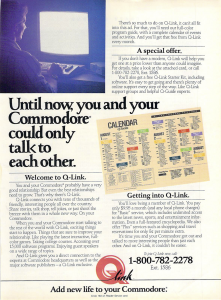

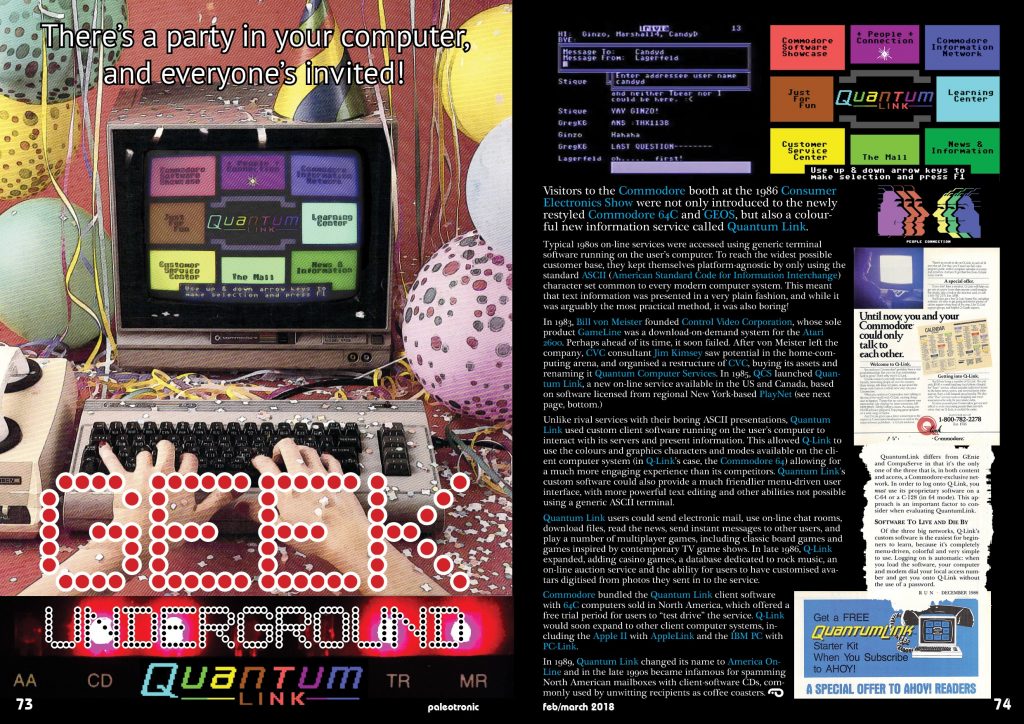

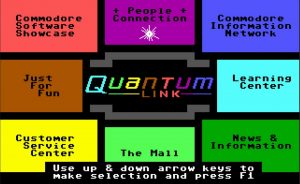

Visitors to the Commodore booth at the 1986 Consumer Electronics Show were not only introduced to the newly restyled Commodore 64C and GEOS, but also a colourful new information service called Quantum Link.

Typical 1980s on-line services were accessed using generic terminal software running on the user’s computer. To reach the widest possible customer base, they kept themselves platform-agnostic by only using the standard ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) character set common to every modern computer system. This meant that text information was presented in a very plain fashion, and while it was arguably the most practical method, it was also boring!

In 1983, Bill von Meister founded Control Video Corporation, whose sole product GameLine was a download-on-demand system for the Atari 2600. Perhaps ahead of its time, it soon failed. After von Meister left the company, CVC consultant Jim Kimsey saw potential in the home-computing arena, and organised a restructure of CVC, buying its assets and renaming it Quantum Computer Services.

In 1983, Bill von Meister founded Control Video Corporation, whose sole product GameLine was a download-on-demand system for the Atari 2600. Perhaps ahead of its time, it soon failed. After von Meister left the company, CVC consultant Jim Kimsey saw potential in the home-computing arena, and organised a restructure of CVC, buying its assets and renaming it Quantum Computer Services.

In 1985, QCS launched Quantum Link, a new on-line service available in the US and Canada, based on software licensed from regional New York-based PlayNet.

