While the Internet would eventually bring computer-based telecommunications to the masses, by the late 1980s more tech-savvy individuals were already meeting new people and having all sorts of discussions ‘on-line’ – and in some cases had been for almost a decade. While most of them were adults, plenty of them were children, and some of those would become life-long friends.

In the late 1970s most people didn’t have any real way to engage in one-to-many discussions outside of school classrooms, work meetings or family dinners. And getting information about specific topics could be a tedious process of calling seemingly random phone numbers and speaking to random people who were almost always unhelpful. Bulletin-board systems created networks of people (often with similar interests) who could easily solicit information from each other, keep themselves informed about current events and discoveries, and engage in debate – uncommon activities for the general public.

In the late 1970s most people didn’t have any real way to engage in one-to-many discussions outside of school classrooms, work meetings or family dinners. And getting information about specific topics could be a tedious process of calling seemingly random phone numbers and speaking to random people who were almost always unhelpful. Bulletin-board systems created networks of people (often with similar interests) who could easily solicit information from each other, keep themselves informed about current events and discoveries, and engage in debate – uncommon activities for the general public.

‘Dial-up’ access terminals had been a common feature of mainframe computers since the 1960s – a remote office would have a ‘dumb terminal’ connected to a modem that could be used to log into a corporate mainframe across town or in another city. But into the 1970s small hobbyist computers began to appear, capable of running local programs while still connecting to larger systems. But it didn’t take long for owners of these computers to begin to consider whether they could be a ‘host’ themselves, rather than just a client.

Ward Christensen and Randy Suess were two such individuals. During a blizzard in Chicago in January 1978, they wrote a program for their homemade S-100 (Altair-based) computer that would allow a single user to connect to it over a modem and exchange messages with other users. Then that user would disconnect (willingly or unwillingly, if their allotted time was exhausted) allowing another to log-on.

The pair worked on the system for about a month and then made it available for users to dial-in to. They called their invention a “computerised bulletin-board system” or CBBS, the idea being that it was like a push-pin bulletin-board in a supermarket or office, where anyone could tack up a message. But unlike a conventional bulletin-board, users could reply to messages in ‘threads’, sometimes engaging in long, complex discussions taking place over days, weeks or even months.

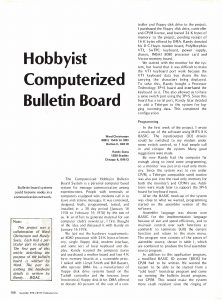

Ward and Randy, known as the ‘system operators’ could watch users as they read and posted messages, and chat with them if they so desired. They were also responsible for moderating discussion – which could sometimes get heated! In late 1978 they described the operation of their CBBS in Byte Magazine, inspiring a number of other individuals to write bulletin-board software of their own. Bulletin-board systems (shortened to BBS) then began to spring up all over!

Over time, the functionality available in BBS software (and consequently to BBS users) began to expand to include features such as private electronic mail, file downloads and games (often known as ‘doors’ as these were often separate applications that the user would ‘open the door and walk in to’, although sometimes doors could be things like horoscope or other text-based application programs). Games also began to appear that accounted for multiple users, including turn-based games such as chess, and games with score leaderboards.

BBSes began to differentiate themselves by specialising into different niches – much like modern-day ‘community’ websites. You might have a BBS in your city entirely devoted to discussions of Christianity – or Dungeons & Dragons. Some were dedicated to particular computing platforms, such as Commodore or Atari, while others might be targeted towards writers, archery enthusiasts, or professional sports fans.

Some even offered crude pornographic material and pirated software.

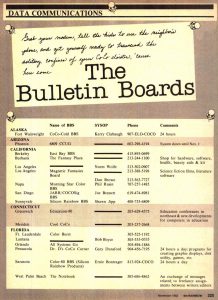

Who ya gonna call? You’ve bought your shiny new modem, but then you’ve discovered you don’t know any bulletin-board phone numbers! Frustratingly for some, BBSes were often only advertised on other BBSes! Most cities had volunteers that managed lists of active BBSes, but once again these lists were usually distributed exclusively on BBSes. So, you needed the number to at least one BBS in order to get started – where could you get one?

Who ya gonna call? You’ve bought your shiny new modem, but then you’ve discovered you don’t know any bulletin-board phone numbers! Frustratingly for some, BBSes were often only advertised on other BBSes! Most cities had volunteers that managed lists of active BBSes, but once again these lists were usually distributed exclusively on BBSes. So, you needed the number to at least one BBS in order to get started – where could you get one?

Well, asking at the local computer shop could be fruitful – assuming it wasn’t selling subscriptions to paid online services, in which case the only numbers it was going to give you would be for CompuServe or The Source. But they might hook you up with a local computer users’ group, and there you’d be certain to get a few BBS numbers.

However, as great as BBSes were, in those days you could only run one program on a computer at a time – which meant that if you were running a BBS, you weren’t able to use your computer for anything else! So, at least in the early days, many people ran their BBSes only in the evenings, so they would continue to have use of their computer during the day. Office computers could also be co-opted and used to run BBSes during off-hours – sometimes the BBS would be related to the business, but occasionally employees would operate their own personal systems.

Over time, people upgraded their computer systems and their old system could be tasked to run BBS software full-time. But this also meant paying for a second telephone line to be installed, along with monthly fees – this could turn into an expensive hobby quite quickly. As modem transmission speeds improved you also needed to upgrade your modem in order to keep your users happy – some cities had a dozens of BBSes or more, and they could be very competitive, constantly upgrading with new BBS software or games in order to attract new users and keep the ones they already had.

