“We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills.” – John F. Kennedy

It would not be unreasonable for NASA to assume that along with Kennedy’s 1961 commitment to reach the moon by the end of that decade came all of the resources required to make it happen. However, an American president is not a king, and despite his decree, in 1963 the US Congress slashed NASA’s budget by $600 million dollars.

Rumours were also flying fast and furious about potential, expensive setbacks NASA faced in its mission, including the mistaken notion that the Moon was covered in a 30-metre layer of dust and would be almost impossible to land on, and that astronauts would be killed in transit by radiation without thick lead shielding too heavy to get off the ground. NASA’s administration was in turmoil, and its head of manned space flight, responsible for the Apollo program, was fired.

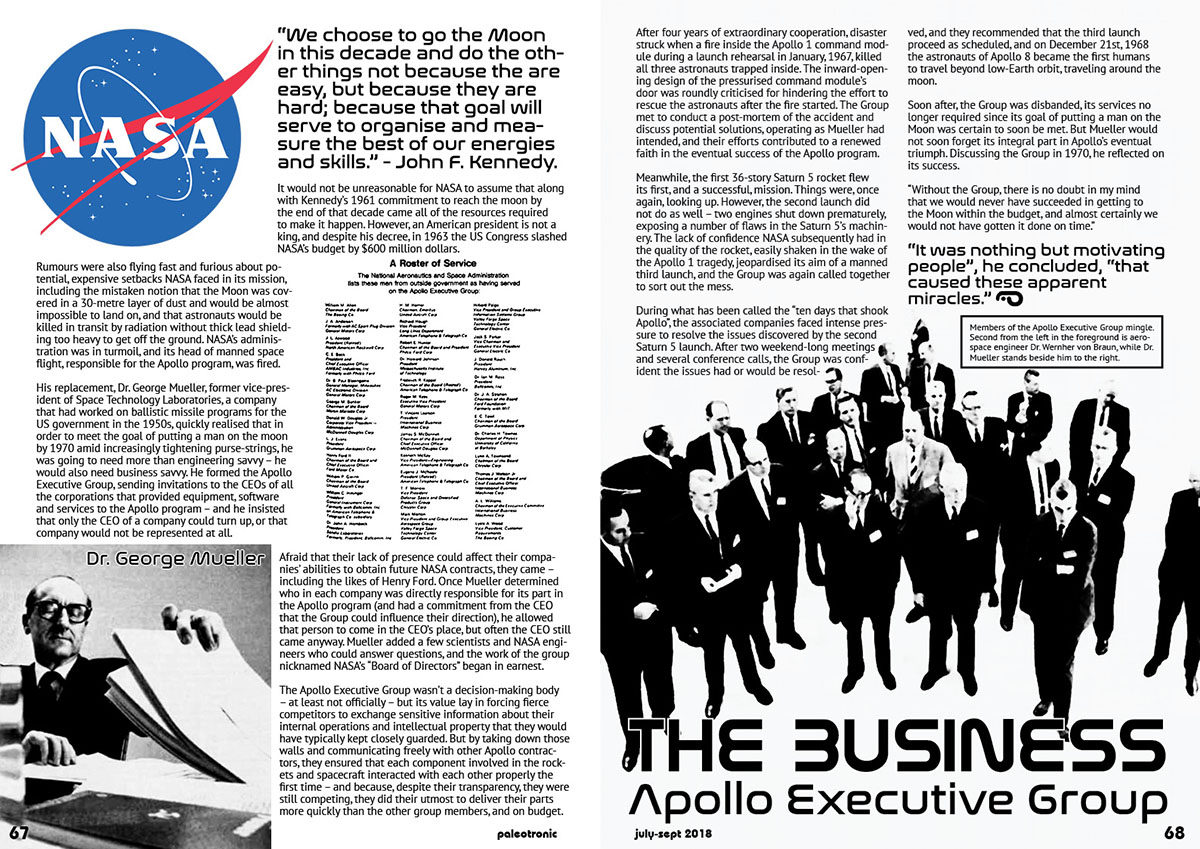

His replacement, Dr. George Mueller, former vice-president of Space Technology Laboratories, a company that had worked on ballistic missile programs for the US government in the 1950s, quickly realised that in order to meet the goal of putting a man on the moon by 1970 amid increasingly tightening purse-strings, he was going to need more than engineering savvy – he would also need business savvy. He formed the Apollo Executive Group, sending invitations to the CEOs of all the corporations that provided equipment, software and services to the Apollo program – and he insisted that only the CEO of a company could turn up, or that company would not be represented at all.

Afraid that their lack of presence could affect their companies’ abilities to obtain future NASA contracts, they came – including the likes of Henry Ford. Once Mueller determined who in each company was directly responsible for its part in the Apollo program (and had a commitment from the CEO that the Group could influence their direction), he allowed that person to come in the CEO’s place, but often the CEO still came anyway. Mueller added a few scientists and NASA engineers who could answer questions, and the work of the group nicknamed NASA’s “Board of Directors” began in earnest.

The Apollo Executive Group wasn’t a decision-making body – at least not officially – but its value lay in forcing fierce competitors to exchange sensitive information about their internal operations and intellectual property that they would have typically kept closely guarded. But by taking down those walls and communicating freely with other Apollo contractors, they ensured that each component involved in the rockets and spacecraft interacted with each other properly the first time – and because, despite their transparency, they were still competing, they did their utmost to deliver their parts more quickly than the other group members, and on budget.

After four years of extraordinary cooperation, disaster struck when a fire inside the Apollo 1 command module during a launch rehearsal in January, 1967, killed all three astronauts trapped inside. The inward-opening design of the pressurised command module’s door was roundly criticised for hindering the effort to rescue the astronauts after the fire started. The Group met to conduct a post-mortem of the accident and discuss potential solutions, operating as Mueller had intended, and their efforts contributed to a renewed faith in the eventual success of the Apollo program.

Meanwhile, the first 36-story Saturn 5 rocket flew its first, and a successful, mission. Things were, once again, looking up. However, the second launch did not do as well – two engines shut down prematurely, exposing a number of flaws in the Saturn 5’s machinery. The lack of confidence NASA subsequently had in the quality of the rocket, easily shaken in the wake of the Apollo 1 tragedy, jeopardised its aim of a manned third launch, and the Group was again called together to sort out the mess.

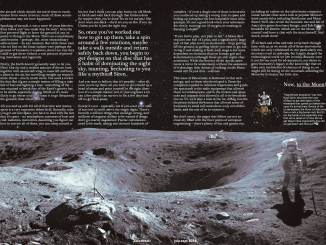

During what has been called the “ten days that shook Apollo”, the associated companies faced intense pressure to resolve the issues discovered by the second Saturn 5 launch. After two weekend-long meetings and several conference calls, the Group was confident the issues had or would be resolved, and they recommended that the third launch proceed as scheduled, and on December 21st, 1968 the astronauts of Apollo 8 became the first humans to travel beyond low-Earth orbit, traveling around the moon.

Soon after, the Group was disbanded, its services no longer required since its goal of putting a man on the Moon was certain to soon be met. But Mueller would not soon forget its integral part in Apollo’s eventual triumph. Discussing the Group in 1970, he reflected on its success.

“Without the Group, there is no doubt in my mind that we would never have succeeded in getting to the Moon within the budget, and almost certainly we would not have gotten it done on time.”

“It was nothing but motivating people”, he concluded, “that caused these apparent miracles.”

Be the first to comment