Unlike rival services with their boring ASCII presentations, Quantum Link used custom client software running on the user’s computer to interact with its servers and present information. This allowed Q-Link to use the colours and graphics characters and modes available on the client computer system (in Q-Link’s case, the Commodore 64) allowing for a much more engaging experience than its competitors. Quantum Link’s custom software could also provide a much friendlier menu-driven user interface, with more powerful text editing and other abilities not possible using a generic ASCII terminal.

Quantum Link users could send electronic mail, use on-line chat rooms, download files, read the news, send instant messages to other users, and play a number of multiplayer games, including classic board games and games inspired by contemporary TV game shows. In late 1986, Q-Link expanded, adding casino games, a database dedicated to rock music, an on-line auction service and the ability for users to have customised avatars digitised from photos they sent in to the service.

Commodore bundled the Quantum Link client software with 64C computers sold in North America, which offered a free trial period for users to “test drive” the service. Q-Link would soon expand to other client computer systems, including the Apple II with AppleLink and the IBM PC with PC-Link.

Commodore bundled the Quantum Link client software with 64C computers sold in North America, which offered a free trial period for users to “test drive” the service. Q-Link would soon expand to other client computer systems, including the Apple II with AppleLink and the IBM PC with PC-Link.

In 1989, Quantum Link changed its name to America On-Line and in the late 1990s became infamous for spamming North American mailboxes with client-software CDs, commonly used by unwitting recipients as coffee coasters.

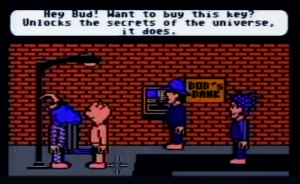

Club Caribe

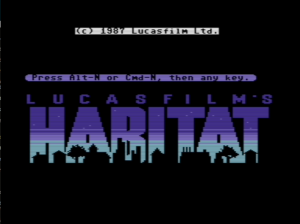

Initially called Habitat during its beta-test period and renamed Club Caribe at its launch, this popular feature of Quantum Link was developed by Lucasfilm Games. Users were able to design a personalised avatar and then wander around a virtual island resort, interacting with other users, collecting and using objects and money.

Club Caribe was known for its quirks – for example, users could treat their avatars’ heads as objects, taking them off and carrying them around. Those who made the mistake of dropping their heads were mortified upon the realisation that other users could steal them, leading to the unsettling display of headless avatars wandering around the island.

Club Caribe was known for its quirks – for example, users could treat their avatars’ heads as objects, taking them off and carrying them around. Those who made the mistake of dropping their heads were mortified upon the realisation that other users could steal them, leading to the unsettling display of headless avatars wandering around the island.

The Habitat software would become the basis for Lucasfilm Games’ SCUMM engine, used in (and in-part named for) the first point-and-click adventure game, Maniac Mansion, in which a teenager goes on a quest to rescue his girlfriend from a mad scientist. The game was lauded for its comedic cut-scenes and wacky humour.

The Habitat software would become the basis for Lucasfilm Games’ SCUMM engine, used in (and in-part named for) the first point-and-click adventure game, Maniac Mansion, in which a teenager goes on a quest to rescue his girlfriend from a mad scientist. The game was lauded for its comedic cut-scenes and wacky humour.

However, despite Club Caribe’s popularity, technology marched on, and as common usage of the Commodore 64 declined, so did the userbase (and the profitability) of the Quantum Link service. It was no surprise to anyone when, in 1994, America On-Line finally decided to close Q-Link’s virtual doors, shutting it down in November that year, and bringing the 8-bit era of telecomputing to a quiet, but emphatic close.

Over the next several years America On-Line would find itself confronted by its own increasing irrelevance. As the Internet gradually took over from on-line services, AOL would eventually transition to a web-portal and then a successful media company.

