Imagine you forked over US$30 (US$80 in 2018) or even more in Australia with its ‘luxury’ import tax for an ET cartridge to give little Johnnie for Christmas and he hated it! You would’ve been totally over this whole videogame thing. But what else was little Johnnie (or Janie) going to do with their time? How about a home computer?

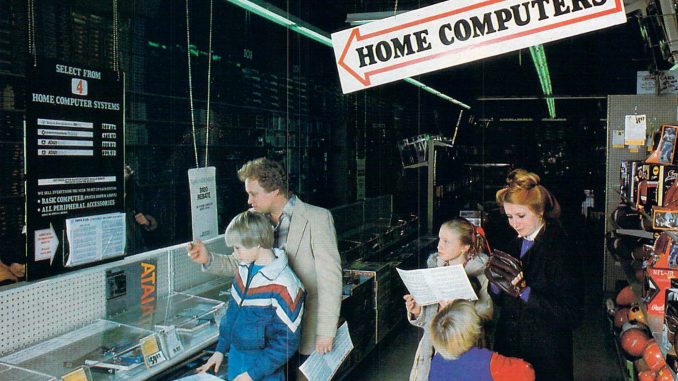

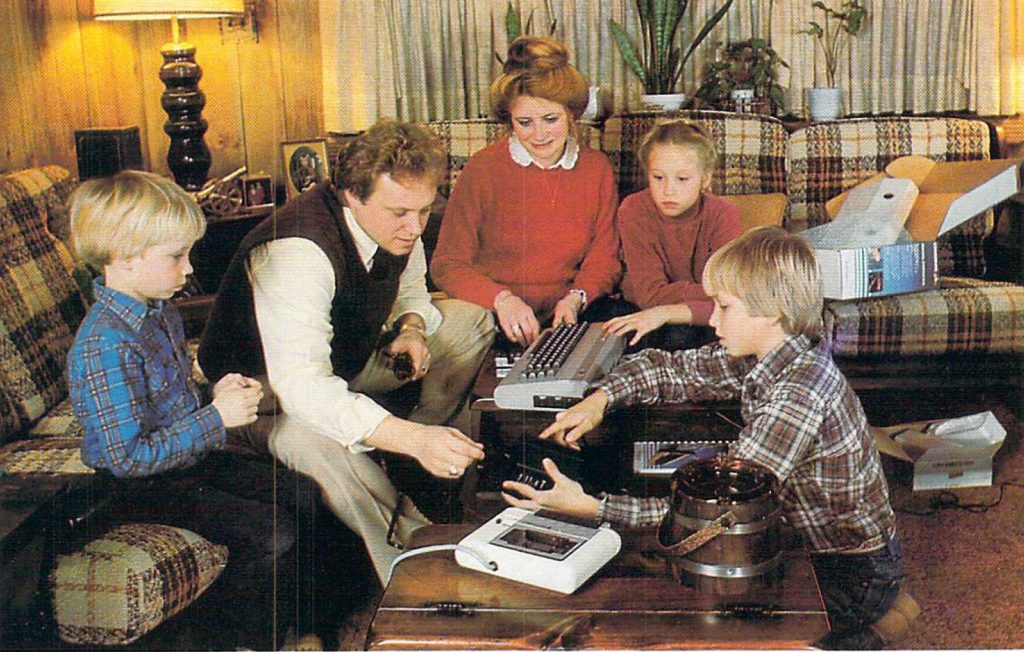

During the late 1970s home computers had made the same technological advances videogame consoles had, with colour graphics, improved sound and features such as joystick controllers. In the early 1980s software developers realised there was enough of a market to write games for them, and parents began to see them as a viable alternative to videogame consoles.

There’s so much more the family can do with a home computer! You can balance your chequebook, write letters, go on-line, learn spelling and math – and play games, of course, but only after homework is done…

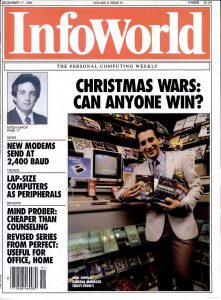

And after the fiasco of the previous Christmas, Santa didn’t really need all that much convincing to try something else. 1983 had seen an explosion of home computer models of varying capabilities and at various price-points – however, the question on everyone’s minds was not who was going to win, but who would survive.

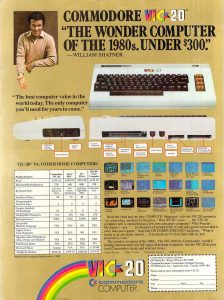

Commodore’s Jack Tramiel saw an emerging market for low-cost home computers, releasing the VIC-20 in 1980. At a US$299 price point sales were initially modest, but rival Texas Instruments, making a play for the bottom of the market, would heavily discount its TI99/4A, and start a price war with Commodore that culminated with both computers selling as low as $US99. Only one company was going to walk away.

Commodore’s Jack Tramiel saw an emerging market for low-cost home computers, releasing the VIC-20 in 1980. At a US$299 price point sales were initially modest, but rival Texas Instruments, making a play for the bottom of the market, would heavily discount its TI99/4A, and start a price war with Commodore that culminated with both computers selling as low as $US99. Only one company was going to walk away.

