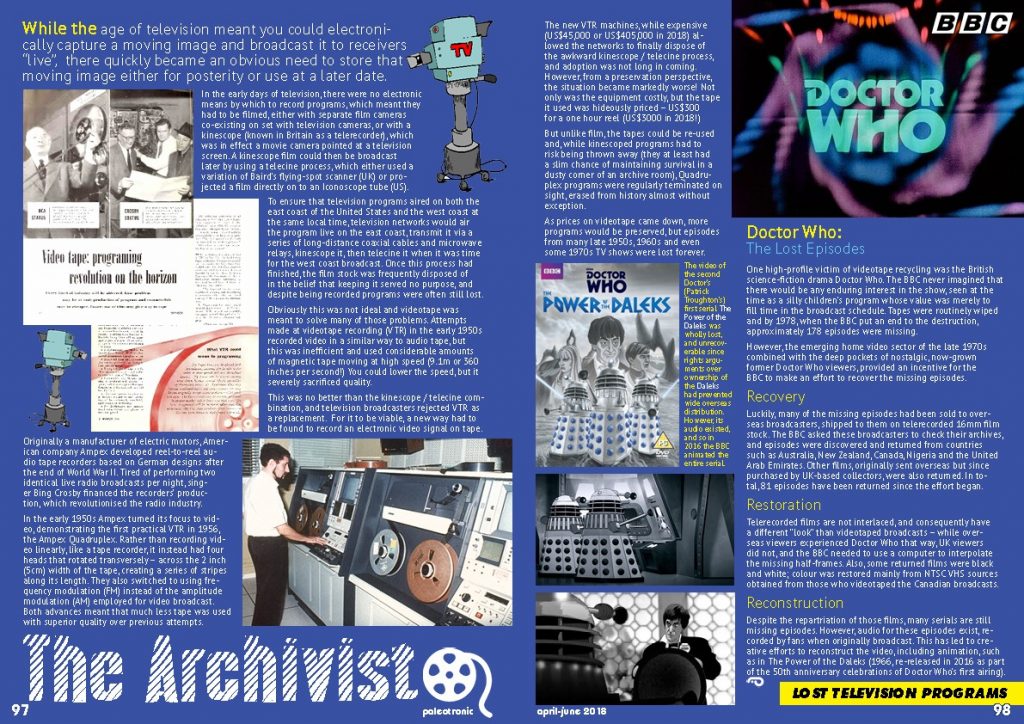

While the age of television meant you could electronically capture a moving image and broadcast it to receivers “live”, there quickly became an obvious need to store that moving image either for posterity or use at a later date.

In the early days of television, there were no electronic means by which to record programs, which meant they had to be filmed, either with separate film cameras co-existing on set with television cameras, or with a kinescope (known in Britain as a telerecorder), which was in effect a movie camera pointed at a television screen. A kinescope film could then be broadcast later by using a telecine process, which either used a variation of Baird’s flying-spot scanner (UK) or projected a film directly on to an Iconoscope tube (US).

To ensure that television programs aired on both the east coast of the United States and the west coast at the same local time, television networks would air the program live on the east coast, transmit it via a series of long-distance coaxial cables and microwave relays, kinescope it, then telecine it when it was time for the west coast broadcast. Once this process had finished, the film stock was frequently disposed of in the belief that keeping it served no purpose, and despite being recorded programs were often still lost.

Obviously this was not ideal and videotape was meant to solve many of those problems. Attempts made at videotape recording (VTR) in the early 1950s recorded video in a similar way to audio tape, but this was inefficient and used considerable amounts of magnetic tape moving at high speed (9.1m or 360 inches per second!) You could lower the speed, but it severely sacrificed quality.

Obviously this was not ideal and videotape was meant to solve many of those problems. Attempts made at videotape recording (VTR) in the early 1950s recorded video in a similar way to audio tape, but this was inefficient and used considerable amounts of magnetic tape moving at high speed (9.1m or 360 inches per second!) You could lower the speed, but it severely sacrificed quality.

This was no better than the kinescope / telecine combination, and television broadcasters rejected VTR as a replacement. For it to be viable, a new way had to be found to record an electronic video signal on tape.

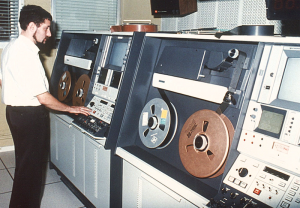

Originally a manufacturer of electric motors, American company Ampex developed reel-to-reel audio tape recorders based on German designs after the end of World War II. Tired of performing two identical live radio broadcasts per night, singer Bing Crosby financed the recorders’ production, which revolutionised the radio industry.

In the early 1950s Ampex turned its focus to video, demonstrating the first practical VTR in 1956, the Ampex Quadruplex. Rather than recording video linearly, like a tape recorder, it instead had four heads that rotated transversely – across the 2 inch (5cm) width of the tape, creating a series of stripes along its length. They also switched to using frequency modulation (FM) instead of the amplitude modulation (AM) employed for video broadcast. Both advances meant that much less tape was used with superior quality over previous attempts.