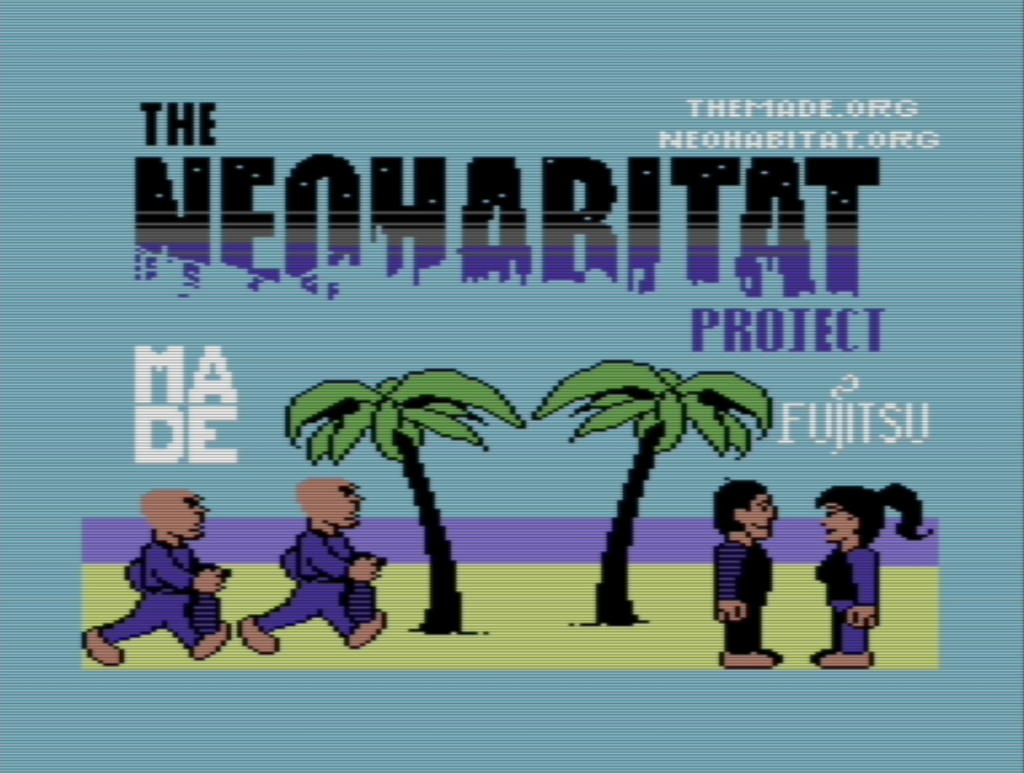

The NeoHabitat Project

The Neohabitat project is an effort to revive the Quantum Link Club Caribe service. Modern users can experience Neohabitat by visiting the project’s website at www.neohabitat.org and downloading a customised Commodore 64 emulator.

Paleotronic spoke with one of the project’s lead developers, Steve Salevan, about why he decided to help resurrect Habitat…

Were you a Quantum Link user back in the day?

My dad was a QuantumLink user and the service was my first exposure to the Internet as a young kid. I remember being absolutely entranced that we could obtain games and SID tunes on demand, and I’d constantly pepper my dad with download requests.

Alas, I first discovered Habitat/Club Caribe through reading an old Q-Link magazine as a teenager, long after the service had been shut down.

What part do you play in the NeoHabitat project?

I’m a lead developer and provide hosting for Neohabitat’s online presence through Spine, the cloud provider that I created.

What prompted you to help resurrect Habitat?

I’d always wanted to play Habitat since first discovering it and I learned of the Neohabitat project through a post on Reddit’s Commodore forum, one fateful Saturday afternoon. I’d just quit my full-time job at Twitter and was looking for a fun hack to get into before transitioning into my current role at Spine. Gosh, was it ever.

What main challenges were there in resurrecting Habitat?

Initially, our biggest challenge was in building a server that could speak the 1980s protocol used by the Commodore 64 client software. Randy (Farmer) tackled this problem by implementing a Node.js-based bridging service to translated this protocol into modern JSON, allowing us to focus next on building the game logic.

We had a major leg up on the game logic side of the equation, as Randy and Chip (Morningstar) had recently open sourced Elko, a foundation for MMO services that was a direct descendant of the technology they’d built for Habitat. Randy developed much of the base logic we’d need to port the original PL/1 source to this Elko-based platform. Habitat was an extremely expansive game for its time, with over a hundred different interactive objects, all with involved logic that needed to be correctly ported and tested across multiple client conditions.

