinyl records, with the disc in a sleeve that would be removed by the user and placed in the player, like with LaserDisc. However, particles of dust and fingerprints were gigantic in comparison to the tiny grooves in the videodisc, and could easily cause playback to ‘skip’. A dusty disc could skip hundreds of times during playback, shortening a 90 minute movie to 30 seconds – not the sort of edit the director had in mind.

Even if you cleaned the disc before putting it in the player, dust that had settled on it earlier could have absorbed moisture from the air and effectively cemented itself into the groove, becoming impossible to remove and making the disc skip permanently.

So a ‘caddy’ system was devised that kept the discs in a protective plastic cover, unexposed to dusty environments and untouched by human hands. The sleeve was inserted into the player, which could unlock the inner caddy holding the disc and keep it in place while the sleeve was removed. To attempt to mitigate any dust that might have settled on the disc if and while it was left in the player (something owners were warned not to do!) the sleeves often contained strips of felt that brushed the disc as it was inserted and removed.

The caddy became a selling point, as parents could be comfortable with their children using the player, as it was hard to damage the disc.

And this was a good thing because kids would need to handle the discs a lot. While RCA had managed to increase the amount of video that could be stored on a single side of the disc to an hour, this meant that almost every movie needed to be stored on both sides of the disc. Halfway through playback, the viewer would need to ‘flip’ the disc, by inserting the caddy, withdrawing it, turning it over, inserting it again and removing it again! This was time consuming and annoying.

If the movie was more than two hours long you would need to insert a second disc to finish it. And often, users would put the wrong side of the sleeve in, meaning that if you thought you were inserting side one, you could end up starting to play side two – spoilers! Although, children could (and did) insert sandwiches and all sorts of other things into VCRs, so the annoyances could be forgiven, at least for the certainty that foreign objects were unlikely to end up either on the disc or in the player.

RCA released its first videodisc player on early 1981 – 17 years after it started to research the idea. Unfortunately, all of that time spent messing about would quickly doom the format.

CED had initially been scheduled for release in 1977, a time when it would have had almost no competition from tape, but the discs were only able to hold 30 minutes at that point, and the discs themselves were not robust. And so the release was delayed for four years.

While videotape players had been expensive through the late 1970s, their costs had gradually come down over that time. Although the videodisc player was still cheaper than a VCR (by over a third), a used VCR could be had for the price of a new CED player by the time CED was released. RCA attempted to compensate for this by releasing discs cheaper than their videotape versions – a videotape could cost US$50 while the videodisc may cost $25-30 – but rental stores often charged the same to rent both, and since most people rented movies rather than buying them there was no benefit to the CED.

And speaking of renting, not very many stores stocked CEDs, and those that did didn’t typically have anywhere near the selection of what they had on tape (even though some 1700 NTSC titles were released, although many of those were episodes of TV shows). Some rental outfits complained about the finicky nature of the machines and the potential for customers to damage the disks by leaving them in the machines and/or smoking around them. Demand for CED players dropped and discounting began. Department stores began to drop them from their inventory.

And speaking of renting, not very many stores stocked CEDs, and those that did didn’t typically have anywhere near the selection of what they had on tape (even though some 1700 NTSC titles were released, although many of those were episodes of TV shows). Some rental outfits complained about the finicky nature of the machines and the potential for customers to damage the disks by leaving them in the machines and/or smoking around them. Demand for CED players dropped and discounting began. Department stores began to drop them from their inventory.

Although you didn’t have to rewind a CED, you couldn’t see the screen while seeking on most players either – something you could do with a VCR, and yet another advantage of tape that CED owners lusted after. CED simply became a stepping stone to VHS for most people – once the price of VHS VCRs dropped sufficiently enough, the CED player found itself replaced, and languishing in a basement or a garage, forgotten.

Although you didn’t have to rewind a CED, you couldn’t see the screen while seeking on most players either – something you could do with a VCR, and yet another advantage of tape that CED owners lusted after. CED simply became a stepping stone to VHS for most people – once the price of VHS VCRs dropped sufficiently enough, the CED player found itself replaced, and languishing in a basement or a garage, forgotten.

As Radio Electronics said, “The varying capacitance that results (from the varying depth of the groove) is then coupled to a 910MHz tuned line in the resonator assembly that is driven by a 915Mhz oscillator. The changing capacitance modulates the resonant frequency of the 910Mhz tuned line, thus changing the operating point of the 915Mhz oscillator energy on the tuned line. This in turn amplitude modulates the 915Mhz oscillator signal. The modulated 915Mhz signal is then applied to a peak detector circuit. The signal recovered by peak-detecting the oscillator signal is an electrical replication of the information (contained) in the grooves of the videodisc.” Whew!

Basically, the changing capacitance slightly altered the frequency of a carrier, which was then used to change the amplitude of a third 915Mhz wave, creating an amplitude modulated signal. This signal itself contains both the audio and the video signals (luminance or brightness, and chrominance or colour) which are each then demuxed from it. However, in most players these signals were then passed to an RF modulator, which combined them all back into a TV signal.

Although models featuring stereo sound, infrared remote controls and random access capabilities appeared in 1982-83, they still couldn’t record, and uptake remained limited.

Despite aggressive discounting and giveaways of free discs, in early 1984 it became obvious RCA’s ambition of having CED in 50% of American homes by the following year wasn’t going to happen, and recognising that the system was never going to be profitable RCA announced that they were discontinuing the production of new players in April.

Some CED enthusiasts began to hoard discs and so RCA decided to continue to manufacture them for three more years, but stopped after two as demand had dwindled to almost nothing by that point. The last disc produced was a documentary about the history of CED called ‘Memories of Videodisc’, released in 1986.

Despite its kid-friendly nature, superior video quality when compared to standard VHS and the disc’s general robustness in comparison to tape, CED was inferior to LaserDisc and couldn’t record like VHS, and thus was doomed to be quickly dispatched by its competitors, to become a curiosity of electronic history.

My personal experience

My family bought a Toshiba CED player on sale in 1982 or 83. We weren’t the only ones we knew, either – we lived in a less-affluent part of our city and there were several neighbours that took advantage of the low-cost of the CED system. After all, it was the early 1980s and the ability to play video at home was a novelty previously only afforded to those in much higher tax brackets!

We rented discs while they were available, and bought a few as well (including Planet of the Apes and Sunset Boulevard, each of which I must have seen dozens of times, and which reflected the large percentage of CED movies drawn from films studios were no longer making much of a profit from, and thus demanded low royalties from their distribution.

But despite the age of some of our movies, it was still magical seeing them on our TV, on demand.

The CED player gave us a glimpse of the future that was to come, one where you wouldn’t be a slave to a schedule when it came to visual entertainment, a future where you could just pick up a movie and pop it into the CED player, or VCR, or DVD player, or Blu-Ray player or Netflix app. And it gave that glimpse to working-class kids who may not have even seen a videotape player at school by that point (static film strips played along to a record were still a thing then, and if you were lucky a couple times a year you got to watch a 16mm movie!)

But of course, when an affordable VCR happened along we jumped on it. It was ‘better’.

However, despite these downsides, it was still pretty cool you could watch a movie with what was, in effect, a record player. Sadly though, once they were discontinued it became hard to get movies, stylii, parts or find someone to repair them, and they quickly vanished from society, lost to time.

Be the first to comment