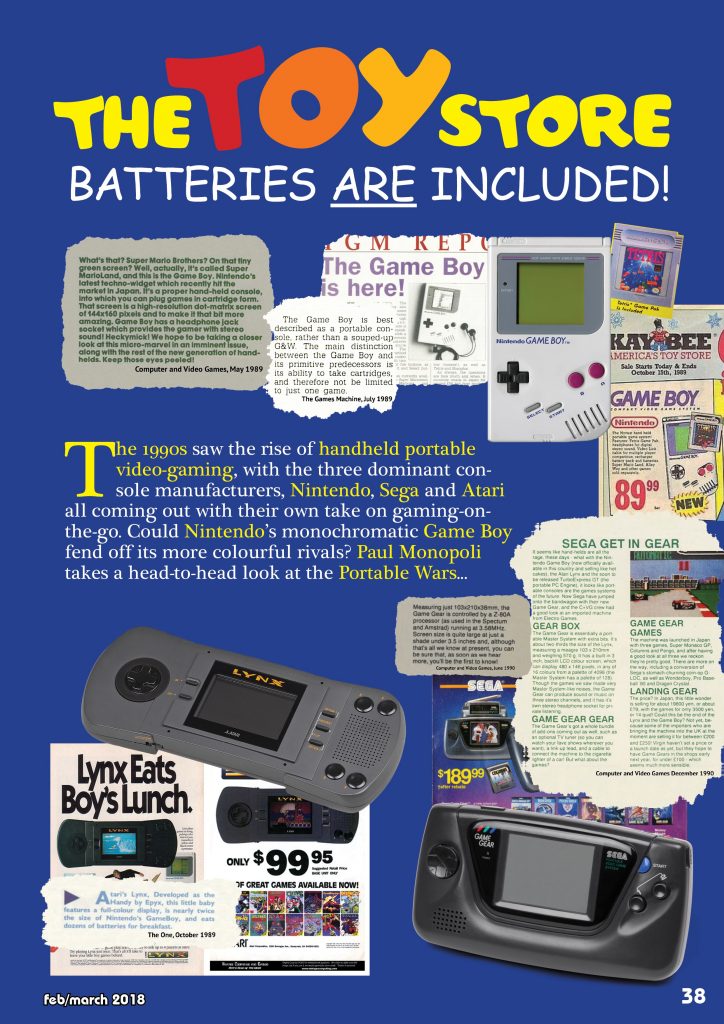

The 1990s saw the rise of handheld portable video-gaming, with the three dominant console manufacturers, Nintendo, Sega and Atari all coming out with their own take on gaming-on-the-go. Could Nintendo’s monochromatic Game Boy fend off its more colourful rivals? Paul Monopoli takes a head-to-head look at the Portable Wars…

Video games were introduced to the mainstream market in the 1970s, but really hit their stride in the following decade. Where parents might have had problems getting their children to stop watching TV and go to bed, they now had the same problem with video games. The Nintendo Entertainment System and the Sega Master System were the leaders in this, still rather newish form of entertainment, with Atari losing marketshare as the 80s rolled on.

Nintendo was coming up to the end of a very successful decade. Their Nintendo Entertainment System had gone from strength to strength, and their portable gaming line, the Game and Watch series, kept gamers going while they were away from home. There was a problem with the Game and Watch line though, and it is in part the fault of the Nintendo Entertainment System itself.

Nintendo had sought to create a home entertainment system that could captivate gamers for hours on end. Game and Watch titles contained a single screen, with progress involving the game becoming more difficult to the point where it was impossible to play anymore. NES games like Contra and Ninja Gaiden introduced the concept of “just one more go”, pushing gamers to progress through a multi level story as they improved. With this evolution of gaming something had to change, and Nintendo wanted to keep its handheld market alive. Under the watchful eye of Game and Watch designer, Gunpei Yokoi, the Game Boy was born.

With its poor LCD screen, the Game Boy did not have a strong following at Nintendo HQ, with many employees dismissing it as a potential failure. However, the success of the Game Boy can be attributed to some very clever marketing and design. Containing a control layout similar to the established NES controller, the Game Boy entered the market with a plethora of gamers who could easily pick up and play the system with little need to learn how to use it. Sequels to successful NES titles also played a big part in the system’s early success, but the biggest initial selling point was a its bundled game.

Tetris, designed by Alexei Pajitnov, was bundled with the Game Boy in the US, Europe and Australia. Nintendo quickly realised it had a ‘killer app’ with this addictive title, and used it to market their new handheld. Nintendo ensured that Tetris contained the ability to use the link cable, one of the features used to market the system. The biggest surprise for Nintendo was that not only gamers became addicted to the Russian puzzle game. Housewives were picking up their children’s Game Boys when they weren’t in use and dropping pieces into the well, creating lines and often beating their children’s high scores.

While the Game Boy was an immediate hit with the public, at this stage it didn’t have a rival. It stood alone in a new gaming market that Nintendo had created. With all of its success, the Game Boy was not without fault. While the public adored the little handheld, many critics noted that the screen was poor, as was the battery life of the console. However, over the coming years these weaknesses would become the Game Boy’s strengths as rivals to the handheld crown entered the market.