This task was a major undertaking, but it could be parallelized across multiple developers, and by this point we’d attracted a growing developer community who were eager to get involved.

This led to our next big challenge: rigging up a development environment in those days was an involved process, requiring developers to bring up three separate services and two databases. We solved this problem by containerizing everything and providing Docker Compose automation to reduce the onboarding process to a single command. By doing so, we rapidly improved the project’s iteration speed, attracting the contributions we needed and allowing us to launch our pre-alpha on top of Spine.

This led to our next big challenge: rigging up a development environment in those days was an involved process, requiring developers to bring up three separate services and two databases. We solved this problem by containerizing everything and providing Docker Compose automation to reduce the onboarding process to a single command. By doing so, we rapidly improved the project’s iteration speed, attracting the contributions we needed and allowing us to launch our pre-alpha on top of Spine.

Once we’d implemented the bulk of the game logic, our next challenge became one of populating the world with its original launch content. We possessed the original source files for this content, but we needed to translate them into JSON (data) compatible with the Mongo database sitting behind our game logic server. We developed a tool called Regionator to do so, which our Geography team used to map out and piece together the vast majority of the 1987 launch world, over 2000 rooms in total.

By this point, much of Neohabitat was working, but the login process was still quite cumbersome, requiring users to navigate through numerous obscure corners of the original QuantumLink software. While this provided an authentic 1980s login experience, we felt that it would dissuade new users from joining in on the fun.

By this point, much of Neohabitat was working, but the login process was still quite cumbersome, requiring users to navigate through numerous obscure corners of the original QuantumLink software. While this provided an authentic 1980s login experience, we felt that it would dissuade new users from joining in on the fun.

Enter Gary Lake-Schaal, a legendary Commodore hacker who managed to recompile the original Habitat client from scratch and wrote us a custom launcher to boot, complete with a custom splash screen and awesome PETSCII art. Gary’s new client cut the login process down to 30 seconds and allowed us to build single-click client launchers for both Windows and OS X.

What’s the future look like for NeoHabitat?

The Neohabitat community continues to grow, attracting over 100 unique users every month. We’re planning some regular in-world events to promote the service, and we’ve created a Node-based bot framework to enable the development of interactive in-world characters. The MADE is also building a permanent exhibit within their museum, bringing Habitat to a whole new generation of players, and you’ll likely see it at this year’s GDC (Game Developers Conference)!

Thanks Steve!

Halt and Catch Fire

Halt and Catch Fire’s fictional 1980s startup Mutiny is based on PlayNet, a New York-based on-line service founded in 1983 by two former GE Global Research employees, Dave Panzl and Howard Goldberg. PlayNet used custom software running on customers’ Commodore 64s that provided games that they could play against each other while chatting, such as Checkers and Connect 4.

The founders initially bootstrapped the company with their own money, but once it gained traction obtained $2.5 million in outside venture capital. At its peak, PlayNet employed 30 people and had 3000 customers, with around 200 able to be logged in at one time, using 300 baud modems.

In 1985, Quantum Computer Services licensed the PlayNet software and used it as the basis for Quantum Link, paying a royalty to PlayNet. Unfortunately, it appears there wasn’t enough room in the market for two Commodore 64-only on-line services, and PlayNet declared bankruptcy in 1986. Probably sensing PlayNet didn’t have the funds necessary for a protracted legal battle, Quantum Link ceased paying royalties afterward, forcing PlayNet to shut down in 1988.

Halt and Catch Fire was a television series on AMC (American Movie Channel) that ran from 2014 to 2017. The show follows a number of characters involved in the technology industry from the early 1980s until the mid-1990s. In season two, programmer Cameron Howe (Mackenzie Davis, right) forms Mutiny with Donna Clark (Kerry Bishé, left), a former Texas Instruments engineer.

Although it had low viewership throughout its run, it was critically acclaimed, and that led AMC to renew it three times, the last time for a final season, which had a satisfying finale. If you haven’t yet, Paleotronic wholeheartedly recommends watching this show!

Be the first to comment