Marty’s camera in Back to the Future is one cool piece of gear, but his JVC GR-C1 VideoMovie was actually over four years old at this point – an early version of it had been demonstrated at the Consumer Electronics Show in 1981.

A video camera with an in-built recorder was revolutionary for the early 1980s. Up until then, you needed an external recorder for your so-called portable video camera. Many of these recorders didn’t have batteries, which severely limited your mobility. And the ones that did were heavy! Many videographers found themselves slinging the video recorders and batteries over their shoulder, bouncing against their hips as they ran down the street trying to get the perfect shot of parades or protests, leading to all sorts of workplace injuries. Not cool! There had to be a better way, and video camera manufacturers, including JVC, set out to find it.

Firstly, JVC realised that using full-sized VHS tapes in an “integrated” camera and recorder was going to bulk up their new “camcorder” significantly. Engineers found a solution – use smaller tapes! However, there were concerns over compatibility. In order to transfer their video to their home VCR, would consumers have to play it back over a composite cable? That would be a very poor user experience. What to do?

JVC designed their new smaller “compact VHS” (or VHS-C) tape so that it would fit into a larger VHS tape “shell”. This “rebigginator” tape could then be placed into a standard VCR and played back, allowing for quick editing. Improvements in battery technology, and the ongoing miniaturisation of electronic components combined with VHS-C to allow JVC to release the VideoMovie to the public in 1984, and the era of the home movie had begun – so had the era of crowd-sourced news video, and professional news videographers found themselves adding a camcorder or two to their kit, for when they really needed mobility free of wires and cumbersome equipment. Gone were the days of hip and back injuries!

VHS-C would get an upgrade in the late 1980s. S-VHS-C (or Compact Super VHS) which had 60% increased video bandwidth, providing a horizontal resolution higher than NTSC broadcast television. However, by that time Sony’s Betacam format had become the industry standard, and S-VHS-C did not see any real uptake by professional videographers.

Speaking of the Sony Betacam…

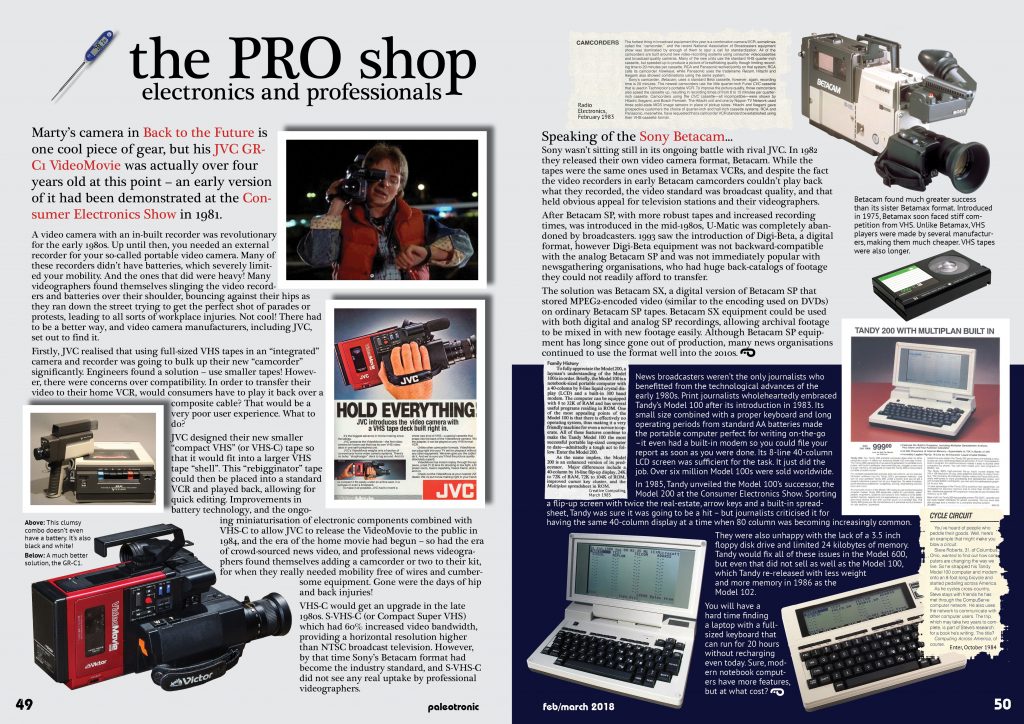

Sony wasn’t sitting still in its ongoing battle with rival JVC. In 1982 they released their own video camera format, Betacam. While the tapes were the same ones used in Betamax VCRs, and despite the fact the video recorders in early Betacam camcorders couldn’t play back what they recorded, the video standard was broadcast quality, and that held obvious appeal for television stations and their videographers. After Betacam SP, with more robust tapes and increased recording times, was introduced in the mid-1980s, U-Matic was completely abandoned by broadcasters. 1993 saw the introduction of Digi-Beta, a digital format, however Digi-Beta equipment was not backward-compatible with the analog Betacam SP and was not immediately popular with newsgathering organisations, who had huge back-catalogs of footage they could not readily afford to transfer.

The solution was Betacam SX, a digital version of Betacam SP that stored MPEG2-encoded video (similar to the encoding used on DVDs) on ordinary Betacam SP tapes. Betacam SX equipment could be used with both digital and analog SP recordings, allowing archival footage to be mixed in with new footage easily. Although Betacam SP equipment has long since gone out of production, many news organisations continued to use the format well into the 2010s.

News broadcasters weren’t the only journalists who benefitted from the technological advances of the early 1980s.

Print journalists wholeheartedly embraced Tandy’s Model 100 after its introduction in 1983. Its small size combined with a proper keyboard and long operating periods from standard AA batteries made the portable computer perfect for writing on-the-go –it even had a built-in modem so you could file your report as soon as you were done. Its 8-line 40-column LCD screen was sufficient for the task. It just did the job. Over six million Model 100s were sold worldwide.

In 1985, Tandy unveiled the Model 100’s successor, the Model 200 at the Consumer Electronics Show. Sporting a flip-up screen with twice the real-estate, arrow keys and a built-in spreadsheet, Tandy was sure it was going to be a hit – but journalists criticised it for having the same 40-column display at a time when 80 column was becoming increasingly common. They were also unhappy with the lack of a 3.5 inch floppy disk drive and limited 24 kilobytes of memory.

Tandy would fix all of these issues in the Model 600, but even that did not sell as well as the Model 100, which Tandy re-released with less weight and more memory in 1986 as the Model 102.

You will have a hard time finding a laptop with a full-sized keyboard that can run for 20 hours without recharging even today. Sure, modern notebook computers have more features, but at what cost?

Be the first to comment