While the advertising model adopted by free-to-air television more than covered station-owners costs, media companies have always searched for solutions aimed at getting viewers to pay for programming directly.

Telemeter was one such solution. An early cablevision service, coaxial cables were run to households who wished to be connected to it. Reception of local free-to-air stations over the cable was provided for a monthly fee.

Telemeter was one such solution. An early cablevision service, coaxial cables were run to households who wished to be connected to it. Reception of local free-to-air stations over the cable was provided for a monthly fee.

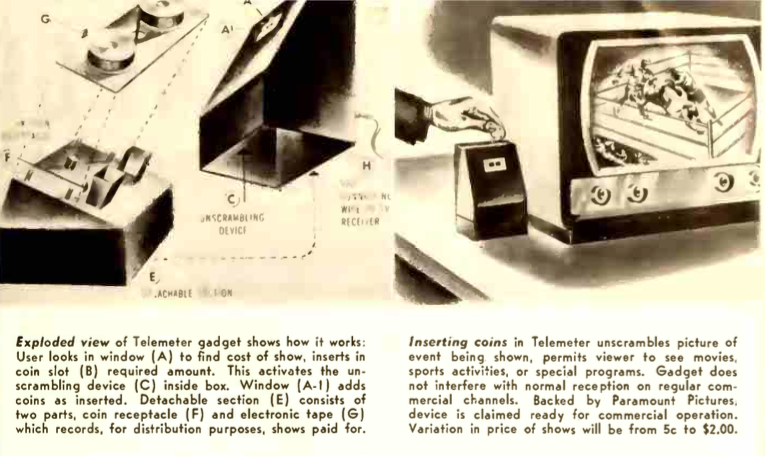

Three additional channels were also available, which were scrambled. Telemeter customers could get a descrambling box installed, but instead of paying a monthly fee, the box was coin operated.

Part-owned by movie studio Paramount, Telemeter was trialled in Palm Springs, California, in 1953. Customers could put US$1.25 into the box to watch first-run films and sporting events, such as boxing. However, local theatre owners became extremely unhappy at the prospect of competing with the service, and it was shut down after just six months.

Part-owned by movie studio Paramount, Telemeter was trialled in Palm Springs, California, in 1953. Customers could put US$1.25 into the box to watch first-run films and sporting events, such as boxing. However, local theatre owners became extremely unhappy at the prospect of competing with the service, and it was shut down after just six months.

Nearly five years later, in 1959, Telemeter started up again, this time in Ontario, Canada, outside the reach of the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) which at the time was staunchly against pay-television services.

It launched with one thousand subscribers, once again showing first-run movies and commercial-free TV shows.

In 1961, Telemeter signed deals with two Toronto sports teams to broadcast their games; Broadway shows and opera productions also made appearances on the system.

However, although at its peak it had 5800 subscribers, Telemeter was deemed commercially unviable and was never expanded to other cities. It was shut down in early 1965.

While Telemeter wasn’t a success, it was the first system to introduce pay-per-view services into cable-based television broadcast systems. It wouldn’t be until 1972, with the launch of HBO, that premium television services would return to channel dials and remain.

Scrambled signals teased basic cablevision customers – visible in the channel lineup of their cable boxes (and often with unscrambled audio) they were virtually unwatchable.

Premium cable channels like HBO, Showtime and Cinemax in the United States; and SuperChannel in Canada aired second-run movies, comedy specials and sporting events starting in the 1970s. Cablevision companies would rent a second “cable box” to customers that descrambled the channels for an additional monthly fee, which could easily double or triple a customers cablevision bill.

Premium cable channels like HBO, Showtime and Cinemax in the United States; and SuperChannel in Canada aired second-run movies, comedy specials and sporting events starting in the 1970s. Cablevision companies would rent a second “cable box” to customers that descrambled the channels for an additional monthly fee, which could easily double or triple a customers cablevision bill.