So you’d like to start a BBS? You and everyone else! The fact that almost anyone could be a potential sysop meant that practically everyone saw themselves as a potential sysop – BBSes sprang up like weeds. But they often fell right back down just as quickly, their sysops tiring of dealing with difficult users, maintaining BBS databases, acting as mediators, fixing broken hardware or just simply being unable to use their computer during ‘BBS hours’.

So you’d like to start a BBS? You and everyone else! The fact that almost anyone could be a potential sysop meant that practically everyone saw themselves as a potential sysop – BBSes sprang up like weeds. But they often fell right back down just as quickly, their sysops tiring of dealing with difficult users, maintaining BBS databases, acting as mediators, fixing broken hardware or just simply being unable to use their computer during ‘BBS hours’.

And the recurring cost of the telephone line, new BBS software, new modems and so forth were fatiguing to the pocketbook. But this also meant it was hard to get users to invest their time in new BBSes, afraid that their discussions could disappear tomorrow once their sysops realised what they had signed themselves up for. So over time users gravitated towards established BBSes, their confidence in their continued existence relatively equal to the length of time the BBS had been online.

So aspiring sysops needed a ‘hook’ – this could be illicit ‘warez’, but it could also be a new game or multiline chat system software. The occult and anarchism were also popular topics for new BBSes, their owners hoping that hosting contraversial subject matter would intrigue potential users and overcome their misgivings. As a result, the world of bulletin boards could be a rather colourful place.

But as the 1980s progressed the average age of a bulletin-board user dropped. While computers and modems in the 1970s were typically the domain of older professional adults, the marketing of home computers towards adolescents meant that many children soon had access to and became users of BBSes, creating potential concerns that predators could use them to ‘groom’ potential victims.

System operators (known as Sysops) began to talk amongst themselves about users’ behaviour, attempting to organise some measure of community self-policing and pre-empt potential problems before they occurred. This frequently met with mixed success.

To make things even more complicated, some Sysops were bad actors themselves, using their bulletin-board systems for illicit activities such as selling drugs or stolen merchandise. Some offered copyrighted software or XXX-rated material for download – for a fee.

Teenagers also started to operate their own bulletin-board systems, often offering downloads of pirated games and pornography themselves, but usually not for money – which caused friction with those who did. Teenage antics also extended to hacking and ‘phone phreaking’ – the use of specialised electronics to manipulate the telephone system in order to make free long-distance calls (something that was expensive in the 1980s). They also distributed ‘taboo’ texts amongst themselves, such as the Anatchists Cookbook, a tome that described bomb-making along with many other unsavoury activities, under the guise of freedom of information.

Teenagers also started to operate their own bulletin-board systems, often offering downloads of pirated games and pornography themselves, but usually not for money – which caused friction with those who did. Teenage antics also extended to hacking and ‘phone phreaking’ – the use of specialised electronics to manipulate the telephone system in order to make free long-distance calls (something that was expensive in the 1980s). They also distributed ‘taboo’ texts amongst themselves, such as the Anatchists Cookbook, a tome that described bomb-making along with many other unsavoury activities, under the guise of freedom of information.

Indeed, teenagers involved with BBSing were frequently libertarian in their ideologies, unsurprising given the ‘wild west’ nature of that environment, outside of which most young people felt powerless, trapped within the regimented political and social structures of the 1980s and a system of government most young people couldn’t hope to understand.

It’s no surprise they often wanted to be Sysops. Many bulletin-board systems started off in teenagers’ bedrooms, their home computers (sometimes covertly) turned into late-night destinations for other teenagers. But callers couldn’t be trusted to only try inside posted hours, and parents would often receive daytime phantom phonecalls.

Eventually parents would become annoyed to the point they would force their teenager to get their own phone line, but then they would often have to chase them to pay for it. (Sorry Dad!)

And so, in this realm that was largely unpoliced by external forces, teenagers acted out, engaging in all sorts of anti-establishment behaviour and creating the first digital counter-culture. But unlike other youth counter-cultures of the past, adults were not entirely shut out – ‘young adult only’ BBSes were often only so because they specialised in pirated games or ANSI art, naturally filtering out older users, but other BBSes generally had a mix of ages – and hence opinions, forming perhaps some of the first public forums within which there was a wide diversity of opinion, something largely unheard-of to that point, and a glimpse of what was to come with the Internet (at least before the ‘filter bubbles’).

And so, in this realm that was largely unpoliced by external forces, teenagers acted out, engaging in all sorts of anti-establishment behaviour and creating the first digital counter-culture. But unlike other youth counter-cultures of the past, adults were not entirely shut out – ‘young adult only’ BBSes were often only so because they specialised in pirated games or ANSI art, naturally filtering out older users, but other BBSes generally had a mix of ages – and hence opinions, forming perhaps some of the first public forums within which there was a wide diversity of opinion, something largely unheard-of to that point, and a glimpse of what was to come with the Internet (at least before the ‘filter bubbles’).

In fact, the might of the Internet would be the only force capable of ending the reign of the BBS; as access costs came down its global nature proved to be too irresistable to modem users, and websites began to replace bulletin-boards as sources of information and interactivity. Eventually ‘broadband’ Internet connections would replace dial-up modems, terminating their users’ ability to connect to other personal computers over phone lines, this functionality not easily replaced as most Internet users had dynamic IP addresses, not fixed telephone numbers.

But while the Internet opened up the world for many, much would be lost in terms of the BBSes ability to foster local communities of individuals who could meet just as easily at the local pub as online. The limitation of local dialing provided a restriction that, far from being a hindrance to discussion and debate, actually encouraged people to have conversations about issues whose outcomes often had immediate impacts on their local communities, something the likes of Facebook and Twitter have failed to replace with the same depth and consequence.

Be the first to comment