In the early 1950s Ampex turned its focus to video, demonstrating the first practical VTR in 1956, the Ampex Quadruplex. Rather than recording video linearly, like a tape recorder, it instead had four heads that rotated transversely – across the 2 inch (5cm) width of the tape, creating a series of stripes along its length. They also switched to using frequency modulation (FM) instead of the amplitude modulation (AM) employed for video broadcast. Both advances meant that much less tape was used with superior quality over previous attempts.

The new VTR machines, while expensive (US$45,000 or US$405,000 in 2018) allowed the networks to finally dispose of the awkward kinescope / telecine process, and adoption was not long in coming. However, from a preservation perspective, the situation became markedly worse! Not only was the equipment costly, but the tape it used was hideously priced – US$300 for a one hour reel (US$3000 in 2018!)

But unlike film, the tapes could be re-used and, while kinescoped programs had to risk being thrown away (they at least had a slim chance of maintaining survival in a dusty corner of an archive room), Quadruplex programs were regularly terminated on sight, erased from history almost without exception.

As prices on videotape came down, more programs would be preserved, but episodes from many late 1950s, 1960s and even some 1970s TV shows were lost forever.

One high-profile victim of videotape recycling was the British science-fiction drama Doctor Who. The BBC never imagined that there would be any enduring interest in the show, seen at the time as a silly children’s program whose value was merely to fill time in the broadcast schedule. Tapes were routinely wiped and by 1978, when the BBC put an end to the destruction, approximately 178 episodes were missing.

One high-profile victim of videotape recycling was the British science-fiction drama Doctor Who. The BBC never imagined that there would be any enduring interest in the show, seen at the time as a silly children’s program whose value was merely to fill time in the broadcast schedule. Tapes were routinely wiped and by 1978, when the BBC put an end to the destruction, approximately 178 episodes were missing.

However, the emerging home video sector of the late 1970s combined with the deep pockets of nostalgic, now-grown former Doctor Who viewers, provided an incentive for the BBC to make an effort to recover the missing episodes.

Recovery

Luckily, many of the missing episodes had been sold to overseas broadcasters, shipped to them on telerecorded 16mm film stock. The BBC asked these broadcasters to check their archives, and episodes were discovered and returned from countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Nigeria and the United Arab Emirates. Other films, originally sent overseas but since purchased by UK-based collectors, were also returned. In total, 81 episodes have been returned since the effort began.

Restoration

Telerecorded films are not interlaced, and consequently have a different “look” than videotaped broadcasts – while overseas viewers experienced Doctor Who that way, UK viewers did not, and the BBC needed to use a computer to interpolate the missing half-frames. Also, some returned films were black and white; colour was restored mainly from NTSC VHS sources obtained from those who videotaped the Canadian broadcasts.

Reconstruction

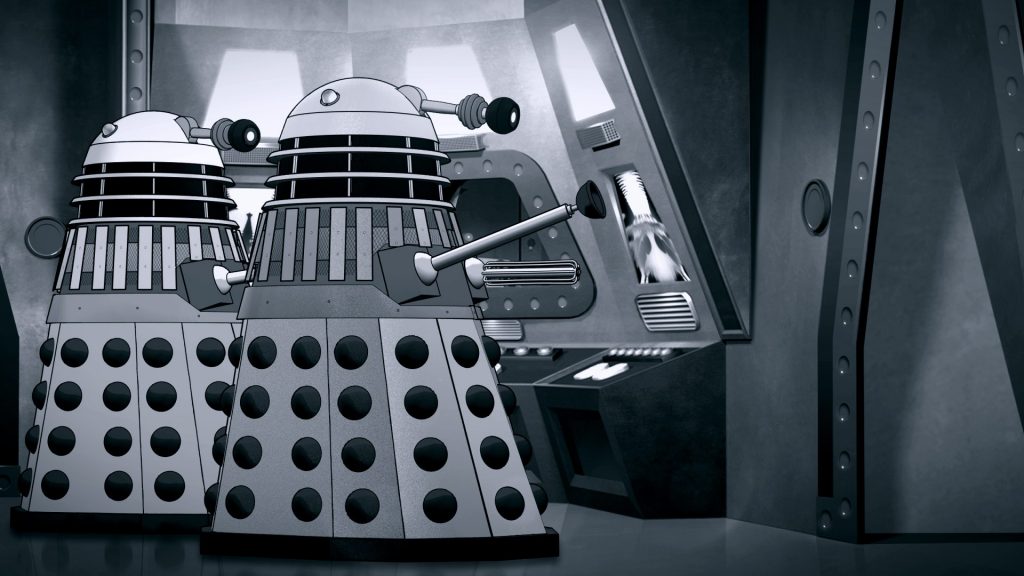

Despite the repatriation of those films, many serials are still missing episodes. However, audio for these episodes exist, recorded by fans when originally broadcast. This has led to creative efforts to reconstruct the video, including animation, such as in The Power of the Daleks (1966, re-released in 2016 as part of the 50th anniversary celebrations of Doctor Who’s first airing).

Be the first to comment