In 1986 development of the Atari Lynx began at Epyx software. At the time Epyx was best known for its 8-bit sports titles, Summer Games, Winter Games, and California Games. Known as the “Epyx Handy”, this handheld was developed without knowledge of what was happening at Nintendo’s Kyoto HQ. Like the Game Boy, games were stored on cartridges, but unlike the Game Boy the screen was in full colour. With the decline of the 8-bit market and the resources needed to design the console, Epyx had developed some financial problems. At the 1989 CES it tried to market the console to established manufacturers. If it could partner with one of the big shakers in the gaming industry then it might have a chance of releasing the Handy, while earning enough money to stay in the black.

Nintendo declined to partner with Epyx as the Game Boy was only a few months away from release. Sega also turned it down, leaving Epyx in a bind. Thankfully it found a saviour in the form of Atari, who, after two failed hardware releases, was still living off the scraps of its decade old 2600 console. Similar to the deal Nintendo pitched to Atari six years earlier, Epyx would manufacture the hardware and software while Atari would market and distribute the console. Sadly, the deal did not save Epyx, which declared bankruptcy before the year had ended. Atari now found itself as sole owner of the Handy.

Atari made some modifications to the device and showcased it at the following CES. Its new title, the Atari ‘Portable Colour Entertainment System’ was an obvious dig at the Nintendo Entertainment System, and the marketing line for the Game Boy, the ‘Compact Video Game System’. The name may have concerned the Atari legal team, or it was simply a placeholder name, as when the console launched it was known as the Lynx.

While the Lynx was critically acclaimed for its processing ability and colour screen, the size of the console and poor battery life was noted in the gaming press at that time. Its Japanese rival boasted a huge library of games, while most of the successful Atari titles were games that the public had grown out of. There was no Tetris or Super Mario on the Lynx, and games like Chip’s Challenge and California Games were poor substitutes. The reputation of Atari was also a factor, as many considered them a one hit wonder thanks to their 2600, with the 5200 and 7200 failing to make an impact with gamers. While Atari claimed that sales of the Lynx met with their expectations, it was obvious that Nintendo was the winner of this round. With two new rivals on the horizon it was clear that Atari’s situation was about to get a lot worse.

The success of the Game Boy inspired Nintendo’s rivals to develop their own handheld systems, and possibly take away a chunk of the handheld market from the Big N. Sega released its Game Gear in October of 1990, and at the 1991 CES the console had a decent amount of floor space devoted to it. While Sega was just releasing its first handheld console, Atari was debuting its Lynx 2, a smaller version of the original hardware, and Nintendo was improving on its already successful formula. The Nintendo Four Player Adapter allowed gamers to connect four Game Boy consoles, with new games like F1-Race and Faceball 2000 taking advantage of the new device.

The hardware in the Game Gear is similar to the Sega Master System, allowing many titles from that console to be ported on to the Game Gear. That, along with ports of Sega’s successful arcade hits, saw it steal some of the market from Nintendo, but even more from Atari, who needed it now more than ever. Sega used the similarities between the Game Gear and Master System to develop an adapter, allowing gamers to play Master Systems titles on their new portable console. Sega also took a leaf out of Nintendo’s book by marketing the console with the addictive puzzle game, Columns.

Pricing for the Game Gear was set between the Game Boy and Lynx, and advertising directly targeted Nintendo. It was apparent that Sega did not consider Atari to be a major form of competition, and it avoided any public squabbles with them. Nintendo considered some of the advertising to be offensive to its audience, though sales were not affected.

Commentators at the time noted that while Sega had the backing of a superior range of games, that the Lynx boasted a slightly larger screen and better battery life. However, these things weren’t important to gamers, who wanted to play titles such as Wonderboy 3 and Golden Axe on the go. Sega was in a better financial decision than Atari, and was able to market its console into a comfortable second place behind Nintendo. The gaming press now noted that part of the success of the Game Boy was one of its biggest failings. While in 1989 the battery life was seen as poor its rivals had proven that colour was a liability, and that the blurry, green LCD screen actually helped the Game Boy retain its battery life.

As the early 90s were ending the handheld market was looking like a two horse race, with Nintendo taking a comfortable lead, sales of the Game Gear improving and the Lynx and Turbo Express trailing behind. Sega was starting to branch out into modifications for their Megadrive console, stretching its resources toward the Game Gear thin. However, Nintendo was just getting started and the mid 90s saw the death of the Lynx. Though Atari had improved the physical appearance of the Lynx with the release of the Lynx 2, it wasn’t enough to save the console. Atari ceased production on the Lynx and pooled its resources into the failing Jaguar.

Sega decided to up the stakes and released a handheld version of the Megadrive/Genesis, known as the Nomad. With a library of games dating back seven years, the Nomad was designed to capitalise on gamers who were more concerned with bits than gameplay. It was a gamble that would fail, and the gaming press noted that two to three hours of battery life was even worse than the Game Gear. With the Saturn, Megadrive/Genesis, Game Gear, 32X and Sega CD all on the market at the same time, Sega were unable to provide sufficient resources to support all of this hardware. As a result the Nomad failed to catch on with audiences, who preferred Sega’s earlier handheld over its portable Megadrive/ Genesis.

Despite Sega publicly stating that it “believed the two (Nomad and Game Gear) can co-exist”, it discontinued the Game Gear in Japan in 1996, and worldwide the next year. The Nomad never became a contender, and Nintendo ruled largely unchallenged over handheld gaming until 2004, when Sony released the Playstation Portable (PSP).

Be the first to comment