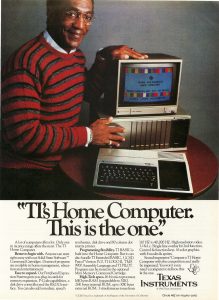

In 1979 microchip and calculator manufacturer Texas Instruments had introduced the TI99/4, its first attempt at entering the emerging home computer space. While it was the first 16-bit home computer, its US$1150 price was higher than even the Apple II, and with a small software library in comparison to competitors, retailers struggled to sell it. Two years later, in 1981, TI released the 99/4A, which improved the keyboard widely criticised in its predecessor, but it still failed to attract the attention TI thought it deserved. Management decided that if they could just get the computer into the hands of users, a presumably positive response would spread by word-of-mouth, and sales would improve as a result. And so TI not only dropped the price of the 99/4A all the way down to the US$299 price of the VIC-20, they offered an additional $100 rebate.

But while TI spokesperson Bill Cosby joked about how easy it was to sell a computer when you gave people US$100 to buy one, Jack Tramiel wasn’t going to take this lying down, and he dropped the price of the VIC-20 to US$200 in order to match TI. However, unlike TI, who was selling the 4A at a loss in order to gain market share, Commodore wasn’t losing any money at all, since it owned MOS Technology, the maker of many of the chips inside of the VIC-20, and as a result got all of those components at cost. Meanwhile TI was paying full price and haemorrhaging cash on every model sold.

You would think TI might have realised they were playing a fool’s game and back off but instead after Tramiel dropped the wholesale price of the VIC-20 to US$130 they went all-in, dropping the 4A’s retail price to $150. Commodore went to $100, and TI matched it, with many retailers selling both machines for $99. Inside TI, Cosby’s joke stopped being funny, and many wondered whether management had dug them into a hole they could never climb out of.

After losing over US$100 million in the third quarter of 1983 alone, TI pulled the plug. They dumped their stock of the 4A, selling the computer for $49 but even at that price nobody wanted it; the public had already concluded at the US$99 price point that there was likely no future for it, having previously learned that discontinued computers typically languished without new software.

After losing over US$100 million in the third quarter of 1983 alone, TI pulled the plug. They dumped their stock of the 4A, selling the computer for $49 but even at that price nobody wanted it; the public had already concluded at the US$99 price point that there was likely no future for it, having previously learned that discontinued computers typically languished without new software.

The TI99/4A was counted out, the VIC-20’s arm was raised and the match was over. But TI wasn’t the only company who wanted to try their contender in the ring. There was also Coleco, and Tandy.

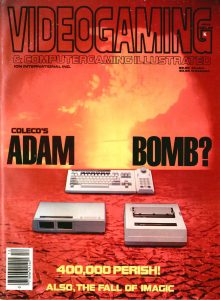

Coleco had entered the videogame console market late, introducing the Colecovision in mid-1982 just as Atari was beginning to wear out its welcome with the public. With its superior graphics and sound, and Donkey Kong as its pack-in game, it sold well before Christmas, but was not immune to the plague ET subsequently cursed the industry with and when Coleco management saw consumer sentiment was turning toward home computers they saw an opportunity to jump trains. The marketing department decided their ideal customer was parents of less-technically savvy teenagers who needed to do school assignments and wanted to play arcade conversions, and so they suggested adding a printer, keyboard and tape storage to the existing Colecovision console, rather than develop an entire new machine. It was hoped this could get the computer, christened the Adam, to market faster, but adding all those peripherals was trickier than expected, and despite promises to retailers Coleco failed to deliver most of the units in time for Christmas – and many of those they did deliver were defective. Poor reviews and disappointed potential customers coloured public sentiment and the Adam bombed, taking the Colecovision with it.

After 1984 delivered heavy losses, Coleco discontinued both products by mid-1985.

Tandy also tried to get into the action, releasing a cost-reduced version of its Color Computer, the MC-10. Modeled after the Sinclair ZX81, the MC-10 had a small form-factor and a chiclet keyboard with a similar BASIC entry format. But it wasn’t compatible with most Color Computer software and Tandy released only a few MC-10 programs. The net result is the MC-10 bombed.

After all the dust had settled, the only real winner was Commodore. It fended off all of its competitors and cemented the Commodore 64 as the low-budget 8-bit computer everyone wanted their parents to buy.

But while home computers had beaten video-game consoles down, they weren’t entirely out, and were destined to come back with a vengeance. In the late 1980s, computer manufacturers failed to convince many of their customers to upgrade to 16-bit models, who found their 8-bit computers still sufficient for their productivity needs, while their children were more interested in the new wave of video-game consoles, the Nintendo NES and the Sega Master System, which provided arcade conversions and platform games, some unavailable even on 16-bit computer systems.

But while home computers had beaten video-game consoles down, they weren’t entirely out, and were destined to come back with a vengeance. In the late 1980s, computer manufacturers failed to convince many of their customers to upgrade to 16-bit models, who found their 8-bit computers still sufficient for their productivity needs, while their children were more interested in the new wave of video-game consoles, the Nintendo NES and the Sega Master System, which provided arcade conversions and platform games, some unavailable even on 16-bit computer systems.

Parents ended up buying those instead.

Be the first to comment