Not surprisingly, most people opted out of the service, unable to stomach the extra cost, but the channels’ lineups were prominently listed on computer-generated TV schedule channels, and grated on viewers only able to watch commercial-filled programming.

A dubious justification soon emerged: since the scrambled signal came in to your house arbitrarily (or through the air, in the case of satellite TV), you were well within your rights to do whatever you wanted with it, including descramble it. Generally law-abiding people began to build descramblers.

But how did they do that? Well, to explain descrambling, first we need to explore how the signal is scrambled, or encrypted.

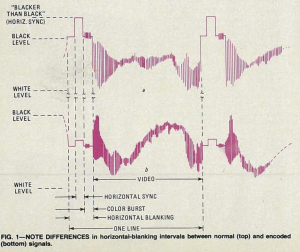

Most early television encryption systems worked by modifying the electromagnetic signals that make up the audio and video portions of a television channel. To review, a video signal has both horizontal and vertical synchronisation pulses which tell a television set when to advance the electron gun to the next line, or frame of video.

Most early television encryption systems worked by modifying the electromagnetic signals that make up the audio and video portions of a television channel. To review, a video signal has both horizontal and vertical synchronisation pulses which tell a television set when to advance the electron gun to the next line, or frame of video.

The earliest systems modified these pulses so that they couldn’t be recognised by the television directly – either by suppressing them or relocating them to a different frequency – and instead of displaying a coherent picture, the TV would instead serve up a jumbled mess. By disrupting the sync pulses, other crucial information such as the colourburst signal was also lost, making a true dog’s breakfast of the image.

A pay-TV decoder box converted the modified signal back into the original by reversing what the encoder had done, restoring the sync pulses and making the rest of the signal legible to the television’s video circuitry once more. On systems where the blanking pulses were hidden, it was a simple matter of knowing where to look. But what if they were removed entirely?

Well, there was someplace else the synchronisation signals could be found – in the audio signal. But to understand how that could be, we need to take a brief detour somewhere else.

Stereo FM radio works by broadcasting a primary frequency-modulated monophonic signal (made up of the combined left and right channels of a stereo audio program) so that monophonic FM radio receivers can still reproduce it as if it were a non-stereo FM signal.

Stereo FM radio works by broadcasting a primary frequency-modulated monophonic signal (made up of the combined left and right channels of a stereo audio program) so that monophonic FM radio receivers can still reproduce it as if it were a non-stereo FM signal.

Embedded in that signal is a “pilot tone” at 19Khz which tells a stereo FM receiver that there is additional information on a frequency at double that number (38Khz) which contains a signal made up of the left channel minus the right channel and allows for decoding of both frequencies back into a stereo signal.

Multichannel Television Sound (or MTS) uses a similar system to add additional audio channels to a television signal – and most pay-TV channels had stereo sound. However, it encodes that information at 31.5Khz instead of 38, and has a pilot tone at 15.75Khz.

Happily, the horizontal sync rate in an NTSC television signal is 15.75Mhz – 1,000 times the MTS pilot tone! So by using circuitry common to FM radio receivers, we can extract the pilot tone and use it to recreate the horizontal sync pulse needed for a stable picture.

This is what the pay-TV box from the cable company did. It was a form of “security by obscurity”, where the only thing preventing people from violating it was the knowledge of how it functioned. It only worked as long as the secret stayed secret, and despite non-disclosure agreements keeping people employed in the pay-TV industry quiet, it wasn’t long before technically-minded people reverse engineered the boxes to divine their mysteries.

Once they had, a booming market in pirate pay-TV decoders sprang up, with the devices available by mail order through addresses listed in the classified section of amateur radio publications or local newspapers. Some even sent plans for them into electronics magazines, as demonstrated here.

Another way to avoid paying for channels like HBO in the early 1980s was to buy a satellite system, but pay TV operators didn’t tolerate it for long…

Another way to avoid paying for channels like HBO in the early 1980s was to buy a satellite system, but pay TV operators didn’t tolerate it for long…

In the 1970s, as cable TV proliferated and specialty cable-only channels began to appear, satellite television engineers started to build their own personal receiving stations so that they could acquire (and watch) these channels the same way their local cable company did, from communication satellites orbiting the Earth.

There was no subscription required – these channels were broadcast “in the clear” and anyone with a satellite dish and the required equipment could receive and watch them. Some enterprising individuals began to sell satellite systems commercially to homes and businesses.

One such individual was a man named John MacDougall. John had left college after two years of studying engineering, and made a living installing satellite systems in Ocala, Florida. In 1983, he opened his own satellite dealership, which did well for the first few years, but then on January 15th, 1986 HBO, which had turned a blind eye to home satellite users up to that point, started to scramble their satellite signal.

One such individual was a man named John MacDougall. John had left college after two years of studying engineering, and made a living installing satellite systems in Ocala, Florida. In 1983, he opened his own satellite dealership, which did well for the first few years, but then on January 15th, 1986 HBO, which had turned a blind eye to home satellite users up to that point, started to scramble their satellite signal.

While HBO offered to sell descrambling equipment to home satellite users, they weren’t interested in paying for it (if they had, they wouldn’t have installed a satellite system!) John’s business was decimated overnight, as sales evaporated. He tried to cut his expenses, but ended up taking a part-time job with a satellite uplink company (which “uplinked” video to satellites for distribution to receiving stations).

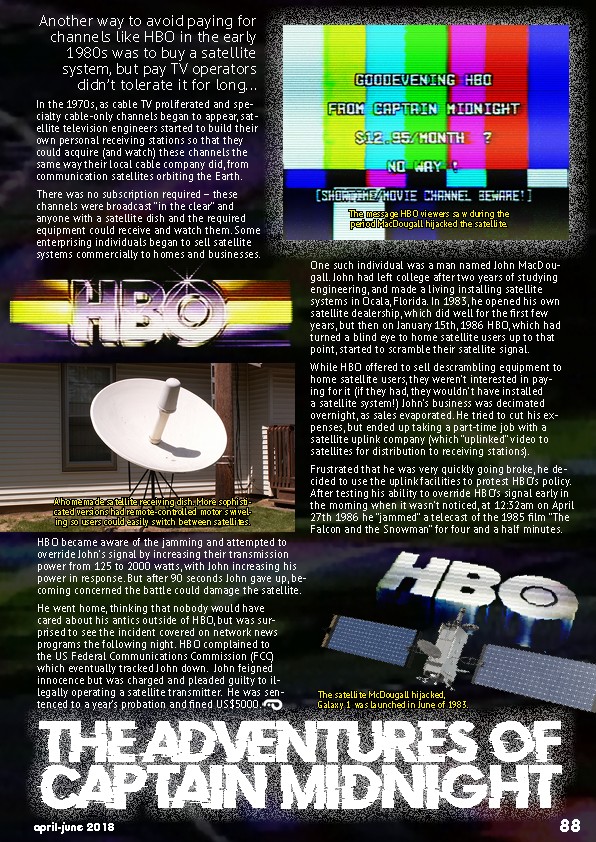

Frustrated that he was very quickly going broke, he decided to use the uplink facilities to protest HBO’s policy. After testing his ability to override HBO’s signal early in the morning when it wasn’t noticed, at 12:32am on April 27th 1986 he “jammed” a telecast of the 1985 film “The Falcon and the Snowman” for four and a half minutes.

HBO became aware of the jamming and attempted to override John’s signal by increasing their transmission power from 125 to 2000 watts, with John increasing his power in response. But after 90 seconds John gave up, becoming concerned the battle could damage the satellite.

He went home, thinking that nobody would have cared about his antics outside of HBO, but was surprised to see the incident covered on network news programs the following night. HBO complained to the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) which eventually tracked John down. John feigned innocence but was charged and pleaded guilty to illegally operating a satellite transmitter. He was sentenced to a year’s probation and fined US$5000.

Be the first to comment